Further education colleges have won 9,547 of a 20,000-strong pool of undergraduate places reserved for institutions charging tuition fees of less than £7,500 a year, it emerged this month.

The auction forms part of the government's attempt to encourage competition from alternative, cheaper providers, and the final allocations are to be published shortly after an appeals process.

But beneath colleges' apparent success, the reforms are changing their relationships with universities.

Since the 1990s, colleges offering higher education have been dependent on universities to allocate them funded places and validate their degrees. Although the relationship has never been an equal one, this has not stopped them working together to offer higher education in far more locations than universities could manage by acting alone.

However, a long-established spirit of collaboration is being shaken by the competition being inculcated across the sector in England.

Colleges fear that they are now at the mercy of universities that are withdrawing places and validation to protect their own student numbers or their reputations. Despite the promise in last summer's White Paper that they would provide more higher education, further education colleges may not benefit nearly as much as hoped when they compete with formerly benevolent masters.

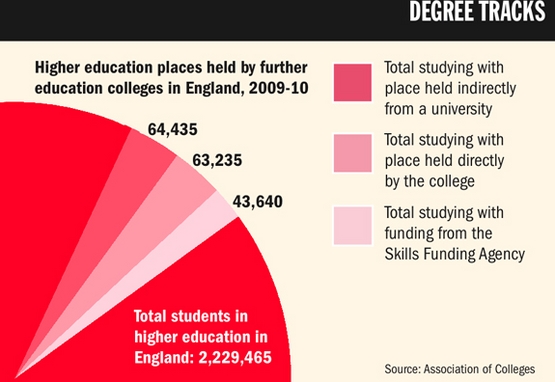

Currently more than 170,000 students study higher education at over 250 further education colleges in England, accounting for 7.7 per cent of all higher education places (see chart below).

Excluding those places paid for by employers or skills funding agencies - which should not be as affected by the reforms - slightly over half of these students are funded indirectly. In these cases, a university is granted the place by the Higher Education Funding Council for England and then passes most of the money to a partner college, which does the teaching.

The other half are funded directly, with colleges receiving their money from the funding council. But colleges still require a university to validate the degree, for a fee.

Under the White Paper's "core and margin" system, universities and colleges compete for a significant portion of student places. For 2012-13, the basic allocations of universities and directly funded colleges have been cut by 8 per cent to create the pool of 20,000 places.

Nick Davy, higher education policy manager for the Association of Colleges, said the extra 9,547 places will increase new degree-level entrant numbers to further education colleges by about a quarter. "However, this figure is brought down substantially by the practice of universities withdrawing indirect student numbers from the sector," he said.

Because of this, Mr Davy estimates that the number of places in further education will grow by just 7 per cent in 2012, "a long way from the government's intention to significantly support degree-level growth in the college sector".

'Looking for other partners'

James Winter, head of the Council of Validating Universities, said that because many universities expect to struggle to keep their "financial heads above water" under the new funding regime, some have withdrawn indirectly funded places from colleges to make up for the loss of the 8 per cent margin.

"Some [colleges] are being dropped by the universities completely and are looking for other partners," he said.

In an online survey conducted by the AoC in November, 11 colleges out of 50 said that their indirectly funded places were being cut by more than 20 per cent in 2012.

Another 11 said that their numbers were being reduced by a smaller amount, 16 reported no cuts at all, and 12 were still in negotiations with their partner university.

For 2013, 14 per cent of colleges said that partner universities were planning to withdraw their places altogether.

Colleges with directly funded places are not vulnerable to universities clawing back their places in the same way, but they have been angered by Hefce's decision not to exempt them from the 8 per cent cut as was first proposed. In mitigation, each college's first 50 places have been protected and they have been allowed to bid for places from the 20,000 pool.

Mr Davy called the decision "plain daft" because colleges have had to put in bids to get the 8 per cent back.

Mr Winter added that the cut of 8 per cent will hurt colleges more than universities because they have smaller economies of scale. "If you have only 100 to 200 (higher education students) in your college, 8 per cent is a big difference," he said.

Of the 167 colleges that bid for places, 143 have been successful. This means that unless other colleges are given some of the 1,150 places still up for grabs in an appeals process to be completed at the end of the month, 24 will miss out altogether.

Another problem facing directly funded colleges is that because universities are now more conscious of their brands, many of them will wonder whether allowing students to earn their degrees in outside colleges dilutes the value of their awards.

Some universities "want to make their brand so distinctive that they want to restrict it", Mr Winter said, although he did not think that prospective applicants would mind, or even realise, that an institution's degree was offered elsewhere.

Mr Davy also said that some universities were pulling out of validation because of fears over the value of their brands, although he said they were in a minority.

Both Mr Davy and Mr Winter, representing colleges and universities respectively, said the government's approach was damaging and muddled.

The competitive system is "nonsensical", Mr Davy observed, because colleges are dependent on their competitors - universities - if they want to offer higher education.

"You have got a competitor who is controlling your product development," he said.

Mr Winter added that the plans have "absolutely not" been properly thought through. He said the new policies are "unfortunately causing dreadful damage to the relationship between universities and further education colleges, which ought to be symbiotic".

Vince Cable, the Liberal Democrat business secretary, told the AoC's annual conference in November that he had warned vice-chancellors that clawing back franchised places was "anti-competitive behaviour" that was "simply unacceptable".

But Mr Winter said this meant that universities were "being told off for behaving like it's a free market" when that was exactly what the coalition was trying to encourage.

He added that he did not believe vice-chancellors would heed Mr Cable's admonition because "universities will do whatever they need to survive financially".

david.matthews@tsleducation.com

So long Lincoln, hello autonomy: Boston College replaces lost places, and then some

Last year, the University of Lincoln withdrew about 50 part-time places from Boston College, citing uncertainty over its own student numbers in the new tuition-fee regime.

Amanda Mosek, principal of Boston College, said she thought the decision was "short-sighted" and warned that with applicant numbers falling, Lincoln "may well need us in the future".

To counteract this loss, Boston put in a bid for 96 of the 20,000 margin places on offer.

It won 54 full-time places for higher education students. This was an outcome that the college was "really pleased" with, said Fiona Grady, vice-principal (curriculum and quality). The allocation allows it to run five courses that it would otherwise not have been able to offer.

For example, the college can continue a computing course that uses places from the University of Sunderland, in an arrangement that is coming to an end.

As Boston's places had all been held indirectly, the margin places give it much more autonomy, Ms Grady said.

"It would have been nice to have 96, but now we have our own places."

Ms Mosek said that she was pleased "that the government recognised [in the White Paper] that colleges can offer higher education".

"There's a lot of snobbery from universities," she said.

"People who live in Boston have very limited opportunities to study higher education. Generally [we cater for] a different type of student, who thinks that trekking off to Lincoln is a huge distance away."

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?