Lecturers with formal teaching qualifications are valued by students far more highly than those who are active researchers, says a major survey that is likely to reopen the debate over the need for compulsory teacher training.

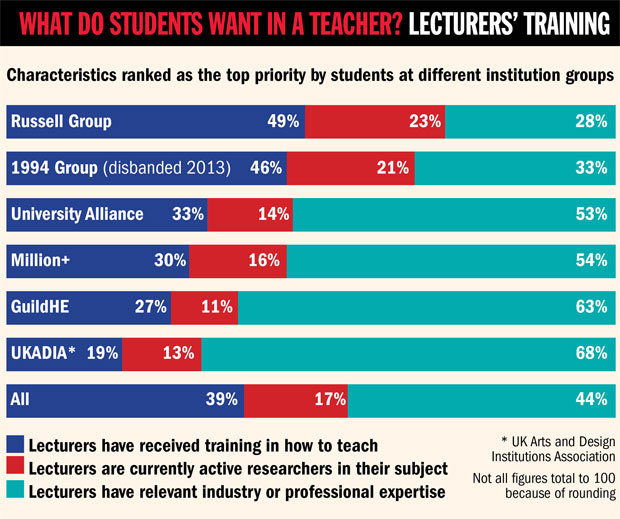

Thirty-nine per cent of the 15,129 respondents in the Higher Education Policy Institute’s UK-wide Student Academic Experience Survey 2015 say that the most important characteristic of a lecturer is that they have some formal training to teach.

Only 17 per cent felt that it was most crucial for staff to be currently involved in research in their discipline, according to the annual survey, a joint project with the Higher Education Academy, published on 4 June.

Meanwhile, the biggest priority for students was for lecturers to have professional or industrial expertise in their field, with 44 per cent saying that this was imperative.

Demand for such vocational knowledge among staff was most acute at post-92 universities. Some 53 per cent of respondents at University Alliance institutions listed it as their top priority for staff, which rose to 54 per cent at Million+ universities and 63 per cent at small and specialist GuildHE members.

However, it is the high support for teacher training identified by the annual report that is likely to intensify pressure on staff to gain some sort of formal accreditation.

Demand for teacher training was strongest at Russell Group universities, where 49 per cent listed this as their most desirable characteristic in staff, as opposed to 23 per cent who most valued having research-active staff in their classrooms.

Those studying physics, maths or computer science, languages and engineering were most keen on having a trained teacher, whereas those doing vocational subjects sought professional expertise in staff.

Nick Hillman, director of Hepi, said that it was difficult for students to understand the benefits of having research-active lecturers.

“Students probably do see the benefit if they are actually involved in some aspect of the research themselves, but otherwise it’s not that clear what they get from this arrangement,” he said.

“They are more likely to want a less experienced postdoc who is interested in them, rather than a professor in their sixties who is writing their latest book,” he added.

David Palfreyman, director of the Oxford Centre for Higher Education Policy Studies, went further and said that universities should admit that there was no evidence to suggest a “magical link” between research and good teaching.

“If there is a wonderful link, how come half of undergraduate teaching is delivered in some places by casual temps who are not paid to be research-active?” he said.

Mr Palfreyman added that there was also nothing wrong with some universities becoming largely teaching-only institutions if they did the “job well”.

But Denise Sweeney, an educational designer at the University of Leicester’s Leicester Learning Institute, said that the immense value of research-active staff was not always communicated to students.

“Any graduate who has to think for a living needs to know how to research, so it’s important that students are taught by scholars who know how to do this,” she said.

The survey’s findings strengthened the case for the inclusion of institutional-level data on teaching qualifications in the Key Information Sets, said Mr Hillman.

Universities are currently required to submit data on how many staff have teaching accreditation, but the information has not yet been published because of a lack of statistics at many institutions.

The Conservatives’ manifesto pledge to introduce a “framework to recognise universities offering the highest teaching quality” may also see renewed interest in teaching qualifications.

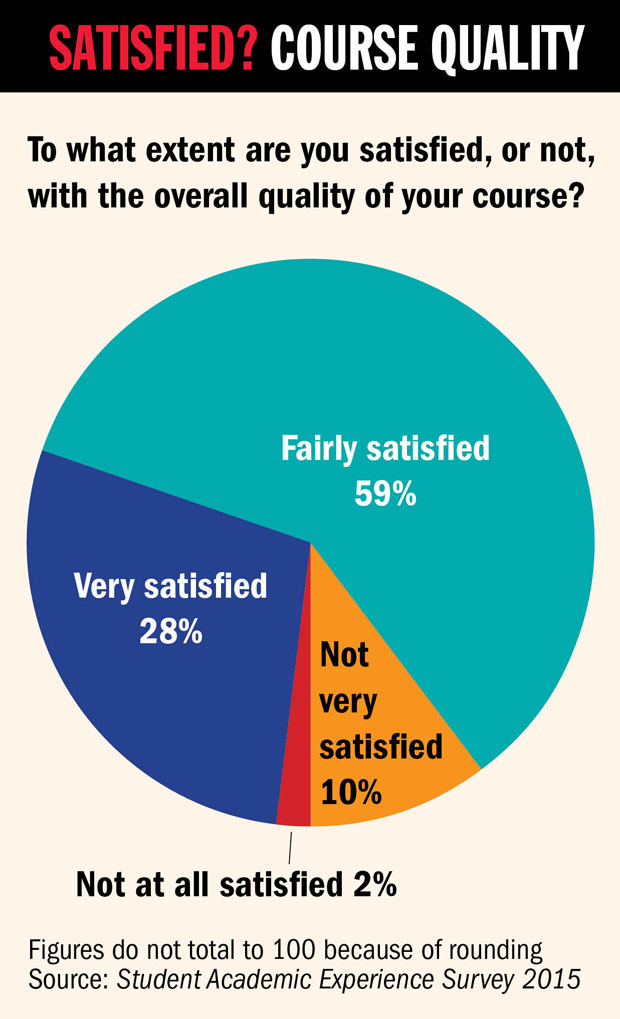

In other findings in the Hepi-HEA report, about a third of students in England (34 per cent) said that they received poor or very poor value for money from their course – which rose to 44 per cent for those with fewer than 10 contact hours a week. Just 6 per cent of students in Scotland – where there are no tuition fees for Scottish students – felt that they received poor value for money.

Students with fewer than 10 contact hours were most likely to say that they wish they had chosen a different course, with 38 per cent reporting this. Business and administrative studies students, alongside architecture and planning undergraduates, are most likely to want to change courses, with 43 per cent stating this aim.

But overall, 87 per cent of students say that they are satisfied with their course and only 12 per cent say it is worse than they expected.

“Students say they are satisfied with their courses in substantial numbers, but when you drill down the answers are very different,” said Mr Hillman. “When you ask them to think [about] what they are getting for their money, they process the question in a different way.”

For the first time, this year’s survey asked about the information provided by institutions to students on how their tuition fees are spent. Just 18 per cent of respondents feel that they have sufficient information on this, whereas 75 per cent say that they do not.

Providing undergraduates with subject-level data on how their tuition fees are spent was an “inevitable consequence of relying so heavily on student loans”, said Mr Hillman, who added that this transparency may also have a useful political purpose.

“Universities are lobbying for increasing fees above £9,000, but until MPs in marginal seats understand where the extra money would go, then they are unlikely to support any rise,” he said.

POSTSCRIPT:

Article originally published as: Student survey puts teaching high on agenda (4 June 2015)

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?