Some new universities are better than a number of research-intensive institutions at "adding value" for students by consistently helping them to get well-paid jobs, an analysis has found.

The study by international consultants The Parthenon Group suggests that subject mix and location have more influence on starting salaries than prestige for institutions outside the elite's upper echelons.

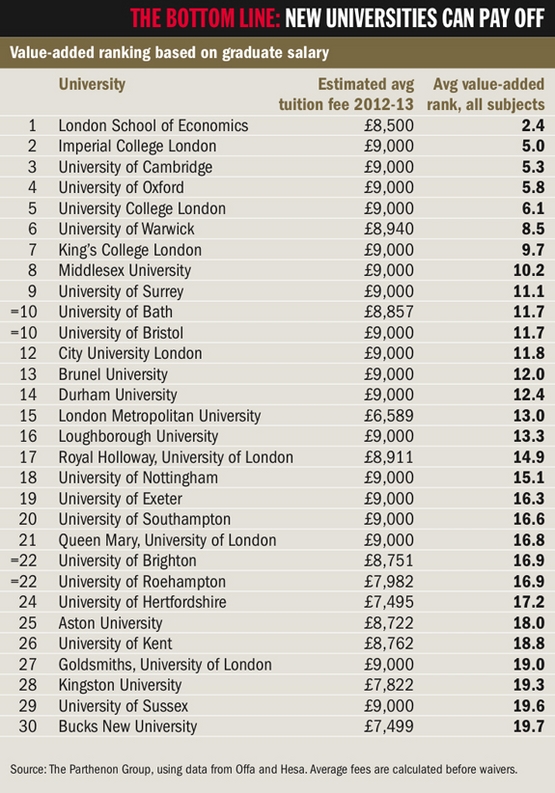

Although a high "salary premium" is still earned by those attending the most selective universities, some post-1992 institutions do just as well as or better than many Russell Group institutions on employment outcomes. Among them are Middlesex University and London Metropolitan University, which both come in the top half of a league table of the 30 "highest-value universities" compiled by Parthenon.

The results will be seen as a surprise in some quarters and are likely to fuel debate about the relative quality of different institutions in light of the tuition fees they are set to charge undergraduates in 2012-13.

They could also lead to the government taking a closer interest in which universities are drawing more heavily on Treasury funds through student loans (see box below right).

Parthenon, which advises clients including US for-profit providers, compiled its table using data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency on the qualifications used by students to enter university and the salaries they earned six months after graduating.

Institutions were ranked on graduate salary across a range of courses and their average rank calculated to provide a snapshot of the best performers at different levels of the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service tariff. An overall league table was then compiled to show the universities consistently towards the top of the average salary rankings.

Let's get down to business

Matt Robb, senior principal at Parthenon, said the analysis did come with some "health warnings", such as the fact that it does not account for the number of graduates not in work after six months.

However, he said, it shows that universities feeding into the London labour market - but also focusing on subjects with strong employability outcomes - had a distinct advantage.

"Status is clearly still a factor in terms of salary for the elite institutions such as Oxford or Cambridge, but once you get past roughly the top 10 to 15 institutions the picture becomes more mixed," he said.

He added that any institution outside the 10-15 bracket would need to take a "detailed look" at the subjects they offered, especially given that higher fees would only increase the importance of employment to student choices.

Besides London Met and Middlesex, other post-92s in the top 30 include the University of Roehampton, Bucks New University and the universities of Brighton and Hertfordshire.

Many were benefiting from offering business-related courses or subjects such as IT and science-related disciplines whose graduates were in demand from employers, Mr Robb said.

Malcolm Gillies, vice-chancellor of London Met, said the analysis was "useful" as it was "important that we see what (subject) areas have good career outcomes".

However, he cautioned that six-month salary data did not reflect the fact that large salaries came later in some careers.

Christopher Snowden, vice-chancellor of the University of Surrey, which came ninth in the league table, said Parthenon's findings were "no surprise" and reflected his institution's focus on employability. But he added that while the choice of subject mix was important, a university's general preparation of students for the world of work was also crucial.

Professor Snowden said: "In employer surveys, a lot of the time subject is ranked below third place...They are often looking for other qualities."

He added that it would be wrong if universities, after viewing such a league table, abandoned subjects of "national importance" such as nursing in favour of those that produced the best-paid graduates.

Sally Hunt, general secretary of the University and College Union, said the analysis risked contributing to a "fast food" vision of higher education.

"Universities are not just graduate factories turning out a ready supply (of employees) for business - they are there to teach a diversity of academic subjects for a wide range of purposes that serve all our communities," she said.

Salary data may offer state backdoor route to lower fees

The "value-added" analysis carried out by The Parthenon Group could have "profound" implications for how the government subsidises student loans, it has been suggested.

It is already known that ministers are interested in whether data from the Student Loans Company could be used to show which institutions and courses cost the taxpayer more in terms of how quickly graduates pay off debt.

Some academics have suggested that if these data were robust, the government could use them to ensure that universities with poor graduate employment records did not charge tuition fees near the top limit.

Matt Robb, senior principal at Parthenon, said its study of which universities consistently scored better on graduate salaries would begin to show the types of subject and institution whose students were less likely to repay loans.

"For certain subjects and institutions, university costs will likely never be paid back by the majority of students," he said, adding that universities in the North of England tended to fare particularly badly owing to their location in more depressed labour markets.

"This has profound implications politically because it quite clearly shows that to an extent the student loans system is a kind of regional development fund," he said.

However, Andy Westwood, chief executive of GuildHE, said it would be wrong to penalise universities simply because they were located in weak local economies.

"I think that would be unfair. If you've got a weak local labour market and a weak local economy, then my view would be that a university would absolutely be one of the things that you need there," he said.

He added that the study may simply be reflecting regional variations in salary levels rather than the relative performance of different institutions in preparing students for the world of work.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?