The ongoing strike by UK university lecturers was given a major boost recently by students who, according to newspaper reports, brought plates of cakes and biscuits to the dons on the picket lines. A pleasing gesture of solidarity, one might think – although one can’t help wondering whether any of those on the picket lines were able to offer properly personal thanks to their gallant donors. Did they, for example, know any of their names or any of the courses they might be studying?

What prompts such questions is the uneasy but solid evidence that many university lecturers are increasingly ready in this post-pandemic world to risk the wrath of students, vice-chancellors and education secretary Nadhim Zawahi alike by refusing to indulge in face-to-face teaching. Why confront the hazards of travelling all the way to work and allowing a bunch of relatively unkempt and possibly unhealthy students to invade your personal space when you can stay comfortably in your own book-laden home and enjoy the hygienic safety and push-key control over proceedings afforded by a Zoom encounter?

It is not an altogether surprising development. In my long years of university life, I came across numerous disturbing examples of the extremes to which academics will go to avoid any corporeal contact with those they seek to instruct. I vividly remember the distinguished psychology professor who lectured on short-term memory at my undergraduate university. During his introductory remarks, he was bent so low down that his brow and hairline were only just visible to those in the back rows of the auditorium. But as he slowly developed the distinction between short-term and working memory, he began to sink like a collapsing soufflé, until the only element of his presence that remained was a muffled sound emanating from several feet below the lectern.

Other examples are less dramatic. They include the lecturer in social anthropology who had astutely equipped her tutorial office with a swivel chair. This allowed her to conduct her seminars on the libertarian proclivities of the Samoan islanders while simultaneously observing the mating patterns of the Alaskan geese on the university’s artificial lake.

If one was forced to face real living students in a lecture hall, then getting away from them as soon as possible was at a premium. We used to speak with some admiration of the professor of English who would bring his lectures on Chaucer to a sudden end with a hanging question – “And what was so very hypocritical about the good wife of Bath?” – so that he could effect an escape to the senior common room sandwiches and coffee before any his students realised he wasn’t expecting an answer.

Not that avoiding the sight, sound or smell of real students was confined to lectures or seminars. For although the corridors in my university building were relatively narrow, actual physical contact with passing students was regularly avoided by a series of physical evasions that would have gladdened the heart of a blindside flanker.

I vividly recall an excellent student, Julie, whose developing loss of sight had secured her a guide dog. I wondered how she was coping. “Fine,” she said. “All of sudden, lecturers who would normally ignore me now stop for a chat. But not with me – with my dog. ‘Who’s a good girl, then?’ Are you pleased to see me? Yes, you are.’” (Julie told me in strict confidence that she disliked dogs generally, and hers in particular.)

Matters seem unlikely to improve. Avoiding the sight and sound of real students bestows an ever-increasing range of benefits. In these sensitive interpersonal times, Zoom absolves tutors from any possible charges of sexual impropriety and totally removes the imminent threat of a colleague conducting a peer assessment of your teaching in an actual face-to-face seminar.

Not that everyone is available for a Zoom meeting. Only last week a theology lecturer admitted to his class that he was unable to know the full details of the Holy Family’s involvement in the Nativity. “Sadly,” he said, “there was no Zoom at the inn.”

Laurie Taylor is a broadcaster and wrote the weekly Poppletonian column for Times Higher Education for more than 30 years. He is former professor of sociology at the University of York.

POSTSCRIPT:

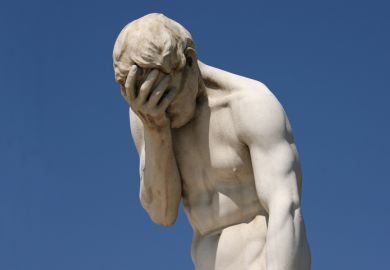

Print headline: Is that a student? Hide!

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?