“There is a sense of the city you can’t plot on a map, or a phone,” Lauren Elkin writes. “It is an intense, embodied relationship to its atmosphere.” Flâneuse is a historical investigation and personal celebration of this relationship, traced through a number of female writers and artists of the city (Virginia Woolf, Jean Rhys, George Sand, Martha Gellhorn, Agnès Varda, Sophie Calle) as well as the urban wanderings of Elkin herself.

“Flâneuse” is the feminine form of the French noun flâneur, meaning “an idler, a dawdling observer, usually found in cities”. This is a definition that Elkin has to make up, as few dictionaries include the word. Flâneur is there, of course, but not flâneuse. Why? Can’t there be a female flâneur? Or, indeed, a woman’s way of observing the urban streetscape that might differ from that of a man? Feminist art historian Griselda Pollock would seem to suggest not: “There is no female equivalent of the quintessential masculine figure, the flâneur: there is not and could not be a female flâneuse,” she declares. This assertive dismissal is what Elkin sets out to challenge. Surely there have always been plenty of women living, and by necessity walking, in cities, and also writing about them. “Once I began to look for the flâneuse,” she states, “I spotted her everywhere. I caught her standing on street corners in New York and coming through doorways in Kyoto, sipping coffee at café tables in Paris, at the foot of a bridge in Venice, or riding the ferry in Hong Kong.”

Of course Pollock was talking about 19th-century Paris. Elkin’s examples of women walking – with the exception of Sand, who cross-dresses as a man to gain access to the Paris streets – all come from the 20th and 21st centuries. Yet I have sympathy with Elkin’s renewed call for recognition of the flâneuse, the female walker and writer of the city. For after a period in the first half of the 20th century, when writers including Rhys, Woolf, Dorothy Richardson and Hope Mirrlees produced masterpieces of what we might describe as literary flâneuserie, it is the perspective of the male flâneur that seems more recently to have reasserted itself. Elkin argues: “The flâneuse is still fighting to be seen: the great writers of the city, the great psychogeographers, the ones that you read about in the Observer on weekends: they are all men, and at any given moment you’ll also find them writing about each other’s work, creating a reified canon of masculine writer-walkers.” Flâneuse offers a counterpart to this recent male canon, reconnecting with the female writer-walkers of the past as Elkin seeks her own freedom in the city.

New York, Paris, London: they all have their flâneuses, their women walking and writing the city. Their urban maps and atmospheres, however, are all different. For Elkin, growing up in the suburbs of Long Island, New York is at once “home” and the city she is trying to escape. “How can you wander on a grid?” she asks. In Paris as a student, she begins her own flânerie in the company of Ernest Hemingway – “I learned from this most unlikely of teachers”, she admits, “until I found Jean Rhys.” Discovering Rhys’ After Leaving Mr Mackenzie at the Shakespeare and Company bookshop is the start of Elkin’s urban Bildungsroman. She is honest about her youthful romanticising of Rhys’ “aesthetics of pain”. To the 20-year-old in Paris, wandering its streets looking for meaning, Rhys’ novels offer “the addictive pleasure of despair”.

Writing my own PhD in London in the late 1990s, I preferred the quiet, lonely independence of Miriam Henderson, the autobiographical protagonist of Richardson’s Pilgrimage, to the jaded glamour of Rhys’ deracinated heroines. Miriam’s London is a city in which life is measured out in the spoons of A. B. C. tea shops rather than the mirrors of continental bars, but her relationship to the city is that same deeply embodied, entrancing one experienced by all of Elkin’s flâneuses: “No one in the world would oust this mighty lover, always receiving her back without words, engulfing and leaving her untouched, liberating and expanding to the whole range of her being.”

Our relationship with cities, Elkin observes, depends on the signals of our own “personal frequency”. London is not Elkin’s city, however much she walks and seeks to build a relationship with it. “I love walking in London,” Woolf’s Clarissa Dalloway declares. Elkin, however, struggles to find the London that gave Woolf so much inspiration, and gets lost in its Bloomsbury squares. London seems to remain for her a 21st-century city. She cannot connect with its past, in contrast with Paris, where she confesses: “I am always looking for ghosts on the boulevards.” Richardson and Woolf are London’s great flâneuses. Elkin follows in their literary footsteps, but Paris is her spiritual home. “Most of the meaningful moments of my life have taken place here,” she writes. “Bliss has unravelled, joy coalesced out of nothing; my life has pulsed in its streets.”

