Browse the full results of the World University Rankings 2025

Govindan Rangarajan took over as director of the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), India’s highest-ranked university, at the height of the coronavirus pandemic in July 2020. Taking the helm as India’s second wave became the worst Covid-19 surge in the world shaped his priorities from the start.

Rangarajan’s most pressing task has been to establish a postgraduate medical school at IISc, which so far during its 115-year history has focused on science and engineering. The university is also building a hospital to “enable our students to go back and forth between science, engineering and medicine, all on the same campus”.

In India, he explains, almost all medical institutions are stand-alone, rather than linked to universities. This is a problem because it prevents doctors from doing cutting-edge and interdisciplinary research.

“They cannot take the support of allied disciplines, and they are overrun with patient care,” he says.

“The idea of starting this postgraduate medical school was to foster clinical research and basic research in the healthcare area. Our main goal is to come up with affordable healthcare solutions, because we feel that it’s important for India and all other developing countries.”

This, too, was a lesson learned in the pandemic: “During Covid, we saw that many of the solutions were so expensive, and very few in India could even afford them.”

The medical school and hospital will provide students with qualifications that are new to India, such as an MD in radiology or a PhD in AI and healthcare. “We believe that we will be able to train a unique set of physician scientists, who will be able to take advances in science [and] engineering and implement them in clinical practice.”

The hospital will open next year, but one of the main challenges has been fundraising. While India’s corporate social responsibility law, which mandates that all profit-making companies give 2 per cent of the net profits to socially relevant causes, is an incentive for donors, giving to science is not the norm. “So we had to do a lot of convincing,” Rangarajan says.

The university managed to raise the equivalent of $60 million (£47 million) from two families, the largest gift given to any academic institution in the country, says Rangarajan, who has been leading the fundraising efforts. Compared with countries such as the US – where he studied for his MSc and PhD and worked for several years – university fundraising offices in India are not as well established. “We have set up a development office. But since, in India, people are not used to it, it’s better that the person at the top talks to them initially, so the credibility is there,” he explains.

Before Rangarajan took the top job, he led the interdisciplinary division at IISc, where he oversaw the establishment of several multidisciplinary centres and new PhD programmes. This continues to be a major focus, and the university is “trying out various strategies” to encourage interdisciplinary research. But one obstacle is the Indian funding system. Compared with the US and the UK, there is less of an incentive for academics to apply for large funding grants, which are often the drivers of big interdisciplinary research. “It has to come purely out of academic interest, which in one way is good, because no other factors come into the picture. But still it’s hard [to encourage interdisciplinary research].”

Indian universities face many challenges and have been slower than their Chinese counterparts to rise up the global rankings. The country’s National Education Policy, introduced in 2020, gave a comprehensive plan with promises to reform the entire system by 2030.

Rangarajan says the goals are “laudable” but “to actually make a difference on the ground is going to take some time”. As India’s economy improves, so will higher education, he believes.

Unlike in many countries, the number of young people in India is growing. “It is a headache for universities. We have limited capacity and so many very good students wanting to get in,” Rangarajan says. Universities also need good faculty members to teach them. “But in a way, they’re good challenges to have because we have a large pool of students who are really interested in coming into education,” he admits.

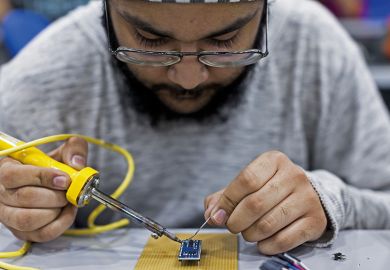

A trickier challenge is unemployment. While this is not a worry for India’s top universities, it is a problem at institutions “where the training is not up to the mark”, says Rangarajan. IISc is helping in that regard with training courses to upskill professionals in several areas, including the semiconductor industry, where there is “heavy demand”.

As Indian higher education has struggled to improve over the years, many of its brightest minds have been tempted overseas. But, according to Rangarajan, an increasing number are now returning.

“They get more international exposure and they come back, which is good for us,” he says. “And as the quality of Indian universities continues to improve, I’m sure we’ll be able to absorb more and more of these people in India.”

rosa.ellis@timeshighereducation.com

This is part of our “Talking leadership” series with the people running the world’s top universities about how they solve common strategic issues and implement change. Follow the series here.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?