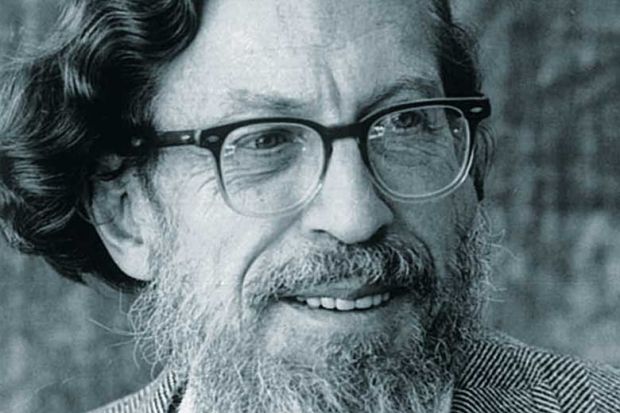

Charles Stein was born in Brooklyn, New York on 22 March 1920 and studied mathematics at the University of Chicago (1940). He worked in the Air Force during the Second World War, analysing how the weather might affect military activity, but, although happy to take part in the fight against fascism, was critical of every single occasion in which the US got involved in subsequent wars.

His convictions soon had an impact on his career. Discharged in 1946, Professor Stein completed a doctorate at Columbia University in 1947 and went to work at the University of California, Berkeley. When the politics of the McCarthy era meant that he was required to sign a loyalty oath, he refused to do so on principle. It was this that led him to make his career at Stanford University, which as a private institution required no such oath. He was appointed an associate professor in 1953, promoted to full professor in 1956 and continued working there until he became emeritus in the late 1980s.

Although never very prolific as a writer, something he attributed to a combination of laziness and perfectionism, Professor Stein was known as “the Einstein of the Statistics Department” and had a deep impact on the whole field (sometimes for work written up by others). His legacy in the field lives on in the names of Stein's method, Stein's lemma and Stein's paradox. The last of these was described by Emmanuel Candès, Barnum-Simons chair in math and statistics at Stanford, as “the most provocative result in our field of statistics in the last 60 years”.

“Many of the people in our department have lived off [his] ideas,” said Susan Holmes, professor of statistics at Stanford. “He was just a genius. He thought outside the box. He didn’t accept things for what they were.”

Alongside his path-breaking professional work, Professor Stein used the protection of his tenured post to speak out on the political causes he believed in. He refused to accept military funding and was the first member of faculty to be arrested for anti-apartheid protests in 1985. Even after retirement, he continued to live on or near campus, to go hiking in the hills and to spend time in the library – partly because a dream had encouraged him to try to use the method he had invented to prove the celebrated prime number theorem. He died in his sleep on 24 November and is survived by a son, two daughters and a grandson.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?