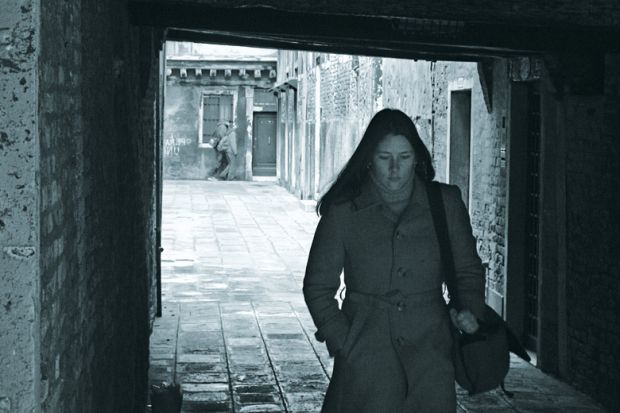

Elkin attempts to walk in other cities, too. In Venice, reading Henry James’ The Wings of the Dove and attempting to write her own novel, she finds that she is a tourist, even if, as she likes to think, “the good kind”. The floating city, she notes, is not one you approach with an itinerary, or try to navigate with map. Bridges multiply, and streets seem to move, or end in water. Tokyo is simply anathema to the flâneuse. “Tokyo is not a walkable city,” Elkin states. “After two weeks, I wanted to scream.” Living on the 16th floor of a business hotel, “the home of the foreigner, the misfit, the impossible-to-assimilate”, she felt trapped in a synthetic imitation of urban life, a city where everything was provided but there was no possibility to roam. Walking is the language by which the flâneur or flâneuse understands the city, and finds the inspiration to narrate its stories. Tokyo is a city that Elkin cannot read, because she cannot learn its language. “To flâneuse in Tokyo I had to walk up staircases, take elevators, climb ladders, to find what I was looking for upstairs, or on rooftops.” A woman in the city perhaps, but can she still be called a flâneuse? Elkin isn’t sure.

What we notice in Elkin’s description of the flâneuse is that she is constantly caught on the border of one place and another: “She is going somewhere, or coming from somewhere; she is saturated with in-betweenness.” It is this moving across boundaries and thresholds that characterises Elkin’s definition of the flâneuse, as dawdling in the city becomes increasingly a means to place oneself, to feel a sense not of possession of the streets but of belonging. “Walking helps me feel at home,” Elkin writes. Her argument is not just about walking, observing and writing the city, but also about our relationship to place, and the feeling and fragility of belonging. After 11 years of loitering in Paris on successive visas, Elkin’s French citizenship is approved. Paris now becomes a city to walk and rediscover anew, as a woman, a flâneuse, who now legitimately belongs. “I’ll spend the rest of my life trying to know Paris from within,” she declares.

Deborah Longworth is head of the department of English literature, University of Birmingham, and author of Streetwalking the Metropolis: Women, the City, and Modernity (2000).

Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice and London

By Lauren Elkin

Chatto & Windus, 336pp, £16.99

ISBN 9780701189020

Published 28 July 2016

The author

Lauren Elkin was born and raised in the suburbs of New York. “It instilled in me an instinctive fearfulness and wariness of the world, which I’m trying to get over,” she admits.

As a child, “I read everything I could get my hands on, from those babysitter stories to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, but hated reading the books we were assigned in school. I remember bringing Anne Rice to English class one day and reading that while everyone else was studying Ivanhoe; the teacher didn’t even say anything to me. I think they didn’t know what to make of a kid whose big act of disobedience was reading.

“My parents were wonderful about it, though; they never made me feel strange or inadequate; they took me to the theatre and to museums and, of course, to the local library and let my imagination take me down whatever roads it desired.”

The flâneuse is an urban explorer; does Elkin ever find herself drawn to more bucolic rambles? “I really don’t have an interest in walking for very long in the country. I’ve just come back from Cornwall, and walking along the River Tiddy there is one of my favourite things to do in the summer – but more than, say, half an hour, and I’m ready to go back.”

In September, she will take up a post as lecturer in the department of English and co-director of the Centre for New and International Writing at the University of Liverpool. “I’m very excited to start spending time in Liverpool. Being from New York, a maritime city, I felt an immediate affinity with it, and I’m planning to take my students on walks along the docks.”

What gives her hope? “Not much at the moment, I’m sorry to say; this has been a terrible summer, after a very difficult past couple of years. But the one thing that keeps me going is the commitment to enjoying everyday life. As long as we can sit on a cafe terrace with a glass of wine and a book, we’ll be fine.”

Karen Shook

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Steps to urban enlightenment

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?