View the full list of the best universities in Europe 2017

With Brexit dominating much of the European political debate in the past year, an obvious question that arises when looking at Times Higher Education’s latest regional ranking is whether UK universities will continue to dominate in the years ahead in the way they currently do.

With the UK having more than a quarter of the universities in the top 200, and also having 15 more than its nearest national rival, Germany, it is hard to see its dominance wavering any time soon.

However, delving more deeply into the rankings data underlying this performance reveals that the UK actually trails other European countries on key measures of research success, which could make its position vulnerable.

Other key players with multiple universities in the top 100 of the Europe ranking tend to do better on important metrics such as citation impact (which makes up 30 per cent of a university’s final score in the World University Rankings). Add income from research and industry into this mix and the pattern becomes even clearer: for countries looking to build thriving research ecosystems, the UK is not necessarily the example to follow.

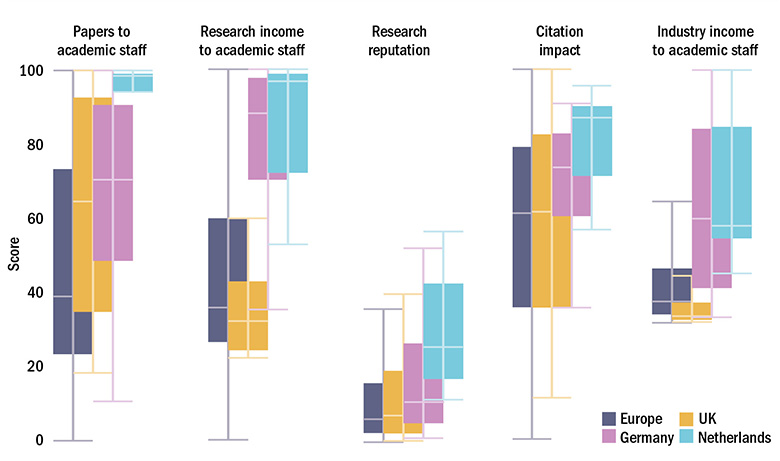

Figure 1 below shows the distribution of all universities in THE’s world rankings according to their scores in five key metrics related to research performance.

Figure 1: Selected countries v European average on key measures of research strength

The boxes and “whiskers” show where the bulk of the universities in each country sit in terms of scores on each measure (compared with the distribution of all Europe’s ranked universities).

What stands out is the exceptional performance of the Netherlands’ 13 main research-intensive universiteiten – every single one of which makes the top 100 of the Europe ranking. On research reputation, citation impact and research productivity (papers to academic staff), the Netherlands has a clear advantage over the European pack compared with Germany and the UK, which are more in line with the continent as a whole. Meanwhile for income measures – both research and industry – the Netherlands and Germany alike display major strengths over the UK.

Of course, it could be argued that the Netherlands has simply successfully concentrated all its research success and resources in a small number of top-class institutions, while countries such as the UK and Germany spread this over a larger number of universities. But are there still approaches to higher education in the Netherlands that make it essential that other countries learn from its success?

Karl Dittrich, president of the Association of Universities in the Netherlands (VSNU), highlights a strong awareness among the country’s institutions of their “public function”, which “has allowed them to view each other not primarily as competitors, but as partners”.

“Researchers actively seek out the connection with their Dutch peers,” he says, referring to initiatives such as the Dutch National Research Agenda, a set of national priorities that helps to ensure that higher education institutions and other organisations – including industry – “work towards more cooperation within the broader knowledge chain”.

It is not just the cooperative research culture that lies behind the Netherlands’ success. Dittrich and others draw attention to its quality system, too, which in terms of research is in the hands of universities through what is known as the “standard evaluation protocol”. This governs how assessments of research at Dutch universities and other institutes – which take place every six years – should operate.

Dittrich says that the quality system is one of the “important elements” of the country’s success. “Universities are in charge of the standard evaluation protocol themselves, and they re-evaluate every so often whether this protocol measures quality as best as can be,” he adds.

And although the Netherlands is successful in term of research productivity, Dittrich particularly notes that the protocol no longer considers this as an indicator for research quality. At the same time, he highlights how “societal relevance” has gained in importance within the protocol.

