A few weeks ago, we were in Indonesia to work with a group of about 20 university rectors. The event was opened by the secretary general of the national Ministry of Higher Education, Research and Science.

The purpose of the meeting was to explore the possibility of these rectors forming a community of practice where they could work with one another to address pressing common challenges. These rectors were, in the words of one participant, “not [from] the top universities”. They were leading the kinds of institutions that are the bread and butter of many public systems serving the majority of the post-secondary needs of the nation.

During one of the introductory sessions, the rectors described their institutions – their particular strengths and qualities. One noted that behind the university was forest and in front the sea, which made forestry, ecology and marine sciences sensible emphases. Another described his institution’s location on a borderland between his country and another, and that the ongoing collaboration and tensions of serving border communities had formed a defining identity for the institution. This informed its academic programmes, and situated the institution as expert in these matters, such that the government sought advice from its experts when dealing with border issues.

One by one, each rector situated his or her institution in its unique context and described how that informed its mission and identity. Their ready ability to articulate the unique value proposition of each institution was remarkable.

We have spent time on many campuses in the US and in other countries, and in many cases the defining feature is expressed solely in terms of the compass. “South Eastern [Insert the name of a state or province here] University”. The marketing proposition to prospective students is that this is a good institution near you.

But despite these attempts to be distinctive, there is a marked tendency for many of these colleges to act as if they were the most prestigious institutions in their neighbourhood, even though they lack the resources to fulfil that aspiration. They have tried to be excellent in many academic areas and to meet the needs of all groups and enterprises in the region. In reality, few public universities have the resources to compete on that level, so the outcome has been a blurry, amorphous mission that cannot be fulfilled.

They have consciously or unwittingly overlooked the great potential power that can be unleashed by an unswerving commitment to place.

One particularly fine example is Portland State University. In the 1990s, PSU was an under-resourced institution struggling within a state system dominated by the University of Oregon and Oregon State University. There was a lack of clear identity and mission within PSU and a prevailing sense that it was a “lesser than” institution.

Then a new president, Judith Ramaley, arrived and led a series of conversations about what unique role PSU might play. What slowly emerged was a consensus around the radical idea of being an institution in, of and for Portland, Oregon.

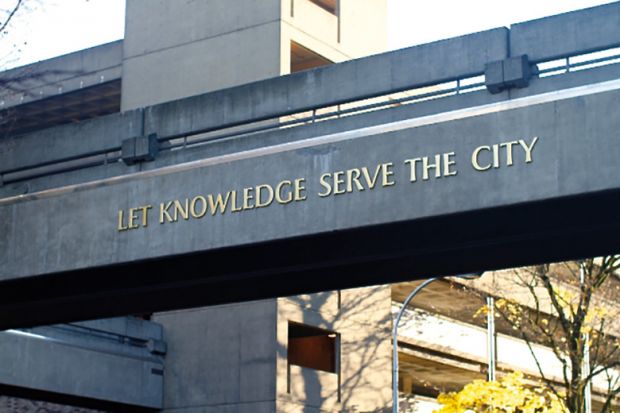

“Let knowledge serve the city” became the institution’s new motto (and it is still emblazoned on a prominent bridge on campus). That commitment led to a shifting of practices – faculty hiring and faculty rewards were aligned to this new purpose. Institutional resources were provided to academic departments that engaged in substantive curricular reform around the ideal. Courses that enabled students to work in partnership with community groups on pressing real-world problems (“service learning”) exploded. And the state legislature took notice and allocated new resources to the institution.

As the university evolved, its faculty, staff, administrators and students began to take pride in their university’s unique mission and role. In the next decade, PSU would go from being ranked among fourth-tier regional institutions to a second-tier national research university. It also became first choice for many students inspired by the commitment to community engagement and a focus on relevant, pressing real-world issues.

The benefits of having a clear mission are well known. It helps an institution to decide how to allocate resources, where to place its bets. It defines and celebrates distinctiveness and helps to answer the question “with all the choices students have, why should they come to us?”

One of the Indonesian rectors, in describing his institution’s mission, explained that many students who once would have opted for a university in distant Jakarta now choose to come to his because they could see its relevance to their community and to a career in the province. Having a clear mission also gives people who work in an institution a sense of meaning about their work; it enables them to see how they are contributing to some larger purpose.

Creating a clear mission means being open to the influence of a larger academic community and the surrounding populace. It means drawing in people across campus and empowering them to make the ideal their own. It means directing resources to efforts that build strengths and being willing to bear the political pressure of short-changing other areas.

A mission, particularly one committed to place, requires constant tending. Neighbourhoods and economies change just as much as faculty change. This means the mission needs to adapt and evolve as externalities change, and at times the institution’s mission will lead and guide change in the communities served. And there will be instances where the mission will cause an institution to resist change to protect and serve an essential underlying community value.

No one would claim that leading change at a university is easy. But without having a clear direction, without having a means of deciding where to focus attention and resources, without clarity of purpose, it’s impossible.

Matthew Hartley is executive director, and Alan Ruby is a senior fellow, both at the Alliance for Higher Education and Democracy in the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education.

Write for our blog platform

If you are interested in blogging for us, please email chris.parr@tesglobal.com

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Power of place can make your university uniquely strong

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?