Research is so underfunded in the UK that overseas students are in effect subsidising it through their fees to the tune of £8,000 each, according to a Higher Education Policy Institute report.

The eye-catching finding is from a report that shines fresh light on the surpluses from student fees that are used to fund research at UK universities, including previously unpublished data about varying levels of cross-subsidy at different universities.

The study says that, despite attempts over several years to deal with the fact that research is not fully funded by grants from public funders and charities, the losses being made by research seem to be getting worse.

As a result, the report calls for urgent action in the government’s autumn Budget on 22 November to close the estimated £3.3 billion deficit in research funding, which it says means that £1 in £7 spent on research comes from surpluses made from teaching.

The report – How much is too much? Cross-subsidies from teaching to research in British universities – highlights data already in the public domain from the UK’s Transparent Approach to Costing initiative. This shows that teaching UK and European students generates a small surplus of about £200 million across the sector (although this masks large cross-subsidies from some subjects to others).

However, the teaching of overseas students is the main source of cross-subsidy for research, offering a surplus of roughly £1.8 billion. The study calculates that £3,800 of the average annual tuition fee paid by international students goes to funding research, which is more than £8,000 over the course of an average degree.

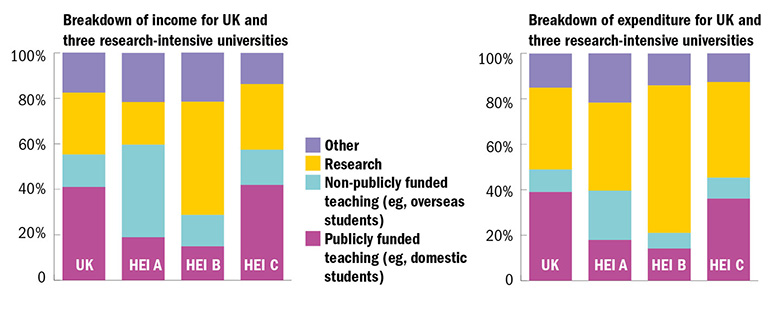

The report also contains new figures from three unnamed research-intensive universities showing how overseas students at some institutions are propping up research activity by an even greater amount.

At one of the universities, less than half the full costs of research are recovered, while two of the three institutions make a return on overseas students that is almost double the cost of teaching them (see graphs).

Cash flow: income sources

Source: Trac data 2014-15 and private data. HEI C data are for 2015-16.

Vicky Olive, a postgraduate economics student at the University of Oxford, who compiled the report, said that she thought international students would be surprised by the findings.

“International students know that they pay above cost price to study in the UK, but not what their fees pay for,” she said.

“Most would be shocked to find out how much goes towards funding research, although students prefer that their money funds research rather than bureaucracy within their university.”

She added that key to the debate was more transparency on cross-subsidies as students may not be “averse” to a proportion of fees going towards research “so long as it filters through to teaching quality”.

Hepi director Nick Hillman said that while some cross-subsidies were “inevitable, even desirable” in UK higher education, the transfer from teaching to research “looks less sustainable than it did”, especially given the heightened focus on tuition fees and whether they should be lowered for domestic students.

The report also contains an analysis of which funding sources are better at covering the full costs of research, which include not only the “directly incurred” costs such as staff and equipment used specifically for a project, but also the cost of shared equipment and staff and even less tangible elements such as the use of central library facilities and administrative services.

The analysis highlights how research councils and other government funders contribute on average more than 70 per cent of the full costs of research, but for European Union funding this figure falls to 65 per cent and for funding from charities just 60 per cent.

It says that, for the government to meet its target of increasing spending on research development in the UK to 3 per cent of GDP, a total of £6.3 billion a year extra would be needed, including from the charity sector. The report calls for the government to announce an extra £1 billion for research in this month’s budget and for suppport to ease the deficit on charity funding.

In a foreword to the report, David Coombe, director of research at the London School of Economics, calls for funders to meet the full cost of research and says that the trend for matched-funding schemes was exacerbating the issue.

“The problem is not only in the volume of funding; it is the practice of research funders to demand more than they are willing to pay for,” he writes.

“Institutions have no real choice but to accept the terms offered. Few can turn down grants which serve their missions and enhance their reputations. But as every [university] finance director knows, with each grant comes yet further strain on already-stretched institutional research infrastructure.”

Phil McNaull, director of finance at the University of Edinburgh and chair of the British Universities Finance Directors Group, said the government “must accept” that if it could not meet the full cost of research through grants, institutions should be able to cross-subsidise from teaching or other sources.

“The government could help by recognising the important contribution from overseas fees to the portfolio of funds required to support research activity in universities.

“Practical steps could include removing overseas students from net immigration targets and scaling back efforts to break up the cross-funding activities of universities through selective focus on tuition fees.”

simon.baker@timeshighereducation.com

Opinion: Cross your subsidies and hope not to die

The picture in Australia: data suggest research underfunding not just a UK problem

The UK is by no means the only major research nation to struggle with meeting the full costs of carrying out scholarship.

Figures quoted in the Higher Education Policy Institute’s report on cross-subsidies suggest that surpluses from teaching have been even more important in funding research in Australia.

It says that, according to research by the Grattan Institute, for every A$5 spent on research in the country, A$1 comes from money made on teaching, a level of cross subsidy that increased six percentage points from 2008 to 2012.

However, unlike the UK, in Australia much of this teaching surplus has also come from publicly funded domestic students: the Grattan Institute estimates that as much as A$1.5 billion (£877 million) a year has been generated from this source in the past.

Andrew Norton, higher education programme director at the Grattan Institute, said that government reforms struggling to pass the country’s Senate contained elements that might ease the pressure on research funding.

But he added that the notion of a “cross-subsidy” from student fees was more contested in Australia, as the main domestic government funding scheme for students had traditionally also been seen by many as money for research too.

Mr Norton also pointed out that while international students contributed a lot to research funding, they often “want to study at a prestigious university, and prestige is heavily influenced by research.

“So they are getting what they are paying for through the status of their degree, rather than direct spending on students.”

Meanwhile, a comparison in the Hepi report between the two most populous nations of the UK also highlights how the research deficit is smaller in Scotland: 23 per cent of research income against 40 per cent in England.

However, due to Scottish and continental European Union students paying no tuition fees, the Scottish sector also makes a deficit on publicly funded teaching of 6 per cent as opposed to the small surplus in England.

Assuming that this deficit is filled by cross-subsidising the large surplus from teaching international students, the report says that overseas fees only fund research in Scotland to the tune of £57 million, or 4 per cent of costs, as opposed to 14 per cent in English universities.

Simon Baker

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?