As more hard-working high-flyers are rewarded with titles, there are fears that the boost in numbers may devalue the honour. Tony Tysome reports

A rapid rise in the number of professors in UK higher education over the past decade is a reflection of growing competition in the sector, more accountability, changing priorities and greater expectations among the younger generation of academics.

So say university managers, human resources executives, professors, academics and higher education experts, who were asked to comment on figures illustrating the trend supplied to The Times Higher by the Higher Education Statistics Agency.

All agree that what it is to be a professor and what it takes to become one has changed significantly in recent years, and that this offers both new opportunities and fresh challenges for aspiring professors and people who already have the title.

Most feel that professional standards have risen, so that academics are expected to have achieved more before gaining a professorship. There is also the feeling that they are required to do more once they have secured the position.

But there are concerns that, with the total number of professors in the sector approaching 16,000, there is a danger of "grade inflation" taking place so that the title could begin to lose its value as a mark of academic excellence and leadership.

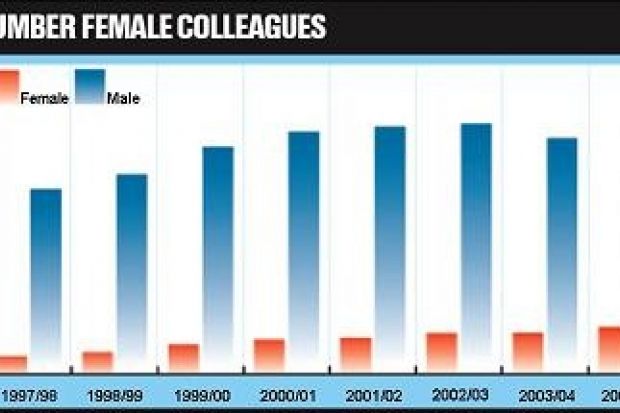

The fact that only 17 per cent of professors are women and 13 per cent are black or from minority ethnic groups is also a cause for concern, even though progress is being made each year to improve equality and make the academic workforce more representative at senior levels.

According to Val Walshe, personnel director at Lancaster University, many institutions such as Lancaster are in the process of tackling equality issues by demystifying the pathway to promotion and revising and clarifying professorial rates of pay.

She said: "It's partly about providing encouragement for people who are already in the institution, and also about signalling what we have to offer to people who might be thinking about coming here."

Mike Smith is pro vice-chancellor for research at Sheffield Hallam University, which is reviewing its criteria for professorial appointments.

He said that his experience of sitting on appointments committees in three different institutions over the past ten years convinced him that it was the research assessment exercise that has had the biggest impact on higher education culture, which in turn had led to the rise in the number of professors.

He said: "When I was recruited to a chair in 1989, it was a different world. I would say that the RAE has been responsible for the biggest changes since then, and that this is so closely related to the increase in the number of professors that it is difficult to disentangle the two."

Peter Marsh, deputy vice-chancellor at Bolton University, said the criteria for becoming a professor had broadened to reflect the changing nature of institutional missions.

Rather than focusing purely on research and teaching, institutions are ready to offer professorships to academics who can demonstrate excellence in knowledge transfer, engagement with business and the community, or curriculum development. But this has thrown up new challenges as well as opportunities for academics.

He said: "Although you can still define the archetypal professor who concentrates almost 100 per cent on research, in general, the position is becoming more complex and involves more engagement with the outside world and in team leadership.

"While in the past academics could define their role as either teaching or research, increasingly they are expected to take on multi-faceted roles and to decide which of these broader responsibilities they are going to specialise in."

Alan Smithers, director of the Centre for Education and Employment Research at Buckingham University, said the proliferation of professors was partly a result of institutions awarding more honorary and visiting professorships.

He said: "One often comes across someone who is regularly using the title but who is not actually employed by a university.

"A number of people exploit this, and universities seem to go along with it because with the RAE they are driven to mark themselves out as leading research institutions, and one of the ways they can do that is by increasing the number of professors they have."

Professor Smithers said that in the UK the sector appeared to be moving in the direction of the North American system, where most academics have at least an associate professor title.

He said: "It will be interesting to see how academics distinguish themselves in future, as more and more become professors. We could even end up in a position where certain people, particularly those with roles in the professions, start to drop the title because it has become so common.

"It could mean that the title of doctor is seen in future as a better signifier that you have conducted original research."

A spokesman for Warwick University, which last year adopted the US system so that all its academics can call themselves associate professor or professor, said that closer collaboration with North American institutions was behind the move.

"There is a lack of understanding of our titles and the UK system in North America. So we wanted to give our academics the option of using the title of professor so that their position was understood," he said.

Despite concerns about possible grade inflation, Ron Barnett, professor of higher education at the Institute of Education, said there was no doubt that standards had risen dramatically in what academics needed to do to gain a professorship.