This point is echoed by Anka Mulder, vice-president for education and operations at the Delft University of Technology, who says that academic quality “encompasses a much broader set of criteria” than metrics such as research productivity, reputation and income.

Ensuring that universities work for students also plays a role in the country’s research success, she explains. “The contents of the study programmes, the quality of the student experience, the opinions of independent review panels and accreditation organisations and the employability of our students are all indicators of academic quality,” she says. “I believe that the strength of the Dutch university system is partly based on taking into account all these quality measures while developing the system.”

However, she also draws attention to another vital ingredient: autonomy. “It is important to note that the Dutch universities are relatively autonomous, which makes it possible to take the right decisions,” Mulder says.

Although the importance of university autonomy in shaping research success is very difficult to quantify, it has been consistently pinpointed by academics as a factor. An influential paper by a group of eminent economists in 2009 – “The Governance and Performance of Research Universities: Evidence from Europe and the U. S.” – found a positive correlation between institutions’ research performance and autonomy.

Benedetto Lepori, a professor at the University of Lugano (Università della Svizzera italiana) who specialises in research into higher education systems, is involved in exploring which factors influence European and US universities’ research performance. He says that autonomy certainly is important, but even more vital to a country’s success is healthy funding and concentrating investment in the best institutions.

“Universities can become excellent if they receive enough resources; this is usually the combined effect of a high level of resourcing in general and some extent of concentration, but level of resources is the strongest factor – the correlation between public investment in research and development and output is very high,” he says.

“Autonomy comes additionally as an enabler: well-endowed universities need autonomy in order to make strategic choices and, particularly, to hire good research staff on the academic market.”

Thomas Estermann, director for governance, funding and public policy development at the European University Association, and co-author of its latest assessment of university autonomy in Europe, says that a “high degree” of staffing autonomy in countries such as the Netherlands and the UK is “an important factor” in their success.

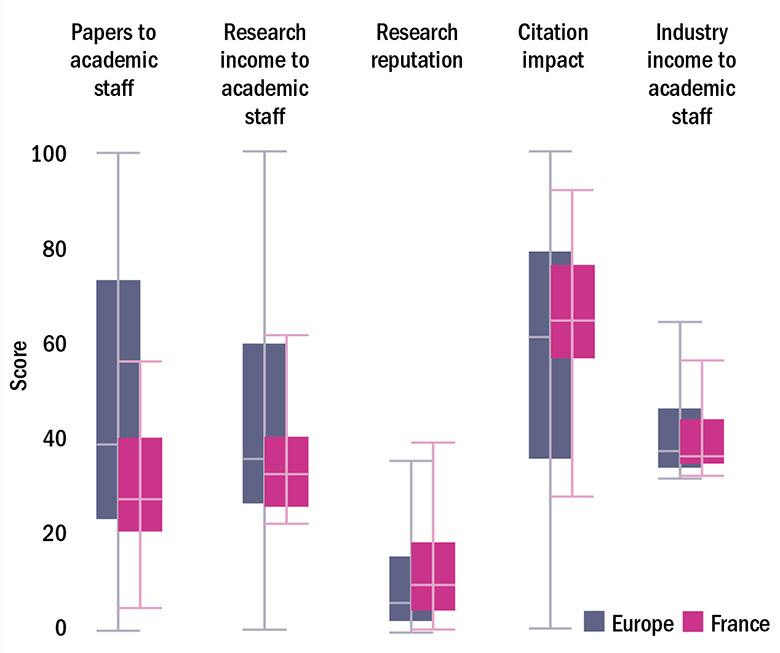

As for the alternative, central regulation of staffing in countries with a history of employing academics as civil servants, it is often suggested that this can be a brake on progress. This could explain why there is a noticeable difference when comparing the research-related rankings metrics for Europe with France, for example (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2: France v European average on research strength

Estermann says that France also has a very unusual “dual” system split between grandes écoles and universities, while Lepori points out that historically the country’s research took place in state institutes.

