UK universities’ £20 billion China dilemma

Li Ming’s parents made him an offer last month: skip that £35,000 MBA at a UK business school he’s set his heart on and they’d put the money toward an apartment deposit in Beijing instead.

The 26-year-old finance graduate from Shanghai isn’t alone in taking such an offer seriously. Across China’s middle-class households, conversations about overseas education now end with the same question: Is it really worth it?

For universities in the UK and elsewhere in the anglophone world, their answer matters more than ever. International students have propped up British higher education for two decades by paying premium prices – typically two or three times what domestic students pay. That market has been particularly important during the long years during which domestic fees and government grants (in Scotland) have been losing value: Chinese students contribute an estimated £20 billion annually.

Chinese students account for over 30 per cent of all international enrolments to UK universities, and significant numbers of those students attend business schools – whose high fees and relatively low teaching costs often lead them to be labelled “cash cows” for their parent universities. But China’s property market, where middle-class families park 70 per cent of their wealth, remains in crisis, provoking a reconsideration of priorities.

Sending a child abroad for a master’s degree now requires families to move money out of property when prices are at their lowest – or else refrain from investing in such a buyers’ market. And families are increasingly wary of such a trade-off.

Moreover, there is an increasing realisation in China that Western business training is not a perfect fit for Chinese business culture. A new study, of which we are co-authors, suggests that UK business schools’ product might be more attractive to Chinese students and employers if offered in smaller doses.

A department head in Shanghai’s financial district described the sweet spot for Chinese firms: “We maintain strategic connections with international networks while respecting our cultural foundations. We successfully integrated Western project management techniques with our traditional relationship-based approach, creating a hybrid model that works better than either system alone.”

But achieving this balance doesn’t require the firm – or its employees – to splash out £35,000 on a Western MBA. Short-term executive programmes, selective partnerships, or even strategic hiring of Western-educated managers might deliver firms the same benefits at a fraction of the cost. And surveys and industry reports show that firms and families increasingly recognise this.

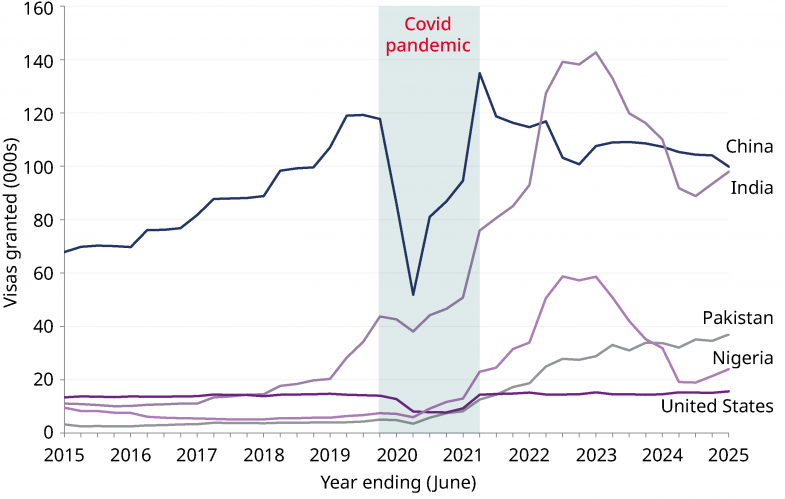

Sponsored study visas granted to the top five nationalities (main applicants), year ending June 2015 to year ending June 2025

Chinese organisational culture acts as a natural filter, dampening the benefits of Western training. Organisations with strong collective orientation – the norm in China – tend to be more selective about which Western practices they adopt. This does not mean change in Chinese companies requires unanimous agreement, but consensus-building is the dominant mechanism.

“When introducing new practices from my UK experience, I learned to engage the entire team in the adaptation process,” explained a Beijing department head who gained Western exposure through a shorter overseas programme, rather than a full MBA. “This collective approach takes longer, but it results in more sustainable change because everyone feels ownership.”

We also identified a surprising twist: Chinese organisations with the strongest ability to absorb and analyse new knowledge – and the greatest willingness to fund full overseas MBAs – are sometimes held back by it as they attempt to integrate too many complex imported practices at once.

“When systems become overly sophisticated, over-analysis can kill momentum,” admitted an HR director at a major state-owned enterprise. “We spent six months adapting a feedback system I learned in the UK, but by the time it was ready, most of its innovative edge had disappeared.”

Then there is the political factor. As US-Chinese strategic competition intensifies – what some call Cold War II – Chinese authorities increasingly scrutinise students returning from the West, concerned about ideological influence. Meanwhile, Western governments worry about technology transfer and intellectual property. In this environment, Chinese families must weigh not just financial returns but political risks; a UK MBA that once opened doors might now invite unwanted scrutiny.

For Western universities, the implications are stark. They need Chinese families to keep paying premium prices for full-degree programmes in order to survive, but Chinese students’ increasing sophistication about calculating the return on investment means that in the long term, the value proposition needs fundamental rethinking.

If the Chinese market comes to accept that moderate exposure to Western education works better than intensive programmes, why charge £35,000 for a one-year MBA when a £10,000 executive certificate – perhaps delivered closer to home, via transnational education (TNE) – might be much more popular?

