No one could ask for a more congenial companion than Emily Thomas on her 2,000-plus year journey through The Meaning of Travel for major Western philosophers from Plato to Simone de Beauvoir. Mainly addressing the uninitiated “common reader”, her book incorporates Thomas’ personal experiences in Alaska and the Arctic Circle into established philosophical perspectives on travel – everything from tourism to space exploration. Along the way, she contends, “Asking questions about travel, and exploring ways philosophy has changed travel, can help us think more deeply about our journeys.”

Most of her dozen or so chapters on the significance of travel can be classified under traditional philosophical categories – ethics, epistemology, theology, logic, aesthetics and so on – and include general discussion of the intellectual and emotional enrichment that travel provides. Thus, while Montaigne maintains that exposure to other societies “forces us to expand and rethink what we know”, Bertrand Russell argues that “living abroad diminishes prejudice”. Both, however, leave open the question of what, if any, practical benefits accrue from travel.

For increasing numbers of “natural philosophers” such as Francis Bacon, data collected by early 17th-century explorers helped produce insights based on direct observation – regardless of whether the collected data had immediate application. Margaret Cavendish, on the other hand, insisted that newly acquired knowledge was valuable only when it had practical consequences – when “we know how to Increase our Breed of Animals, and our Stores of Vegetables, and to find out the Minerals for our Use”. Thomas is at her best explaining these sorts of disputes among philosophers, often by positioning antagonists in direct dialogue.

She also recounts the disagreement between Immanuel Kant and Mary Wollstonecraft arising from ideas introduced by Edmund Burke’s Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful (1757). Kant argued for a gendered distinction between the “sublime” and the “beautiful”, insisting that “men should be sublime, and women should be beautiful”; whereas Wollstonecraft rejects (categorically!) any such idea that discounts women’s intellectual beauty. Burke had helped instigate the dispute by distinguishing between the “pleasurable terror” arising from the sheer magnitude of the Swiss Alps or the ocean’s depths and the quasi-erotic sensations afforded by the neck and breasts of a beautiful woman: “the smoothness; the softness; the easy and insensible swell”. (Applying Burke’s distinction, even Wyoming’s suggestively named Grand Teton Mountains would be considered more “sublime” than “beautiful”.)

As a further instance of philosophical contentiousness, Thomas examines the dispute between Ralph Waldo Emerson and his disciple, Henry David Thoreau, over the meaning and value of Nature. She reminds us that, for a student of Plato such as Emerson, “our world is merely an imperfect shadow” of another, more fundamental domain, “concealing the deeper [transcendent] reality of its creator”; whereas for Thoreau “nature is a power in itself”, attesting to the immanence of God. As throughout much of her book, she does not attempt to arbitrate among her subjects. Rather, she guides readers to where previous research has addressed the issues at hand.

The ethical implications of material objects such as maps, microscopes and telescopes also figure prominently in Thomas’ discussion of philosophers and travel. Reminding us of Brian Harley’s conclusions in his article “Deconstructing the Map” (published in 1989 and so well before the existence of Google Maps), she notes that cartographers were engaged in the “process” of guiding our perceptions, not simply representing objective reality; maps embody political and moral relativism through how they depict our three-dimensional world in two dimensions.

In her longest chapter, mainly devoted to Margaret Cavendish’s Blazing World (1666), Thomas identifies a tradition of philosophers engaging in “thought experiments” through fictional travel narratives, including Thomas More’s Utopia (1516) and Cyrano de Bergerac’s Journey to the Moon (1657). She could easily have included Gulliver’s visit to the Academy of Lagado, where crazed Projectors attempt to turn excrement back into food. Similarly, Cavendish’s tale of an abducted woman at the North Pole rescued by Bear-men includes a critique of microscopy for failing to “discover the interior motions of things” as well as for misrepresenting “exterior shapes and motions” by magnifying distortions. Yet Thomas adds that “today, we know microscopy has oodles of uses” – the understatement of all understatements.

Her chapter on the ethics of ecotourism, on the other hand, is especially timely. Referring to a problem that has become known as “the ‘paradox’ of doom tourism”, Thomas recapitulates the arguments for and against her own decision to visit ecologically at-risk places such as Denali Park before it is too late. Here again, she recounts arguments put forward by others such as Allen Carlson, whose 1979 paper “Appreciation and the Natural Environment” weighs the costs and benefits of ecotourism: further damaging the environment versus increasing awareness of the problem.

