When we at the University for the Creative Arts opened the Institute for Creativity and Innovation in Xiamen, China this autumn, we weren’t expecting headlines. After all, new overseas campuses have become a familiar story as the UK’s renowned universities do everything they can to protect and enhance their income streams.

Except that, for me, such a narrow, commercial rationale entirely misses the point of what transnational education is about. Rather, it is about meaningful collaboration that benefits students in both countries, equipping them with a rich array of cultural reference points and preparing them for a career that is global in scope.

When I first came to the UK from Palestine as a fine art undergraduate, I was hungry to learn from the very best in my field while becoming more familiar with Western culture. My background was vastly different from that of my classmates, who had enjoyed a single way of learning throughout their lives and had their own set of assumptions around the very concept of fine art.

That’s why, when I talk about this, my voice isn’t coming from a place of fashionable political correctness. I have lived the life of an international student; I had to learn to embrace my own way of seeing the world. That’s why I’m so passionate about helping others come to the same understanding. And while the international collaborations we are forging at the University for the Creative Arts naturally focus on creativity, the principles underlying our approach remain true whatever the subject matter.

When we first joined forces with Xiamen University, we had a series of honest conversations about the needs of Chinese learners. Our job is to prepare students to become future leaders in the creative industries, but we know we won’t get there by simply exporting the same curriculum we deliver at our campuses in Surrey and Kent. It is essential to co-create a curriculum that’s grounded in the cultural references our Chinese students are familiar with.

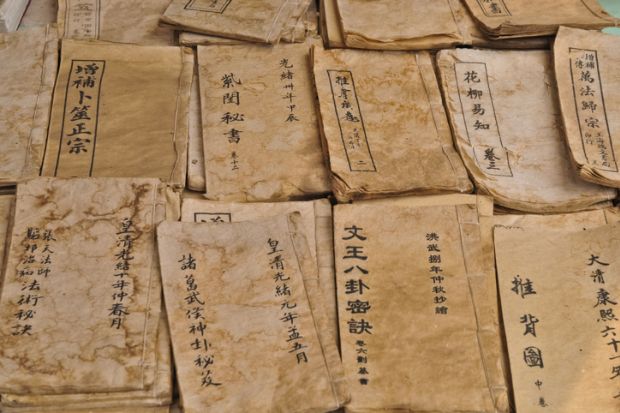

Our Chinese students have grown up watching different films from our UK students, and walking through towns with markedly different architectural styles. The beginnings of their artistic development may have started with calligraphy or scroll paintings. Not to recognise these things would smack of arrogance.

We’re also mindful that the Chinese education system deploys very different teaching and learning methods, so we’ve carefully considered how we transition our Chinese students away from the linear ways of learning that they’ve been used to, to equip them with a broader perspective. How we teach can be just as important as the curriculum itself, and universities need to recognise the different cultures and traditions of learning that will have shaped a person’s approach to education.

UCA’s approach to this has been to offer personalised learning experiences that empower students to develop their own creative vision. When our first cohort of Chinese students graduates, they’ll have the same ability to innovate, problem-solve and apply their creativity as their UK counterparts.

This kind of collaboration also offers a range of benefits for UK students, many of whom benefit greatly from having the opportunity to study aboard for a term as they consider their subject of choice in a global context. Indeed, the creative industries are increasingly international in scope, and very few fields operate without considering the needs of global consumers. Our future fashion graduates may well debut their catwalk collections in Tokyo, and our graphic designers may find lucrative work designing eye-catching packaging for Chinese products.

Throughout history, universities have continually evolved their courses to factor in technological advances and the ceaseless evolution taking place in industry and business. Global partnerships are the latest iteration of this – universities must bring together students, researchers and educators from different continents to remain relevant and reflect modern society.

In my case, after completing my BA in the UK, I stayed on, studying for an MA and a PhD. Throughout that period, and throughout the academic career that followed, I have continued to practise as a fine artist.

Today, those who follow my work are just as likely to be Chinese as they are to be British or Palestinian. China has, in recent years, established itself as an important stop on the exhibition circuit for artists working in all mediums. I was recently involved in a show at Beijing’s Today Art Museum that saw about 60 international artists showcasing bold work that explored notions of identity and conflict.

The truth is that you simply cannot make it as a professional, creative or otherwise, if you refuse to engage with other cultures, or if you are blind to opportunities that exist outside your own country. That’s why higher education institutions must reject Western-centric notions of education.

Instead of colonising the overseas curriculum, we need to be asking: “How can we learn from one another?”

Bashir Makhoul is vice-chancellor and president of the University for the Creative Arts.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?