Major donations by Robert Smith to Morehouse College and by Michael Bloomberg to Johns Hopkins University both promised debt-free education to graduates. Across two substantially different institutions, however, both are seen as falling well short.

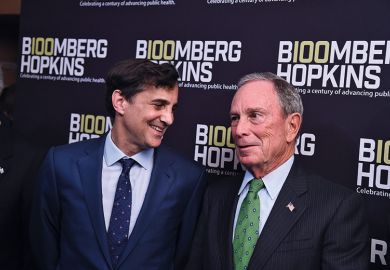

At Johns Hopkins, one of the wealthiest US universities, the $1.8 billion (£1.4 billion) donation back in November included pledges of increasing minority enrolment and helping inexperienced students navigate college, yet without details of how extensively that would happen.

At Morehouse, a historically black college, Mr Smith’s commencement surprise this month – an estimated $40 million to cover the entire student debt of the graduating class – sidestepped the fact that about half of its entering freshmen don’t last long enough to toss their mortar boards.

The cases reflect a pattern, several experts said, of US universities and their allies making impressive efforts to get more low-income students on to campuses, then lacking the resources to help guide them through to completion.

“This explains why the past decade has seen such a switch in emphasis among policymakers and intermediary organisations and foundations on college completion,” said William Casey Boland, an assistant professor of public and international affairs at City University of New York Bernard M. Baruch College.

“Despite this attention, completion rates haven’t increased by much.”

Counselling to help students with little family experience in higher education “doesn’t really exist out there – it’s the missing link”, said Anthony Carnevale, a research professor and director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

“Dollar-for-dollar,” Professor Carnevale said, “an increase in access is less effective than an increase in academic and career counselling.”

Johns Hopkins has a $4 billion endowment, and Mr Bloomberg’s additional $1.8 billion is enough to generate some $80 million in student aid annually. The university has spoken of using some of that money to boost minority enrolment and counselling of high-need students. But despite six months of promises that Johns Hopkins would clarify how much of the gift actually will be used for those purposes, it has not done so.

And, two months after accepting its latest freshman class, the university has not said whether the gift produced any significant reduction in the overwhelming majority of Johns Hopkins students coming from the nation’s wealthiest families.

As such, the gift does not currently appear especially transformative, said Robert Shireman, director of higher education policy at the Century Foundation. “There is no indication that it will change the elite college dynamics,” Mr Shireman said.

As a historically black college, Morehouse appears to do much better than most US universities in guiding students from disadvantaged backgrounds, Dr Boland said. “Extra attention to the student’s background and an embrace of their community” – common features of minority-serving institutions – are shown by research to boost completion rates, he said.

Still, Morehouse has graduation rates of about 38 per cent within four years and 56 per cent within six years. Those figures are far better than the averages for black men nationwide, but still demonstrate the challenges facing even a benevolent billionaire such as Mr Smith.

“Both the Hopkins and Morehouse gifts are generous,” said Jessica Thompson, director of policy and planning at the Institute for College Access and Success. “But both underscore the need for policy solutions at scale, not philanthropy, as the most effective and equitable way to address college costs and debt.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?