The chief science adviser to the prime minister of New Zealand has accused scientists of displaying “hubris” and “arrogance” when they comment on government policy.

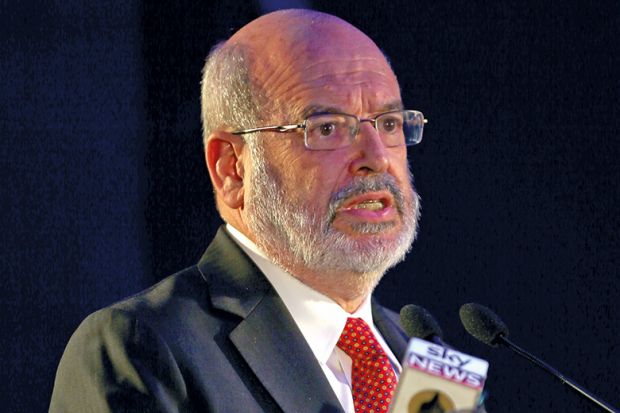

Sir Peter Gluckman, who also chairs the International Network for Science Advice to Governments, levelled a series of sharp criticisms at researchers and science organisations during an event in Brussels that debated the role of policy and evidence in a “post-fact” world.

He argued that scientists needed to appreciate that politicians made their decisions based on values as well as scientific evidence.

“Individual scientists, professional and scientific organisations too often exhibit hubris in reflecting on policy implications of science,” Sir Peter told delegates at “EU for facts: evidence for policy in a post-fact world”, held on 26 September.

“This arrogance can become the biggest enemy of science effectively engaging with policy – the policy decisions inevitably involve dimensions beyond science.”

Scientists needed to appreciate that political ideology, financial and diplomatic constraints, and “electoral contracts” also had to be taken into account by politicians, Sir Peter said. “It is important that [scientific] knowledge is provided [to policymakers] in a way that does not usurp the ability of policy process to consider these broader dimensions: otherwise trust in advice can be lost as it becomes perceived as advocacy,” he argued.

He also said that he avoided using the “somewhat arrogant” term “evidence-based policy”, preferring “evidence-informed” instead. Meanwhile, “too often academy reports are focused on academic demonstration rather than meeting policy needs or answering an unasked question”, he added.

Search our database for the latest global university jobs

Similar warnings have come from other figures in science. Last year, Jeremy Berg, the editor-in-chief of Science, said that academics have too often ventured into giving policy prescriptions rather than just explaining the evidence, for example in the area of climate change.

Although he named no names, Sir Peter also warned that “individual scientists” were now using their “scientific standing” to make claims “well beyond the evidence and their expertise”. Universities may also “over-hype” their science, he added.

In addition, the pressures of “performance measurement, bibliometrics, and the quest for societal and industrial impact” also have the potential to undermine public trust in science, he said, “due to perceived or actual conflicts of interest and the potential to affect the behaviour of individual scientists”.

At the same conference, Carlos Moedas, European commissioner for research, science and innovation, argued that to combat a “crisis of confidence” in science, there needed to be online “places of trust for scientific advice”, just as sites like Mayo Clinic or WebMD were trusted sources of medical advice.

Such sites would be “where citizens know that science is genuine. Where the process is explained. Where they can check the sources. Where they can access the data themselves,” he said.

“So I believe in the future there will be two types of internet. The one you trust and the one you don't,” he added.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?