Some universities are already exploring partnerships in China, offering blended TNE programmes and developing shorter, more targeted courses. The trouble is, of course, that these courses generate far less revenue than full-degree programmes do.

If you’re a UK university administrator, here’s your nightmare scenario: your best customers are discovering they need less of your product to get better results – just as you need them to buy more to survive.

If you’re a Chinese parent, here’s your calculation: a £35,000 MBA might deliver £40,000 worth of value – but only if your child’s future employer uses exactly the right dose of that learning. Career advancement in China is closely tied to organisational evaluation and internal deployment of skills, not simply possession of a credential, so if a firm does not deploy MBA-derived knowledge – or if it does so, only to find that this over-complicates its operations, the MBA holder should not expect that lucrative pay rise they always envisaged.

But while the return-on-investment in an MBA may be unclear, an apartment deposit delivers 100 per cent of its value immediately, even – or perhaps especially – in a depressed market. And for families like Li Ming’s, that is a compelling proposition.

Li Ming has not yet decided whether to accept his parents’ offer, but many like him surely will. As priorities shift, the two-decade-long education partnership between China and the UK faces its most serious test yet. If our research is any guide, its survival in its current form is open to considerable doubt.

Jie Wu is chair professor of strategy and entrepreneurship at the University of Aberdeen. Peng Zhou is professor of economics, university dean of international and Confucius Institute director at Cardiff University.

Chinese business schools’ global challenge

For two decades, the MBA and the executive MBA served as golden tickets for ambitious Chinese professionals reaching for the next rung on the corporate ladder. And a certificate from the most prestigious business schools in China or overseas was a passport to the upper floors of corporate towers, conferring social capital, access to international networks and proof of global vision.

But the ticket’s lustre has somewhat faded in recent years. In common with elsewhere in the world, business education is facing a crisis of confidence in China. Tuition fees keep climbing, while the return on investment is slipping.

According to the Ministry of Education, more than 12 million graduates – another record high – walked out the gates of Chinese universities in 2025. But China’s economy is continuing to face headwinds as it undergoes structural transformation, and its job market is feeling the squeeze. Adding another 12 million jobseekers will potentially compound an already high youth unemployment rate, officially recorded at 17.7 per cent in September 2025.

For business graduates in particular, sectors once viewed as safe havens, such as finance and consulting, are shrinking or facing disruption from AI and automation. In such an environment, young professionals are rightly asking the blunt question: is business school still worth it?

Gary Dushnitsky, deputy dean at London Business School, put it succinctly at the 2025 Global Business Education Deans’ Forum and Expo, held in October at Fudan University in Shanghai. “Students today are very mindful of the return on investment in business education,” he said.

And what is that return? Business schools are struggling to stay relevant as technology and international politics quickly evolves. The once-dominant case-study method – dissecting yesterday’s corporate successes – feels increasingly static in a world of constant disruption. It is becoming increasingly clear that the business classroom of tomorrow cannot solely be about analysing the past: it must also be about co-creating the future.

Professors and students are starting to embrace AI and data analytics to simulate the business world as it evolves, but such a shift demands more than digital literacy: it requires a mindset of enquiry and experimentation, in which students learn to question assumptions and make judgements rather than just memorise conclusions.

Yet the challenge runs deeper than pedagogy. The very foundation of globalisation – long the lifeblood of business education – is shaking. For decades, cross-border programmes, dual degrees and international cohorts allowed students to think and act across cultures and markets. But tightening visa regimes and restricted research exchanges, amid rising geopolitical tensions, have curtailed institutional partnerships and narrowed students’ horizons.

The “invisible hand” of the market is yielding to the visible hand of politics and national security. Concepts once taken for granted in business classrooms – open collaboration, global synergy, win-win cooperation – are being throttled as trade controls, technology bans and shifting alliances redraw the world’s commercial map.

The question facing business schools today, then, is profound: does the “universal logic” of business still hold? And if it doesn’t, how must they adapt?

For Chinese business schools, the old version of internationalisation – English-language courses, imported cases, short-term exchanges – is no longer enough. The next phase should be about shaping perspectives that connect China and the world: business academics should move beyond merely introducing models from abroad to sharing China’s experience and expertise with global audiences.

Moreover, China’s broad economic shift offers new avenues for innovation in business school curricula. Green development, digital economy, regional revitalisation and industrial upgrading all demand leaders who can navigate complexity and drive sustainable change. Business schools that partner closely with enterprises and local governments have the opportunity to shape this next phase of China’s growth.

But the goal of education is never merely to prepare students for a job. It is also to help them contextualise their role in a changing world, to cultivate the ability for lifelong learning, and to guide them to think beyond themselves. For business schools, that means teaching students to balance algorithms with ethics, efficiency with empathy, tech worship with critical thinking, and global vision with local responsibility.

The father of management education, Peter Drucker, once warned: “The greatest danger in times of turbulence is not the turbulence; it is to act with yesterday’s logic.” For China’s business education, that warning has never resonated more deeply.

Only when business schools evolve from disseminators of knowledge to co-creators of value can they reclaim their relevance – and their place on a fractured global map.

Ni Tao is a journalist and communication specialist and adjunct lecturer at the School of Journalism, Fudan University.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?