“The best interview is an unethical one.”

This was not an opinion that I expected to hear from a panel discussing the ethics of interview-based research in sociology. The panel was organised as part of a recent conference held in St Petersburg, celebrating the 25th anniversary of the St Petersburg Association of Sociologists. There was, of course, no unanimity behind this view, but the all-Russian panellists largely endorsed the view that ethics committees obstruct rather than assist in the research process.

Such an attitude is particularly puzzling because – as the panellists admitted – no ethics committee has been created in Russian social sciences so far. It is not that Russian scholars are oblivious to the numerous ethical challenges associated with fieldwork. It is rather that the idea of a committee is immediately read as an attempt at an unnecessary bureaucratisation of ethical decisions that are best left to the discretion of an individual researcher.

The discussion made two things clear. One is that Russian sociologists’ distaste for ethics committees is linked to the socio-political context of Russian academia, where scholars’ negative experience of bureaucracy breeds protest against any form of institutionalisation and regulation. The other is that this scepticism is strongly reinforced by the English-language literature on ethics committees.

We might well ask why the latter is so negative. The answer is that, whether we acknowledge it or not, a good academic article is, as a rule, deemed to be a critical one. We tend to withhold from discussing processes or institutions that work well. This is understandable, for progress is largely based on the improvement of past practices. As a result, what does not work receives special attention. The drawback is that readers may not derive a full, accurate picture of the state of current practice.

As for over-bureaucratisation, this is currently the main worry of Russia-based scholars. It manifests itself in a number of ways and affects both individual scholars and institutions. One of the more recent victims was the conference’s host, the European University at St Petersburg. This is an internationally renowned research and teaching institution but it nonetheless lost its licence to conduct educational activities in 2016 because it failed to meet some bizarre bureaucratic requirements, such as failing to display anti-alcohol messages.

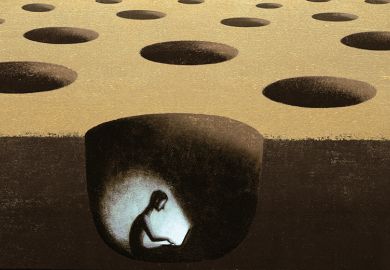

The university’s rector speaks of a “monstrous bureaucratisation”, whereby the controlling bodies display more interest in ill-advised procedures than in the actual quality of academic research and teaching. As one of the university’s professors, Ivan Kurilla, puts it: “the logic of bureaucratisation is linked to the Ministry of Education’s…total distrust of professors and students”. What has become increasingly obvious is that the distrust is mutual. Researchers fear any form of institutionalisation because they have experienced what it may mutate into.

I acknowledge the conference audience’s scepticism about ethics committees. I am also sure that my personal experience of research into knowledge production in Russia does not qualify me to make generalisations. However, as an early career scholar, I have definitely benefited from a formal and structured reflection on the ethics of my interview-based research. With the help of a list of questions, I was able to think through potential dangers to research participants as well as to myself. And while there may be some artificiality to the process of coming up with ways to mitigate potential dangers – as the reality of the situation in the field is never exactly the same as the one that a researcher envisages beforehand – the formalisation of ethical assessment provided me with food for thought and, trivial as it may seem, made me allocate time for reflection on ethics.

Criticism of research ethics committees in English-language journals ranges from softer concerns about their lack of necessary expertise to warnings about their infringement of academic freedom. In Russia, where scholars are struggling not just with increasing bureaucracy but also, more recently, with political control, these clearly are worries that should not be dismissed. In addition, Russian scholars face a shortage of research funds and declining academic standards – exacerbated by the fraudulent awarding of academic titles, unfair practices in conducting and publishing research and a proliferation of low-quality journals.

Moreover, there are several instances where scholars’ own initiative and joint action has worked far better than the mechanisms of control designed by bureaucrats. For instance, in 2013, a group of researchers and journalists established Dissernet, a now widely known and respected community network aimed at raising awareness of and exposing fraud in the awarding of academic titles. Professional groups such as historians’ Free Historical Society and open access publishing outlets such as Troitskii Variant are another illustration of how scholars can organise to expose and resist unnecessary bureaucratic pressures. The former protests against many aspects of state interference in academia, such as the removalof the European University’s teaching licence and the criminal case against an academic researching Russia’s political system. The latter sees its mission as preventing the degradation of academic standards; contributors regularly comment on the government’s plans for academic reform, such as a presidential decree demanding a greater number of Russian-authored publications in the Web of Science.

Such sceptical attitudes towards the regulation of research mean that adopting models from elsewhere may not be the optimal solution in Russia. Scholars will need to think creatively about frameworks and principles that both experienced and early career researchers can draw on to help them with ethical challenges encountered in the field. A balanced analysis of both the positive and negative aspects of the mission and actual workings of research ethics committees would be a good starting point.

Katarzyna Kaczmarska is a Marie Curie research fellow in international politics at Aberystwyth University.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Paper weight

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?