The journalistic convention on metaphors dictates that big new buildings be described as “cathedral-like”. The convention can be upheld in the case of the UK’s National Automotive Innovation Centre, given not just its enormous scale but its wooden roof and Coventry location – especially on a day when the building is peaceful ahead of its scheduled opening later this year, while high windows bring in sunlight and blue sky.

The NAIC, on the University of Warwick’s campus as part of its WMG (Warwick Manufacturing Group), will house Jaguar Land Rover and Tata Motors’ most advanced research, alongside WMG researchers and students. The £150 million building – with lifts to take cars up to huge, LED-lit showrooms and privacy shutters to close off parts of the building when the research gets confidential – is billed as the largest private investment in any university in Europe, the largest automotive research and development facility in Europe and, potentially, the largest wooden roof in Europe (there might be a couple of bigger ones in Germany).

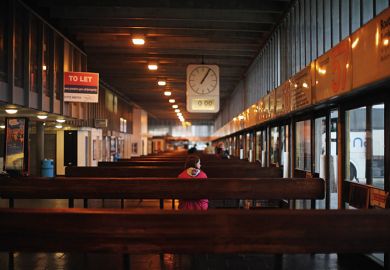

Warwick describes the NAIC (pictured below) as part of a drive to make Coventry, the birthplace of the British motor industry and seen by some as its graveyard, the “smart motor city” – a vision to position the city as a leader in the use of connected, autonomous and electric vehicles.

The NAIC is thus part of a pronounced civic turn for a Russell Group university that, partly as a result of its name and its location on the south-west edge of the city, has often been viewed as standing apart from Coventry (despite being founded by local councils and industry). Coventry University, based in the city centre, has traditionally been the more civic university.

Stuart Croft, who took over as Warwick’s vice-chancellor in 2016, said that the university is now “really trying to answer the question, ‘How does the University of Warwick benefit the citizens of Coventry?’ And I think that isn’t a question that we really asked a lot in the past.”

Warwick’s experience sheds light on how universities might help to address post-industrial decline – a policy priority given sharper urgency by the social fractures revealed in the UK’s Brexit vote – and support councils in the era of austerity.

Coventry is a city with impetus; it won the race to become the UK’s next City of Culture in 2021 and was named the UK’s European City of Sport in 2019. That might help to change attitudes to a city long unloved by outsiders. Earlier this year, YouGov polled more than 55,000 people on their opinions towards 57 English, Scottish and Welsh cities, producing a “popularity” ranking. Coventry was ranked 51st (Bradford was bottom).

But Coventry is now “a vibrant city – and it wasn’t vibrant a decade ago”, according to Martin Reeves, Coventry City Council’s chief executive. He sees a definite shift in Warwick’s attitude to the city in recent years and a new spirit of collaboration between the two universities, and between them and the city council. Professor Croft “and the [Warwick] governing body have made it a really clear strategic intent to get even closer not just to the city, but to those areas – including Canley [formerly the home suburb for many car workers in the city’s industrial heyday] – immediately around them that also need to see the benefit of having a world-class university literally cheek by jowl,” he said.

Mr Reeves, a governor at Coventry University, referred to the city benefiting from “the complementarity of two universities which aren’t competing, necessarily”, giving it a “competitive edge over other places not just in the UK, but across Europe as well”.

The city council was chosen as a partner, alongside WMG and the Coventry and Warwickshire Local Enterprise Partnership, in the £80 million National Battery Manufacturing Development Facility, after it won a national competition led by the Advanced Propulsion Centre, supported by Innovate UK.

The NBMDF is billed by Warwick as aiming to “assist manufacturers and boost the future vehicle and transportation electrification industry by leading innovation”, as well as including “a learning facility…to train the future skills base in all elements of battery manufacturing”.

Meanwhile, WMG researchers are working with the city council on plans for a “very light rail”, battery-operated, driverless transit system for Coventry.

