By now, most universities have an artificial intelligence policy. It probably mentions ChatGPT, urges students not to cheat, offers a few examples of “appropriate use” and promises that staff will get guidance and training.

All of that is fine. But it misses the real story.

Walk through a typical UK university today. A prospective student may first encounter you via a targeted digital ad whose audience was defined by an algorithm. They apply through an online system that may already include automated filters and scoring. When they arrive, a chatbot answers their questions at 11pm. Their classes are scheduled by algorithms matching student numbers with lecture theatre availability, and their essays are screened by automated text-matching and, increasingly, other AI-detection tools. Learning analytics dashboards quietly classify them as low, medium or high risk. An early-warning system may nudge a tutor to intervene.

At every step, systems powered by machine learning and automation are making recommendations, structuring choices and sometimes triggering decisions. But it might not be clear to students – or to staff – which parts of this journey are “AI-enabled”, how those systems work, or who is accountable for their outputs.

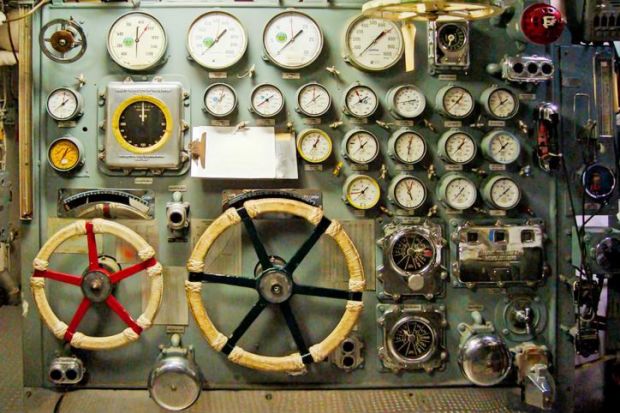

We talk about AI as if it were an app. In reality, it is becoming the operating system of the university.

That shift matters. Apps are optional extras: you download them, try them, delete them. Operating systems are different. They sit under everything else. They determine what can be installed, who has permissions, which processes are possible, and what data is collected along the way. When you change the operating system, you change the whole machine.

As well as student recruitment, learning, assessment and support, AI also touches professional service areas, such as estates planning, financial forecasting and all manner of procurement. Yet our governance is still stuck at the level of “is it OK for students to use ChatGPT in essays?”.

Three uncomfortable truths follow.

First, most institutions do not have a reliable map of their own AI infrastructure. Ask a vice-chancellor, a PVC for education or a chair of council for a single document listing every significant use of AI or automated decision-making across the institution and you are likely to get a polite silence.

Responsibility is fragmented. IT manages some systems. Registry manages others. Teaching and learning committees see bits related to assessment. Data protection officers look at some risk assessments. Procurement teams sign contracts that bake in AI-enabled features nobody has really interrogated. Vendors offer “smart” functions as part of standard upgrades that glide past existing oversight mechanisms.

If you cannot map your AI, you cannot govern it. Universities need a live map of their AI infrastructure: not a glossy digital strategy, but a working inventory of where AI or significant automation is in play, what decisions it shapes, whose data it uses, and which groups are responsible for it. This is basic due diligence, not a nice-to-have.

Second, accountability is fuzzy. When a plagiarism detector produces a spurious match, who is responsible: the software provider, the central team that configured the thresholds, or the academic who is told to “use their judgement” but is under pressure to be consistent? When an analytics system flags a student as “at risk” and nobody contacts them – or flags them falsely and triggers an unnecessary welfare intervention – whose fault was that?

In high-stakes domains such as academic progression, allegations of misconduct or pastoral concerns, universities have legal and regulatory obligations around fairness, due process and equality. It is no longer adequate to shrug and say “the system suggested it”. If we outsource parts of judgement to machines, we need a much sharper understanding of where human responsibility begins and ends.

Governing bodies should insist on clear lines of accountability for any AI system that materially affects students’ progression, classification, or welfare. That means explicit answers to simple questions: Who owns this system? Who can change its parameters? What recourse do students and staff have if it appears to be wrong?

Third, AI is quietly redistributing power and reshaping professional roles. Data and analytics teams, central services and external vendors gain influence. Academic autonomy is constrained by template workflows and automated feedback systems. Students experience judgements that are increasingly mediated by unseen code.

This redistribution is not necessarily bad. Used well, AI can free staff time for higher-order tasks, support more consistent decisions, and surface patterns of inequity that would otherwise remain invisible. But without deliberate design, the risk is of a kind of quiet de-professionalisation: academics become supervisors of automated marking rather than assessors; tutors become implementers of nudges generated elsewhere; professional staff become responsible for outcomes they did not design.

We need cross-cutting oversight, not just scattered committees. A serious AI governance group should bring together academic staff, professional services, students, IT, data protection and equality specialists. Its remit should not be to rubber-stamp tools, but to scrutinise the architecture: how these systems interact, which values and assumptions they encode, and what risks they create.

And we must take student voice seriously on such matters. If a student’s educational experience is being shaped by an invisible operating system, they have a stake in how it is designed.

The AI revolution in higher education will not arrive with humanoid robots giving lectures. It is already here, humming quietly in the background systems that allocate attention, label risk and shape opportunity. The challenge now is making sure someone is actually in charge of the engine room – and that the people whose lives are affected by it know where the controls are.

Tom Smith is the academic director of the Royal Air Force College and an associate professor of international relations at the University of Portsmouth.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?