There have been numerous attempts to simplify the French system and make it more competitive, not least with the recent creation of “umbrella” institutions such as Paris Sciences et Lettres – PSL Research University Paris. But Estermann says that it could be decades before changes of this nature and scope make an impact.

“When you look at it comparatively, [France has] a high degree of regulation in all the measures of autonomy – which is certainly something that would need to be addressed – but those changes take a very long time.”

He refers to another case – Austria – where moves several years ago to free up staffing regulations are still filtering through; 30 per cent of university staff remain civil servants despite the reforms.

“France is a very good example of how it is very challenging to move such a large system and make reforms,” he adds.

The methods employed might not always be effective, either. For instance, Jacques Biot, president of one of France’s most successful universities, École Polytechnique, is a critic of the mergers approach to improving his country’s relative performance in research.

“Politicians have the feeling that mergers will solve the issue of French higher education, and they create even larger universities that are still not selective and not very much related to industry. We feel that this is not necessarily the right way to do things,” he says.

“We focus on being more like small-size international universities of technology.”

But what of the picture across the rest of Europe, how much is the degree of regulation, autonomy and – most importantly – funding affecting performance?

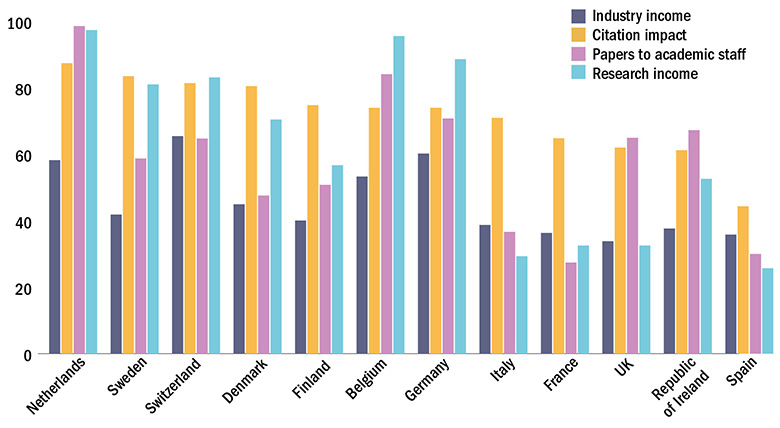

Figure 3 below shows the spread of rankings scores in key research-related metrics for every European country that has at least five universities in the top 200 of the Europe ranking. Each country’s score is the median score among all its universities in THE’s World University Rankings.

Figure 3: Median scores on key research measures for countries with at least five universities in top 200

As well as the Netherlands and Germany, Belgium, Switzerland and Scandinavian countries tend to perform well.

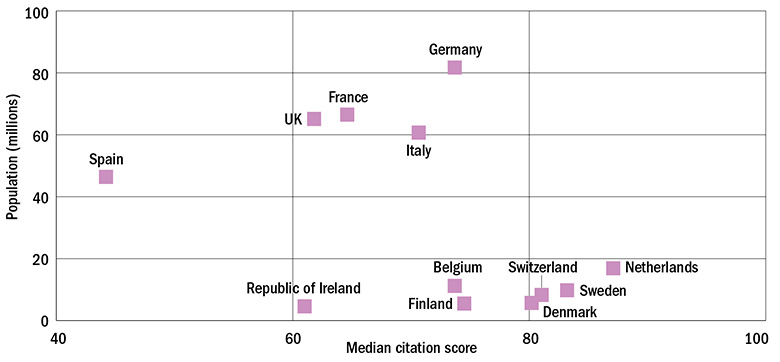

Some even more intriguing insights can be gained by looking at performance in a metric such as citation impact and seeing how this correlates with population (see Figure 4 below).

As well as the smaller research powerhouses already mentioned, the Republic of Ireland is in many respects a standout performer: despite its very small population, its median score is very close to that of much larger countries such as the UK and France.

In this, Ireland is a prime example of what a long-term focus on funding in a research system can do, a point emphasised by Jane Ohlmeyer, chair of the Irish Research Council and Erasmus Smith’s professor of modern history at Trinity College Dublin.

“I think what you are seeing here is the result of the investment that Ireland made in basic frontier research and [the system] structure in the 1990s,” she says. “If you are investing in early career researchers, postgraduates and postdocs, it takes time for that to work through.”

