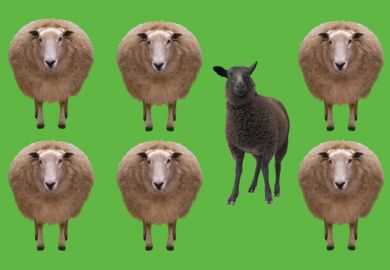

“Bad science” spreads through universities in a process similar to Darwinian natural selection, a paper has argued.

It coins the phrase “the natural selection of bad science”, whereby laboratories that use potentially shaky methods that lead to lots of publication produce successful graduate students who spread these methods when they themselves open new labs.

“Laboratory methods can propagate either directly, through the production of graduate students who go on to start their own labs, or indirectly, through prestige-biased adoption by researchers in other labs,” the paper argues.

“Methods which are associated with greater success in academic careers will, other things being equal, tend to spread.”

A “replication crisis” in science, in which researchers are not able to reproduce others’ results, has been blamed on a number of types of “bad science”, including a reluctance to double-check findings and statistical manipulations to get a publishable result.

This latest paper focuses on the problem of statistically underpowered studies: using too few subjects in an experiment for the results to be reliable.

It found that statistical power in the social and behavioural sciences has not improved since the first warnings of underpowered experiments in the early 1960s.

“Statistical power is quite low”, found "The natural selection of bad science", published in Royal Society Open Science, and “more importantly, statistical power shows no sign of increase over six decades”.

“The data are far from a complete picture of any given field or of the social and behavioural sciences more generally, but they help explain why false discoveries appear to be common,” it says.

Last year, an attempt to reproduce 100 prominent psychology papers found that only about a third managed to replicate statistically significant results.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?