It’s mid-January and university entrance offers have begun to arrive thick and fast in the inboxes of this year’s crop of sixth-formers.

A significant proportion – now one in six, according to the latest Ucas End of Cycle Report – will receive at least one unconditional offer from the institutions they hope to attend.

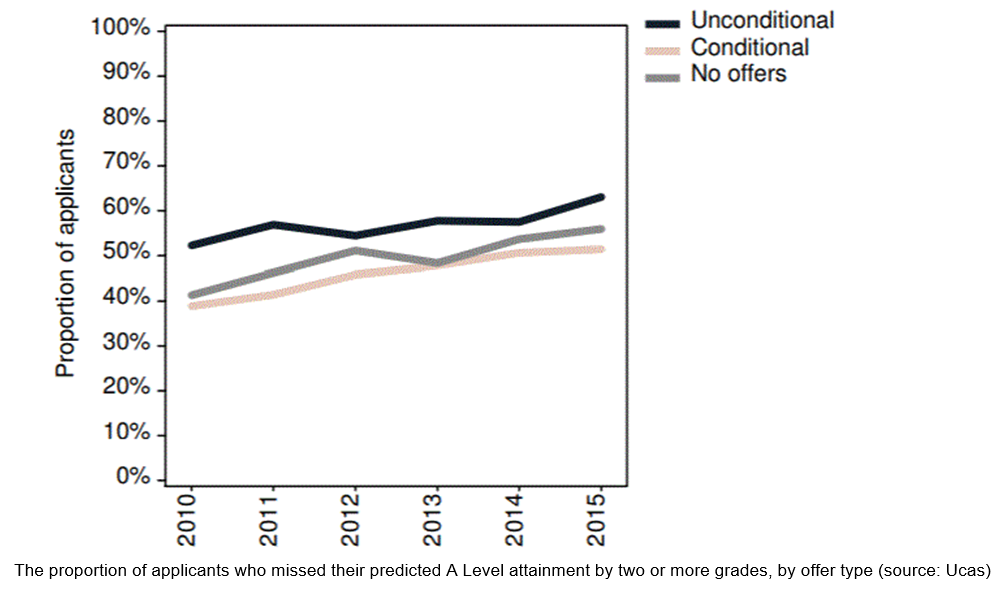

The recent dramatic growth in the issuance of such offers, which guarantee applicants a place at university irrespective of the A-level grades they go on to achieve, has heightened concerns among teachers and academics about their demotivating effect. In the face of apparently incontrovertible evidence from Ucas that they lead to underperformance (see graph below), their use has continued to expand unchecked.

Since 2013, the number of unconditional offers made each year has risen 17-fold, from 3,000 to 51,600. Over the same period, the number of institutions issuing a substantial quantity (more than 100) has increased from four to 66.

Clare Marchant, chief executive of Ucas, has said: “We need to make sure that we don’t adversely affect 17- and 18-year-old attainment by using a method like this.” Her own organisation, however, already appears to have demonstrated convincingly that unconditional offers do damage attainment.

Other worries expressed relate to the perception of unfairness among school pupils receiving very differing offers for similar courses – some extremely demanding, others not at all – and the loss of a sense of a shared enterprise in the classroom; the distortion of teachers being impelled towards inflating the predicted grades of their charges lest the latter lose out in the competition for unconditional awards; the burden of confusion and pressure placed on pupils from having to choose between very contrasting offers; and the future impact on candidates’ job prospects from underachievement in the critical exam that is used by many employers to perform an initial sift of applicants.

Since the publication of Ucas’ December report, there has been an outcry in the press over what is perceived to have been a downward spiral in admissions standards. It has been claimed that the rise in unconditional offer-making has been driven by commercial rather than educational objectives, as universities have competed fiercely for candidates in a new environment of fee-paying and uncapped recruitment.

It is true to say that the expansion has been centred on the mid- and, more latterly, lower-tariff institutions, where such offers are arguably least appropriate, with the Russell Group institutions not participating (with the exception of the University of Birmingham, the University of Nottingham and Queen Mary University of London). It is also the case that the group most likely to receive an unconditional offer has fallen over time from those predicted AAA in 2015 to those predicted BBB in 2017.

With the new year, however, a counterargument to this line of criticism has emerged. Bernard Trafford, former headmaster and chair of the Headmasters’ & Headmistresses’ Conference, has urged the making of more unconditional offers, not fewer, on the seemingly plausible grounds that two E offers from Oxbridge have in the past given young people from disadvantaged backgrounds “the break they need” and “taken the pressure off”.

He cited the case of his former pupil, the Times journalist and novelist Sathnam Sanghera, as providing a prime example of someone who had benefited from such an offer. And Sanghera himself had, coincidentally, just written a powerful short piece in his own column to the same effect.

The logic has an alluring appeal, creating the impression of a balanced debate – and, in so doing, threatening to halt the momentum towards change and a reversing of the tide that had been building. It is, however, a red herring that should be ignored. For today, we have a more powerful and precise instrument at our disposal than the blunt unconditional offer: the contextual offer.

This is a preferential offer, made for the purpose of assisting social mobility, that is lower than the standard entrance offer. Such offers have the significant advantage over unconditional offers that they maintain the incentive to work, vital in ensuring good academic results and later employment prospects. It was not always the case that pupils with two E offers exhibited strong A-level performance; and, indeed, this was part of the reason that Oxford and Cambridge eventually abolished them.

Contextual offers are at the present time widely conflated with unconditional offers. However, they are distinct concepts. Ucas policy makes clear the difference:

“As part of their contextualised admissions policy, universities and colleges may make contextual (lower) offers to flagged students. These are not connected to, and should not be confused with, unconditional offers, where an applicant’s results will not affect their acceptance. The applicant will still be expected to meet the conditions of their contextual offer.”

Universities should collectively agree to abandon the practice of making unconditional offers, which are plainly damaging to A-level performance and indiscriminate in application, in favour of much greater use of contextual offers, which can be more precisely targeted at social disadvantage. Now that the use of unconditional offers has become so widespread, there seems little potential negative impact on relative institutional competitiveness from making the change. Presently, the potential reputational damage to the entire sector from continuing along the same path appears much more significant.

The goal of reform would be a higher education system that identifies the undergraduate cohort with the highest potential and then gives every applicant a challenging but realistic grade offer hurdle to work towards. In this way, our young people would be prepared well for life, both at university and beyond.

John Law is a teacher at Mander Portman Woodward, an independent fifth- and sixth-form college in Central London.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?