Lauren Elkin’s memoir and cultural history Flâneuse was published in 2016, to a great deal of critical attention. Journalists and readers were fascinated by what they saw as a revisionist history of the ownership of city streets and the public phenomenon of the empowered female “street haunter” as spectator.

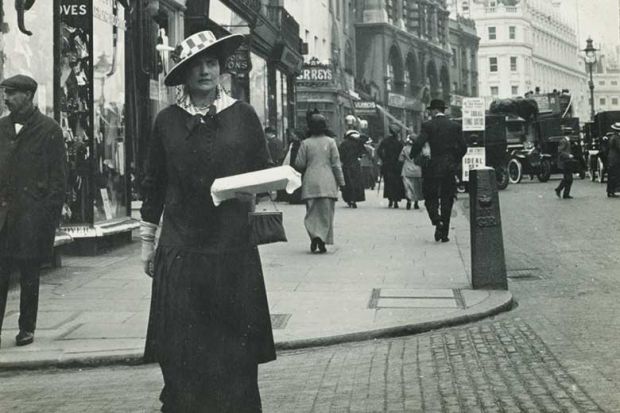

The flâneur of the popular imagination, a (crucially male) figure who walks the streets of a city, interested and observing yet ironically detached, was more compelling when reimagined as a woman. The very masculine flâneur has been a contested figure in literary criticism for a while, however. Deborah Parsons’ 2000 monograph, Streetwalking the Metropolis, positioned both flâneur and flâneuse as “ambiguously gendered” and explored at length precisely how flânerie and gender complicate each other. Elizabeth Evans’ new book begins here. She takes as her focus the middle-class woman in the city, although a footnote clarifies that middle class is a “broad” category, “encompassing both lower-middle-class service workers and their upper-middle-class employers”. She is thus able to discuss the barmaid and the shop girl alongside the New Woman typist and the leisured middle class of Virginia Woolf’s circle. Women’s flânerie is then further complicated as not merely about agency in the streets of the city, but a poor woman’s sense of her own agency as against an affluent woman’s very different attitude to both her own and the poorer woman’s agency.

In Evans’ account, the attraction of the public space and the relative safety (or constraint) of the private space are continually in play as the “new public women” of 1880 to 1940 walk the streets, observe and are observed, and struggle to perform interested detachment with and from their surroundings. This is not especially new, but where the book comes into its own is in its examination of “colonial subjects of color” as city walkers, and how a visible racial identity affects an understanding of flânerie ’s “unobserved observer” ideal.

Evans coins the phrase “reverse imperial ethnography” to describe how the writers B. M. Malabari, T. M. Mukharji, A. B. C. Merriman-Labor and Duse Mohammed Ali reveal London as “a familiar city made strange by its vision through foreign eyes”. They all present themselves as othered observers, with an eye to a white British readership, and each thus engages, implicitly and explicitly, with precisely the kind of anxiety around visibility and detachment that troubles the “new public women” of fin-de-siècle white British fiction. At the same time, these colonial writers provide an account of the women they see on the streets in terms of their own status as visible observers. Malabari, for example, reflects on the “general freedom of movement” of English women in public, and the “earnest sympathy and self-confidence” with which they will meet one’s eye. The watchers are watching the other watchers.

Everyone loves a book with maps. Evans has mapped out sites of narrative significance in Henry James’ The Princess Casamassima, Amy Levy’s The Romance of a Shop, George Gissing’s The Odd Women, H. G. Wells’ Ann Veronica and Virginia Woolf’s Night and Day. She has, wisely, not attempted a map of Dorothy Richardson’s Pilgrimage.

Rebecca Bowler is lecturer in 20th-century English literature at Keele University and the author of Literary Impressionism: Vision and Memory in Dorothy Richardson, Ford Madox Ford, H. D. and May Sinclair (2016).

Threshold Modernism: New Public Women and the Literary Spaces of Imperial London

By Elizabeth F. Evans

Cambridge University Press

280pp, £75.00

ISBN 9781108479813

Published 6 December 2018

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: On wandering and watching

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?