WMG – an academic department of the university that has worked with companies on innovation in manufacturing since its foundation in 1980 – specialises in autonomous, connected vehicles. That was part of the reason the government made Coventry a testbed for 5G, the network that such vehicles will use.

Coventry’s two universities “can service skills and R&D at [the] top level” for the city’s employers – including big companies like Jaguar Land Rover (still headquartered in Coventry after being bought by India’s Tata Motors in 2008) and Eon, said Mr Reeves. But they can also do this “all the way through the supply chain” for the city’s “proliferation” of small and medium-sized firms in fields such as automotive and digital technology, he added.

Developments such as the NAIC and the battery centre can help to nurture an “eco-system…around autonomous, connected vehicles” which “potentially has got higher economic value [and] gives us more sustainability…than we once had just with automotive”, Mr Reeves said.

He also highlighted the “vast” spend on housing and retail from the two universities’ combined 60,000 students. And the fact that the universities “can keep us [attracting] inward investment adds that economic vitality”, he added.

But the fact that Coventry is now “vibrant” offers the universities “really powerful added value for recruitment and retention of students and academic staff”, so it has “cut both ways”, Mr Reeves said.

In national policy terms, the Brexit vote has belatedly focused minds on “left behind” or “held back” areas of the country. Has that been a factor in Warwick’s explicit civic turn?

Professor Croft noted that “everywhere around us voted Leave, except for Warwick district…where most of our students and staff live”.

He added that in his personal view “a lot of the referendum vote was about austerity” and “certainly in the city there’s a lot of anti-austerity feeling”.

Professor Croft continued: “One of the great fears for me is that, even though Coventry is really on the upswing…in a few years’ time, all local authorities’ budgets will be pared right to the bone…We have to preserve and support the civic heart of a city like Coventry, which is the city council.”

Universities do not provide core services to the general public – so there are limits on their ability to mitigate the impact of austerity on council budgets.

But the two Coventry universities were “the first to step up and support our very early ambitions for City of Culture when it was a long shot for us to even get shortlisted”, said Mr Reeves, putting not just financial support but “their volunteering body, their academic body, right into the heart” of the bid.

Professor Croft said that while winning the City of Culture bid was an “amazing thing”, the reaction outside the city was largely “dispiriting”. He lamented that “a certain piece of music by The Specials in a certain year comes back again and again and again”. The Coventry band’s 1981 number one Ghost Town is seen as a critique of Thatcher-era deindustrialisation, with particular reference to their home city.

Professor Croft hopes that the City of Culture accolade will bring a tourism “boom” (where else can you see a modernist city centre juxtaposed with medieval remnants, plus a cathedral that is perhaps Britain’s ultimate symbol of post-Second World War rebirth?) and transform perceptions of the city. If that happens, Coventry’s two universities will have played a part as supporters of the bid.

Another key part of the jigsaw is creating apprenticeship opportunities, said Lord Bhattacharyya, chairman and founder of WMG.

A WMG Degree Apprenticeship Centre is scheduled to open in 2019. Across the university, there is a target to have 10 per cent of undergraduates on degree apprenticeships by 2026.

Professor Croft said that a new social work degree apprenticeship is already oversubscribed. Apprenticeships bring a “positive impact for people in our region”, bring the university closer to companies and make Warwick “slightly distinctive in relation to other Russell Group universities”, he argued.

Warwick could plot a future of global prestige without paying much attention to Coventry. Why does it need to connect with the city?

Mr Reeves highlighted that research assessment now puts great stress on “industry translation, from the great things that will go inside things like the NAIC, the battery plant. And translation into business and industry requires connection to a local, vibrant city.”

And in social policy and social impact, the university has “got a living lab” in the city “where they can test some of this stuff”. Mr Reeves added that “being globally connected and at the same time anchored in the local area is not just, in my view, the right thing for universities to do, it actually makes good academic, research and business sense for them as well”.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Going local: institution reanchors itself in city

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?