She adds that the latest European Commission Innovation Scoreboard ranks Ireland top in Europe for innovation outputs and on economic impact, and in the top four for human capital.

Figure 4: How does citation impact correlate with population size?

However, Ohlmeyer sounds a major note of caution over funding in light of the fall in public investment in the country since the banking crisis: the same scorecard shows that in terms of financial support, Ireland has had the third-worst relative decline of any EU country in the past eight years.

This is now beginning to be addressed, she says, and she is confident that the introduction of schemes such as Ireland’s Laureate programme (which is making grants worth hundreds of thousands of euros available to researchers working in Irish universities) will boost basic research in the country again.

The recent downturn in research funding in Ireland also shows the importance to European universities of the EU’s own funding programmes: Ohlmeyer pinpoints Horizon 2020 as having been vital when national funding was scarce. One downside of Brexit for Ireland, she adds, could be losing the UK’s influence in terms of ensuring that EU research funding continues to be dished out based on quality and excellence.

However, she also explains that the most successful nations are those that couple European funding with strong national investment.

“You cannot rely just on European funding; you have to have national funding to pump-prime the national research ecosystem to make it competitive,” she says, citing the “visionary” approach in the Netherlands as a perfect example of that.

Interestingly, though, even in the Netherlands, which more than anywhere else has reaped the rewards of a strategic and long-term approach to higher education funding and policy, there are fears that turning off the investment tap could damage the country’s standing.

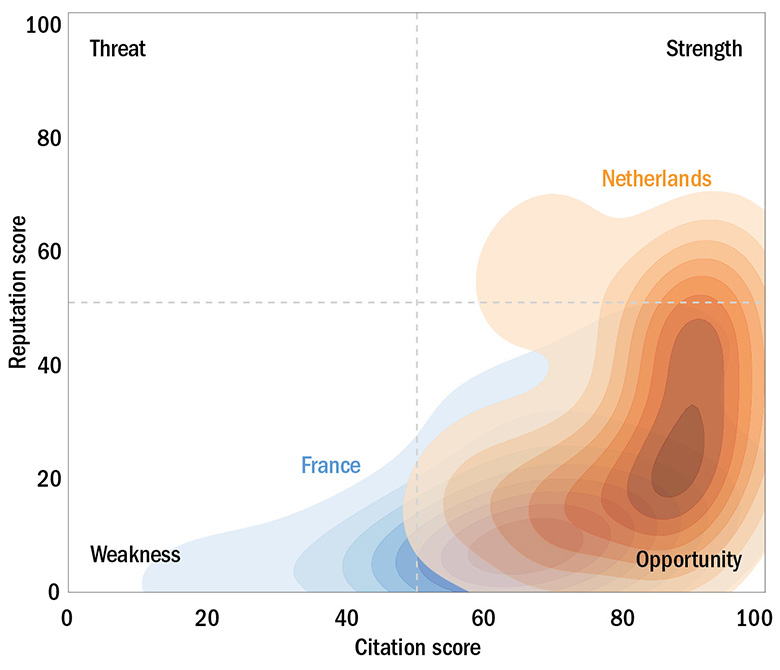

Figure 5 (below) shows how the Netherlands’ success in research – as measured by citation impact – has started to feed through to its reputation, while France lags behind on both. The graphic shows the density of each country’s ranked universities according to their scores on each measure.

Figure 5: France and the Netherlands

Dittrich warns that this hard-won reputation could be at risk because both the Dutch government and industry are now failing “to live up to the norms” for research spending that have been agreed in the past. “At the same time, we see a strong increase in R&D funding in other countries,” he adds.

“There seems to be a general – and rather misleading – belief that our current level of spending on R&D is quite sufficient because the Netherlands still does well in international rankings and such. But as we have been pointing out over the past few years – our current successes were made possible only by the investments of the past.

“The Netherlands fares well because of its knowledge economy. If we ignore the importance of continued spending on [investigative] research, we are likely to lose this strength, which we treasure so much.”

Access the latest list of the top universities in Europe

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Unseen powers

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?