Numerous studies have shown the benefits for Western universities of recruiting international students, finding that a diverse student body exposes students to different cultures and ideas, helps them develop globally relevant skills and enriches classroom discussions.

But recent data suggest that domestic students often fail to perceive these benefits, and that, in some cases, they are decidedly lukewarm about learning alongside foreigners.

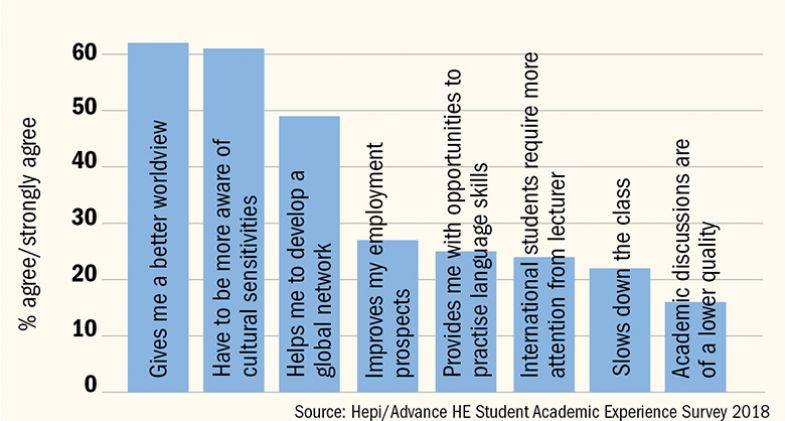

One survey of more than 12,000 UK undergraduates found that, while a majority felt that studying alongside international students gave them a “better worldview”, nearly a quarter (24 per cent) believed that overseas students “require more attention from the lecturer”.

Meanwhile, more than a fifth (22 per cent) said that international students “slow down the class” and 16 per cent said that their presence means that “academic discussions are of a lower quality”, according to the 2018 Student Academic Experience Survey, conducted by the Higher Education Policy Institute and Advance HE.

This is not the first evidence that raises uncomfortable questions about the role of international students in the classroom. An Australian study from 2012 found that adding international students to a tutorial – or domestic students from non-English-speaking backgrounds – “leads to a reduction in most students’ marks”. “The effect is strongest as felt by students from English-speaking backgrounds,” according to the paper, published in the Economics of Education Review.

How, then, can the benefits of having international students in the classroom be maximised?

Vincenzo Raimo, pro vice-chancellor (global engagement) at the University of Reading, said that the Hepi/Advance HE study should provide a “wake-up call” to universities to do more to “engage our domestic undergraduate students with the benefits of internationalisation”.

“If [domestic students are] saying that the international environments that most UK universities now have aren’t equipping them in the way that they expected universities to do, it means that we’re failing somehow,” he said.

Blessing and burden: students on overseas learners

Mr Raimo added that universities can “do more” to ensure that the curriculum and student experience is “more international”, which would lead to domestic students becoming “more open to working with” international students.

Increasing the number of domestic students who study abroad would also help them “understand better some of the challenges that international students face when they come to the UK”, he argued, and mean that they “engage more with” foreign classmates.

Colleen Ward, director of the Centre for Applied Cross-cultural Research at Victoria University of Wellington, who has conducted research on domestic New Zealand students’ attitudes towards international students, said that it is “naive to think that introducing international students into institutions of higher education is going to result in transforming their domestic peers into aware global citizens – even though there is the potential for this to occur”.

“There are many reasons that negative attitudes toward international students abound. Our research has shown, for one thing, that international students can be seen as a source of competition and threat, especially when they represent a relatively high proportion of enrolments,” she said, adding that instructors also often “lack the motivation, confidence or skills to optimise the benefits of a culturally diverse class”.

Gigi Foster, associate professor in economics at the University of New South Wales and author of the Australian study, said that there is “much more that could be done to improve the way we handle the increased diversity in Australian student populations”, citing an increased emphasis on English language competence on campus, “more organised and higher-resourced fighting against organised cheating” and greater celebrations of students’ cultural diversity as ways in which institutions could improve.

Elspeth Jones, emerita professor of the internationalisation of higher education at Leeds Beckett University, added that, at the UK “government policy level, there needs to be an awareness that constantly focusing on increasing mobility is not the sole answer to developing global perspectives”.

“Internationalisation of the curriculum at home and broader engagement with diversity is the only way to offer all students the benefits of internationalisation, rather than simply the mobile elite,” she said.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Are students fans of peers from abroad?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?