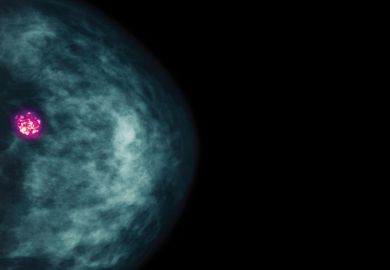

One of the biggest scientific reproducibility studies to date has found that top-rated cancer researchers rarely share their data and that their published conclusions typically fail to replicate.

Federal funders admitted concern over the depth and persistence of the problem exposed by the Virginia-based Center for Open Science (COS), and agreed that they needed to make academic scientists do more about it.

“I don’t think we should accept this as just the way it has to be,” the director of the US National Institutes of Health, Francis Collins, told Times Higher Education. “We’re deeply concerned about this, and aim to keep pushing really hard on it.”

For its appraisal, published in eLife on 7 December, COS aimed to repeat 193 cancer biology experiments described in 53 highly cited journal articles from a decade ago. But it could rerun only 50 experiments from 23 papers, largely because of inadequate data files and a widespread lack of researcher cooperation. Of the 50, the replication efforts overwhelmingly found the reported effects of a tested theory or intervention repeating at magnitudes substantially smaller than levels described in the original articles.

Even if there remains legitimate debate over what size of a finding’s repetition constitutes scientific replication, the obstacles preventing outside scientists from meaningfully checking the published work of their colleagues cannot be accepted, said Michael Lauer, the head of external grant funding at the NIH.

“It is concerning that about a third of scientists were not helpful, and in some cases were beyond not helpful,” Dr Lauer said.

The NIH’s planned responses to reproducibility shortcomings include a broad data-sharing mandate for its grant recipients set to take effect in January 2023, and a coming series of new requirements for greater rigour in tests involving animal subjects.

The implications for universities could mean that the NIH funds fewer medical studies so that those it does support include large enough numbers of test subjects, with enough diversity in their characteristics, and well-structured designs, to provide surer outcomes, Dr Collins told THE.

In the academic research community, he acknowledged, “everybody’s worrying about” what such changes will look like. But “if a study’s worth doing, it’s worth doing right”, said Dr Collins. “That may mean that some studies aren’t really going to be worth doing in terms of what their possible outcomes will be.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Cancer experts slight project on reproducibility

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?