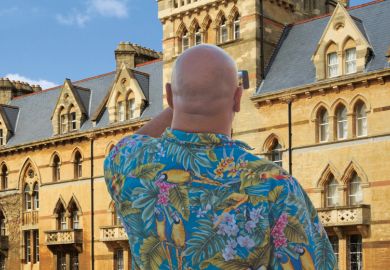

A university without its students is, for the visitor at least, a bit of a strange place – an impressive stage, but most of the cast are missing.

These moments of emptiness/peace and quiet (delete as appropriate) are, however, increasingly rare, with campuses no longer offering staff much summer respite.

Instead, they’re likely to be bustling with builders knocking up new student blocks, pasty-faced office dwellers using the conferencing facilities, and – in many cases – overseas students attending lucrative summer schools.

In our features pages, we ask academics and administrators for their take on campus life in August – a time when universities can resemble “a cross between a theme park, an urban warfare training centre and a cement works”.

There’s a reason universities are sweating their campuses so hard: the summer months can be major contributors to the bottom line.

And while they may primarily cater for a wealthy clientele, summer schools can also be a form of international outreach at a time when universities have been shaken by the Brexit vote.

As Sir Leszek Borysiewicz, the vice-chancellor of the University of Cambridge, puts it on his institution’s website, “in this changing world, it is crucial that we retain and nurture a lifelong ability to interact within an international community, and to challenge our own perspectives. That is exactly what we do in our International Summer Programmes, where students of all ages and from all backgrounds study together.”

The same sentiments apply to the international students on full degree programmes, and as well as having Brexit to contend with, universities now have their erstwhile nemesis, Theresa May, as prime minister.

An unanswered question about May’s premiership is whether she will continue on the path she pursued so bullishly as home secretary, viewing the inflow of overseas students not as a triumph to be protected but as a battleground in her drive to cut migration.

The signs aren’t good: although vague about timings, May has repeated her view that net migration should be cut to the tens of thousands, something that’s impossible without either removing students from the figures (which she won’t do) or significantly reducing the number who come to the UK.

In this context, the announcement that a new scheme easing student visa rules will be trialled at just four universities – Cambridge, Oxford, Imperial and Bath – will be viewed with suspicion. They were chosen because of their low visa-refusal rates, but there’s no escaping the fact that at least three of them are precisely the institutions that cynics would expect to be favoured by an Oxford-educated Conservative prime minister.

May has made great play of her desire to govern not for the elite but for all, and broadening the range of universities involved in the two-year pilot would be one way of supporting the institutions that work most with students who are the first in their family to benefit from higher education.

It’s not just about money – mixing with overseas students is even more important for someone whose horizons have been limited by their background, giving them a chance to develop the outlook that Brexiteers claim will be the hallmark of a globally facing Britain.

Our universities are, in 2016, as defined by their internationalism as almost anything else – and that’s as true outside the highly selective research elite as in it.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Summer’s long shadows

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?