He said: "What we expect of professors today has not only increased but also widened.

"It has gone beyond simply gaining grants and getting papers published. People must demonstrate that they perform well in teaching, academic leadership and various aspects of administration. "It is also important to institutions to ensure that academics achieve these high standards because, if they are going to survive and flourish, they need a great deal of human capital. The title of professor is still a strong signifier that one has that capital to offer."

These changes added up to a more dynamic career structure for academics, one that offered greater rewards more rapidly to those who were prepared to accept more roles and responsibilities, he added.

"The days of having to wait to step into the dead man's shoes are gone. What that means is that it is possible now to rise through the ranks much more quickly, even though what is expected of you is much more intensive," Professor Barnett said.

tony.tysome@thes.co.uk </a>

Stay focused on the goal

* As a newly appointed professor of interprofessional education at Sheffield Hallam University, Frances Gordon is still excited about gaining the position - particularly since she feels women face more of a challenge in getting there.

"I am encouraged by the increasing number of women professors because it is not easy for a woman to scale the ladder, especially if she is a working mother," she said. "I would say to women academics who have children that, yes, it can take longer to become a professor, but don't ever give up and write off everything that you can achieve."

* Andrew Cooper gave little thought to the significance of becoming a professor of chemistry at Liverpool University - even though he managed it at the age of 33.

He said: "My view has always been that you just have to focus on the job, even though it is pretty clear now that there are opportunities to get promoted much earlier than had been the case in the past.

"My view is that internationally, the system in the UK is poorly understood. So worrying about grade inflation is a bit of an inward-looking thing."

* The main driver behind the rising number of professors is growing competition between institutions, according to Anna Siewierska, professor of linguistics at Lancaster University.

She said: "Young academics are much more career conscious and want a better idea of what possibilities are in front of them. They are also much more ready to change institutions if they are not happy. Institutions have reacted by providing a more transparent career path, which has made it easier for people to progress."

But women can still be disadvantaged, she said. "Because of their natural predisposition to be more person-sensitive, they often take on roles that are necessary but do not get so much recognition in academia."

* Lynne Sneddon, a 33-year-old lecturer in animal behaviour and psychology at Liverpool University, sees the prospect of becoming a professor as a desirable and realisable goal.

"You get so much more respect in the scientific community if you have the title; and since it is such a competitive career, gaining a professorship is still big news," she said.

"The fact that there are now many more professors is good for young people because it means there are more chances of realising that ambition. Many researchers are going to Europe and the US, so institutions are having to make extra efforts to keep people here."

* The appointment of professors in the UK is moving towards the less exclusive American model, argues David Rudd, who is soon to be promoted from senior lecturer to professor of English literature at Bolton University.

He said: "I am excited about becoming a professor, although there has been a change in what it means to have that position. It has become less exclusive, but I am not turning my nose up at it."nTina Overton, who became professor of chemistry at Hull University last November, believes that the research assessment exercise has had a "massive impact" on the number of professors in the sector.

She said: "It is driving academic practice and staff to do more research, turn out more publications and bring in more funding. In other words, it's pushing them to hit the right buttons to be promoted to a chair.

"I think it's important to protect a certain amount of exclusivity," she added. "It clearly defines people in an institution who have a certain reputation or have achieved a certain level of excellence, and it marks them out as academic leaders."

'I Proved I had the credentials'

Jane Ireland thought she had taken on a tough challenge when she decided to set herself a ten-year deadline for becoming a professor.

But seven years after gaining her PhD, she found herself being offered the position by three different institutions.

As a chartered forensic psychologist, she was happy to accept a professorship at the University of Central Lancashire on a part-time contract. But, despite her quick rise and turning down the offers from Liverpool John Moores and Liverpool Hope universities, she did not feel it had been an easy ride.

She said: "According to some institutions, although I had a strong CV I was at a disadvantage as a young woman. I felt I had to prove myself beyond what the older male applicants had to offer."

Professor Ireland, 33, said she was concerned that an increase in the number of visiting professors and moves towards American-style academic titles could degrade the value of the title.

She added: "Sometimes you find people who do not even have a PhD who are calling themselves professor. I think that is potentially problematic, and universities need to tighten up on it."

But she added that, generally, she felt that standards required to gain a professorship had risen. She said: "It always seemed to me that you had to publish at least one paper a month if you were going to stand a chance of becoming a professor."

"If people are prepared to put in the work, then there are more opportunities to become a professor," she added. "But you really have to prove you have the right credentials for the job - and you can't just sit back once you've got it.

"In the past, it was possible for people to sit on their laurels once they got a chair. But, with the introduction of the RAE, that has changed."

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?