Probing by England’s universities regulator about Chinese students on government scholarships has left vice-chancellors unsettled, with some believing the Office for Students (OfS) is overstepping its role.

Times Higher Education understands that Arif Ahmed, director for freedom of speech and academic freedom at the OfS, has been approaching the heads of universities that accept students funded by Chinese government scholarships and questioning them about these partnerships.

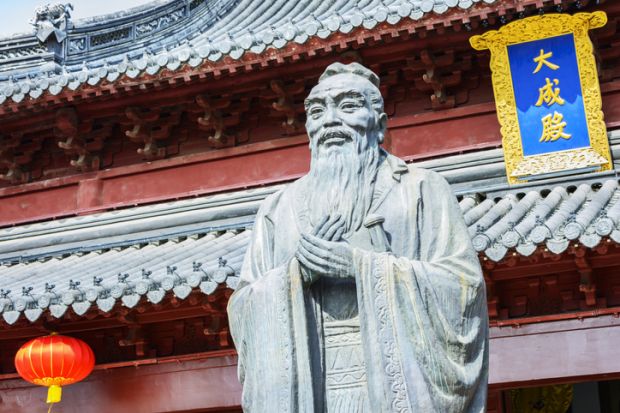

He has also been grilling universities with Confucius Institutes about their contracts with Chinese partners.

In private, some university leaders have been fiercely critical of the approach, believing that they were under pressure to end these links without transparent guidance from the OfS.

Scholarships issued by the Chinese Scholarship Council have faced increased scrutiny in recent years after reports emerged suggesting recipients must swear loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party and pledge to act in their nation’s interests.

There have also been concerns about Chinese students spying on one another when abroad, following evidence that students who speak out against the Chinese government while on British campuses may be reported to their local embassy by their peers.

New laws that came into force in 2024 strengthened duties on higher education providers to secure free speech on campuses, including protecting against foreign interference.

Guidance released by the OfS prior to the introduction of the new laws states that scholarships funded by a foreign government that are conditional on recipients accepting the basic principles of the ruling party are “very likely to undermine free speech and academic freedom”.

It adds that, if recipients are bound to accept direction from a foreign country’s government via its diplomatic staff, there is a risk that students could be directed “to suppress or monitor speech at the English provider where they hold those scholarships”.

However, the law only states that universities must take “reasonably practicable” steps to secure freedom of speech.

Smita Jamdar, partner and head of education at Shakespeare Martineau, said it is “not unusual” for scholarships to have terms attached, such as having to abide by the funder’s code of conduct and not bring them into disrepute.

Conditions of a scholarship for international study offered by the government of Dubai, for example, state that students must “represent the United Arab Emirates in an honourable manner and refrain from any act or behaviour that violates laws, ethics, or harms the country’s reputation, as well as refrain from engaging in any political activities”.

Jamdar said it was “unrealistic” for the OfS to expect institutions to only accept students who were actively choosing not to enter into scholarships that could restrict their freedom of speech. “It logically can’t work because it would be saying almost that the best way to secure their freedom of speech is not to admit them at all.”

She said it was important for institutions to make clear to all students that they must not restrict anybody else’s freedom of speech once in the UK, including “seeking to get them in trouble with third parties for how they exercise their freedom of speech on campus”.

Jamdar said she did not believe it was reasonable to expect universities to close Confucius Institutes because doing so mid-contract could have legal implications.

There are currently about 20 Confucius Institutes on university campuses in England. “It may not be easy for you immediately to introduce new requirements and new expectations but you’d be expected to try [when your contract] comes up for renewal,” she said.

However, other university leaders agreed with Ahmed that universities should be doing more to prevent foreign interference.

Anthony Finkelstein, vice-chancellor of City St George’s, University of London and former chief scientific adviser for national security to the British government, said although it is vital to continue teaching about Chinese culture in the UK, doing so “under the sponsorship of the Chinese government is highly problematic and, in my judgement, ill-advised”.

“It is increasingly clear not only does this impose both explicit and implicit restrictions on what can be done, it creates dependencies, financial and otherwise, [and] may also impose more serious restrictions, including restrictions on the academic freedom of staff.”

Research by the UK-China Transparency Group has found that the hiring process for Confucius Institutes – generally led by Chinese authorities – can be “highly discriminatory”, with Chinese staff “obliged to undermine free speech”.

Finkelstein added that he believes it is “right and proper” that the OfS looks into intervention by foreign states and feels that some universities have “turned a blind eye” to the issue.

The OfS declined to comment.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?