With the election of Joe Biden, many are hopeful that we can move past an era of post-truth politics. The signs look positive; the veteran senator campaigned explicitly on a return to evidence-based policymaking, in contrast to the stance of populist politicians of recent times who have dismissed expertise on everything from the size of presidential inauguration crowds to the severity of the Covid-19 pandemic.

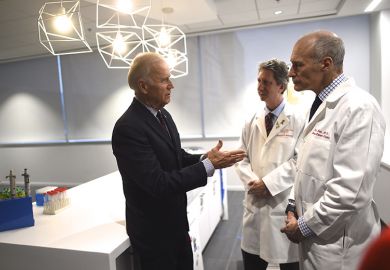

Might Biden’s inauguration represent an opportunity to go further and bring scientists and scholars into significant roles within government? After all, the president-elect is married to a college professor and has spent time as an honorary professor in the Ivy League since the Obama administration ended.

But a quick perusal of his cabinet selections reveals that his senior team includes very few professional researchers. Janet Yellen is an economist who has spent her career moving back and forth between elite universities and the Federal Reserve; aside from Yellen, the nominee for secretary of the treasury, no other nominees to Biden’s cabinet have a PhD. Miguel Cardona, Biden’s pick for education secretary, is a doctor of education and former adjunct professor at the University of Connecticut, but the overwhelming majority of his future cabinet colleagues are from a legal background.

So why do so few academics end up in politics and government? Part of the reason is structural barriers, such as lack of experience or deep ties to political parties. However, a more significant reason is the fundamental disjuncture between the kind of knowledge generated by academics and that deployed by politicians.

As the sociologist Max Weber said in his famous vocation lectures 100 years ago, the two professions require different skills, motivations and ethics. Put simply, because academics are concerned with uncovering and communicating the truth, their natural inclination when entering politics is to assume that all they must do is share their truth with the public and the world will be a better place. Weber warns us that this approach is folly. Of course, some academics have made the crossover, but the fundamental tension between science and politics observed by Weber remains, particularly given the “truth decay” seen recently in public life.

This is attested to by our analysis of memoirs of prominent academics in the social sciences who have tried their hand at politics full-time: Fire and Ashes (2013) by the one-time Canadian prime ministerial candidate Michael Ignatieff, an esteemed politics professor and public intellectual and now rector of the Central European University; Politics in a Time of Crisis (2015) by Pablo Iglesias, political science academic and charismatic leader of leftist Spanish party Podemos; A Fighting Chance (2014) by Elizabeth Warren, the Harvard law professor turned senator; and Adults in the Room (2017) by Yanis Varoufakis, the economics professor who was briefly Greece’s minister of finance in 2015.

It would be churlish to write off the political achievements of these individuals, yet none have been runaway successes in terms of achieving their desired goals.

Ignatieff’s political career flopped completely. Warren has been a popular senator in Massachusetts but her national campaigns – both for the Democratic presidential nomination and for her progressive agenda – have struggled for traction. In Spain, Podemos’ initial gains have been overshadowed by internal party controversy, while Varoufakis’ dogmatism that made him such an asset to the Syriza party became an obstacle to Greece’s required bailout from the European Union.

Each of these memoirs resonates with Weber’s insights that the truths uncovered via painstaking scholarship do not translate easily into the realm of politics and policy. But they also speak to a bigger obstacle in making the transition to politics; staying quiet or non-committal in certain situations, a political necessity at times, does not come easily to many academics.

As the former Harvard president Larry Summers, the ultimate academic-turned-political insider given his time in the Clinton and Obama administrations, put it to Varoufakis, according to the Greek economist’s memoir, academics “have a choice”. (Notably, Warren’s memoir, too, recalls the same conversation from her own separate encounter.)

“I could be an insider or I could be an outsider,” recounted Varoufakis of the meeting. “Outsiders can say whatever they want. But people on the inside don’t listen to them. Insiders, however, get lots of access and a chance to push their ideas. People – powerful people – listen to what they have to say.”

Summers’ most unbreakable rule for insiders – “don’t criticise other insiders” – is probably why we will not see scientists and academics, however talented, make the switch to politics. They may hold a little more influence in Biden’s administration, but it seems the journey from outspoken academic to trusted insider is too difficult for most scholars.

John Boswell is associate professor in politics, Jack Corbett is professor of politics and Jonathan Havercroft is associate professor in international political theory at the University of Southampton.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?