Dozens of Australian universities face having their immigration risk ratings downgraded next month, promising further delays in student visa processing.

Australia’s Department of Home Affairs (DHA) uses a three-level grading system to assess the risk of students breaching visa conditions. People applying for visas to study at universities deemed level 2 or 3 – the higher risk ratings – must supply additional evidence about their English skills and personal finances.

And under Australia’s new migration strategy, their applications are put in the slow lane while requests for visas to study at level 1 universities are processed quickly.

Times Higher Education understands that the number of level 2 universities increased after the former government’s removal of international students’ working restrictions, resulting in an employment-fuelled boom in student visa applications. Students’ working hours remained unlimited for another 13 months after Labor won power in May 2022.

Currently, 17 universities are rated level 2 and one institution is level 3. The ratings are based on factors such as visa cancellations and the proportion of visa applications that are rejected because of fraud or other reasons.

The ratings are due to be updated in March based on statistics collected in 2023 – a period when higher education visa rejection levels spiked to unprecedented levels.

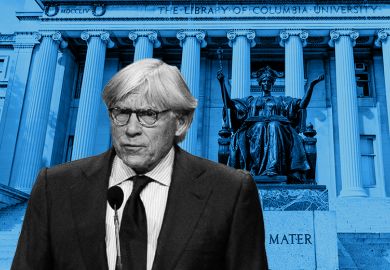

Mike Ferguson, pro vice-chancellor of Charles Sturt University (CSU), said he expected more universities to slip into the level 2 and 3 categories in March and during a subsequent update in September.

“This seems to all be driven by visa refusals,” said Mr Ferguson, a former director of international education policy at the DHA. “It’s not non-compliance or cancellations. It’s visa decision-making, with a very obvious crackdown on key markets like India without requisite transparency.”

The slowdown in visa processing is already costing universities dearly. In a joint letter to home affairs minister Clare O’Neil, 16 vice-chancellors say they faced losses of A$310 million (£160 million) this year due to visa delays and rejections.

CSU vice-chancellor Renée Leon, who was a signatory to the letter, said her institution stood to lose A$20 million because around 60 per cent of its new overseas recruits were still awaiting the outcomes of their visa applications. “Charles Sturt’s prospective international students are unfairly having their study plans delayed by the government through no fault of their own,” she said.

A DHA spokeswoman said all student visa applications were assessed on the “merits of the individual cases” against requirements prescribed in legislation and eligibility criteria detailed on the department’s website.

Experts disagreed. Abul Rizvi, a former deputy secretary of the department, said he believed the government’s response to damaging headlines over soaring temporary resident numbers had been to “crank up the refusal rate for students”.

Another source, who asked not to be named for fear of reprisal, said this was unacceptable. “There are more and more really perplexing rejections. Institutions have invested in much stronger vetting systems, like video interviews with every single applicant, and students that they have a lot of confidence in are still being knocked back,” they said.

“When you’re withdrawing applications en masse because the students are from a particular country, that is a failed system. Frankly, we’d prefer caps. We’d rather have something transparent that we can plan around than the current scenario.”

Universities say their risk ratings are also being downgraded for other reasons beyond their control – for example, poaching of their students by cheaper vocational colleges. As well as losing revenue, the universities carry the blame if the students fail to obtain fresh visas.

A parliamentary committee found last year that poaching was rife, encouraged by lax regulatory oversight.

Mr Ferguson said the government had “put fuel on the fire” by allowing students to work unlimited hours and boosting their employment rights after graduation.

“I don’t know anybody in the sector who wanted unlimited work rights or some of the other changes,” he said. “Government created this mess and foisted it upon universities, taking a drunken sailor-like approach to visa policy and processing by swinging from one extreme to the other, with genuine students caught up as collateral damage.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?