Likewise, Thomas’ chapter on travel as an activity gendered as male reminds us of the cultural bias against female travellers. This is one of the few instances where she strikes out polemically – and literally – on her own, arguing that the male gendering of travel is problematic because it discounts the experiences of significant female travellers such as Mary Kingsley (who published Travels in West Africa in 1867). It thereby discourages women from experiencing the world beyond their assigned domestic sphere – something Thomas’ own travel adventures help to combat.

On occasion, she travels somewhat beyond her own comfort zone – and not just when she plods through a waist-high snowdrift along Alaska’s Dalton Highway. Among the book’s dozen playful illustrations is one of Gulliver representing the idea that relative size is not an index to moral understanding because “small things can be just as valuable as large ones” and “the size of a thing need not affect its value”. While some male readers will undoubtedly find this reassuring, Thomas mistakenly views Swift’s Lilliputians as sympathetic miniature “thinking, feeling being[s]” rather than diminutive embodiments of the absurd pride and pettiness Swift was satirising.

Overall, however, The Meaning of Travel succeeds in offering an engaging primer on how travel has transformed both what we know and how we think. Occasionally, Thomas risks talking down to her readers, as when she recaps Genesis’ story of The Fall, belabours the distinction between gender and sex or defines aesthetics as “the study of beauty and art”. But even if undergraduates feel somewhat patronised by such statements of the obvious, her chapter on “Sex, Education, and the Grand Tour” will likely ring true to their own travel experiences in quest of sex, drugs and rock and roll.

From what Thomas calls her “vintage” preliminary travel tips – for example on how to “avoid being eaten” – to her “vintage” warnings in the epilogue not to “bore people with travel talk” when you get back, her breezy style prevents her account of travel philosophy from ever boring readers. Along the way, she forever puts to rest Morris Zapp’s assertion, in David Lodge’s 1975 novel Changing Places, that “travel narrows”. What bitter irony that this book should appear in the very year Brexit will be implemented and governments around the world imposed lockdowns on their citizens to prevent the spread of Covid-19.

Richard J. Larschan is English professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth.

The Meaning of Travel: Philosophers Abroad

By Emily Thomas

Oxford University Press, 245pp, £14.99

ISBN 9780198835400

Published 27 February 2020

The author

Emily Thomas, associate professor in philosophy at Durham University, studied for her undergraduate and master’s degrees at the University of Birmingham, where, she recalls, “the philosophy department was exceptionally friendly: it taught me how to debate critically and amicably”. From there she went on to a PhD at the University of Cambridge, which proved “wonderful in other ways”, and she “fell into history of philosophy. I was at Christ’s College, which probably helped: it has a (freezing!) outdoor pool, overlooked by statues of 17th-century philosophers Henry More and Ralph Cudworth.”

Although her previous writing has been on more specialist philosophical themes such as theories of reality, Thomas sees many links with The Meaning of Travel, which is aimed at a more general audience. For a start, she explains, “I had already worked on many of the philosophers involved: Descartes, John Locke, Margaret Cavendish. My earlier work also fed into the book in unexpected ways. For example, I’ve worked on Henry More’s theory of space, which affected mountain tourism. I’ve also worked on issues around women in philosophy, which carried over well to women in travel.”

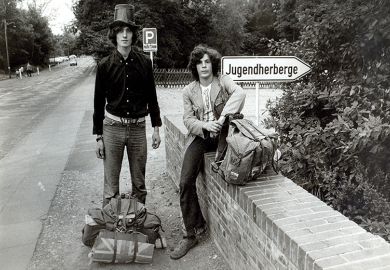

Always a keen traveller, Thomas looks back on her twenties as “a cycle of working, saving and spending all my money on travelling. I’ve spent several years backpacking by myself, through parts of the Middle East, Asia, the Americas…Travel has always been a privilege, but the current, worldwide travel restrictions are unprecedented. We are losing opportunities to see unfamiliar places. But real-world travel isn’t the only way of engaging with the unknown. We can also armchair-travel: learn about the world from the fireside, talk, read books. The world is changing swiftly right now, and I think we’ll need all the understanding and reflection we can get.”

Matthew Reisz

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: A grand tour of thinkers’ trails

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?

![Artistry Thomas and William Daniell, ‘Part of the Interior of the Elephanta [Temple]’, in Oriental Scenery (1800). Yale Center for British Art Artistry Thomas and William Daniell, ‘Part of the Interior of the Elephanta [Temple]’, in Oriental Scenery (1800). Yale Center for British Art](https://www.timeshighereducation.com/sites/default/files/styles/teaser_standard/public/p40_aquatint.jpg?itok=P2P0CZXE)