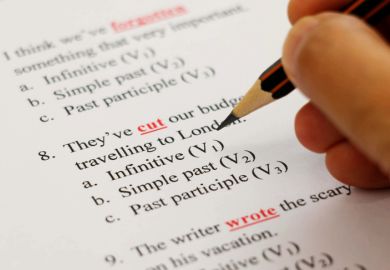

Changes to English language tests, along with an increased use of “unverified” exams, risk doing a “disservice” to students and undermining the “integrity” of the sector, experts have warned.

Amid a government review of English testing provision across universities, results of a recent survey by the Home Office showed that while the vast majority accept “secure” forms of tests, 35 per cent of providers also use in-house testing and 13 per cent accepted letters from recognised employers.

Karen Ottewell, director of academic development and training for international students at the University of Cambridge, said the survey showed discrepancies across the sector in the types of tests being accepted.

“Recruitment and admissions might be in some institutions the bodies responsible for making the decisions with regard to test acceptance, but they’re not the people dealing on the front line with the students when they’re coming in.”

Almost all providers accepted tests from The International English Language Testing System (IELTS) (99 per cent) and Pearson PTE (94 per cent), but others such as City and Guilds were accepted by only 9 per cent.

The Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL), which was accepted by 89 per cent of the 144 providers polled, was recently put up for sale by parent company ETS. The test has faced increased competition in the US from newer competitors such as Duolingo, accepted by a quarter of providers in the survey, and is having to deal with Trump’s crackdown on international students.

TOEFL also recently overhauled its internet based test. “Essentially, it’s like a different version of the Duolingo test,” said Ottewell. “We’re going down a shorter, quicker, cheaper test route with the new TOEFL, which is an interesting choice if they’re looking to sell it.”

Cambridge recently announced that it will not accept TOEFL tests taken by undergraduate students in 2026 and placed it under special measures for graduates.

“We’re not in any way convinced that it’s going to give us the level of insights that the previous version did, and we don’t want to set students up to fail,” added Ottewell.

Luke Harding, professor of applied linguistics at Lancaster University, said larger test providers are increasingly going to have to adapt and adopt different aspects of artificial intelligence to create more efficiencies in their processes.

“I think it is kind of indicative of the changing landscape of English language testing at the moment and we’re probably going to see a lot more of this in the coming years.”

Pamela Baxter, managing director for IELTS at Cambridge University Press and Assessment, said the survey showed a worrying number of universities using less secure and unverified tests.

“This poses a challenge to the integrity of the immigration system: there are ever more cases and growing evidence linking the use of unverified tests to some forms of visa fraud.

“The increased use of poorly regulated tests does a disservice to students using them for university admission: studies show that they are more likely to struggle with coursework and with integration.”

With the government progressing with a “digital-by-default” Home Office English Language Test (HOELT), Baxter said the sector must accept only the most secure forms of language assessment.

Harding said the variety afforded to providers in choosing different tests is a benefit, but the government might be worried by the flexibility on offer.

“I would personally like to see that kept because I think that the diversity is really useful. I think higher education providers have good reasons often for choosing different tests.”

The survey also found that about half of respondents had a written policy in place to help detect and prevent instances of fraud. A small proportion (12 per cent) reported not encountering any instances of fraud, while most were likely to have experienced fraud either rarely, very rarely, or almost never (71 per cent).

Only 16 per cent had no process in place for feeding back on the English language ability of enrolled students, which Ottewell said was “shocking”.

“I’d have thought that’s a duty of care…there should be a feedback loop in this.

“If they do come in with slightly lower levels [of English] for whatever reason…the university has to make sure that there’s support and other things in the institution post-enrolment to make sure the students can upskill and succeed in what they’ve chosen to do.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?