Part-time academics in UK universities are working double the hours that they get paid for, according to a study that warns that casualisation brings “shame” to the sector.

Data on 1,568 part-time teaching staff, collected in a survey by the University and College Union and published on 4 July, showed that respondents were contracted to work for a mean average of 14 and a half hours per week. However, because their contracted hours did not allow enough time for preparation, marking and other activities, they estimated that they actually worked 26 hours – meaning that 11 and a half hours, or 44.6 per cent of their working time, was unpaid. On the median average, half of part-time staff’s labour was unpaid.

In effect, the UCU said, this meant that the hourly rate of pay for part-time academics was radically lower than their on-paper salary and was, in many cases, dangerously close to the minimum wage. For example, a part-time lecturer contracted to work 10 hours a week at a rate of £18.70 an hour who actually puts in 20 hours’ work would be earning £9.35 an hour in reality.

Jane Thompson, a bargaining and negotiations official at the UCU, said: “Employers need to recognise the full cost of providing teaching and stop trying to provide these services on the cheap, at a cost to both staff and students.”

About 27,500 people, including academics and some support staff, were employed by universities on zero-hours contracts last year, according to data released by the Higher Education Statistics Agency. More than a third (38 per cent) of all part-time academics were on hourly paid contracts, the figures showed, while one in three academics was on a fixed-term contract.

The UCU data on hourly pay were drawn from a wider survey of 3,802 “casualised” higher education staff, which found that 84.6 per cent of respondents had considered leaving the sector, with lack of job security being the main motivation. More than four out of five said that their contractual status made it hard to make long-term family plans (82.6 per cent) or financial commitments (83.2 per cent), and nearly half (48.5 per cent) held at least one additional job in the sector in order to make ends meet.

One respondent said that they lived “in limbo”. “[Universities] know we’re desperate, and they use us. I look like a crazy person on any financial applications. I have a minimum of three jobs at any one time, and I never know what or when I’m getting paid,” the person said.

Seventy-one per cent of respondents said their mental health had been affected by the stress of working on an insecure contract, with 43 per cent reporting an impact on their physical health.

Another respondent claimed that they were “tired, depressed and struggl[ing] to cope”. “I worry constantly what will happen if I am sick or don’t manage to find enough work. Sometimes the casual work which is offered gets taken in less than a minute, so I end up constantly checking my emails and afraid to leave my computer to get a drink or go to the loo in case I miss the email,” the academic said.

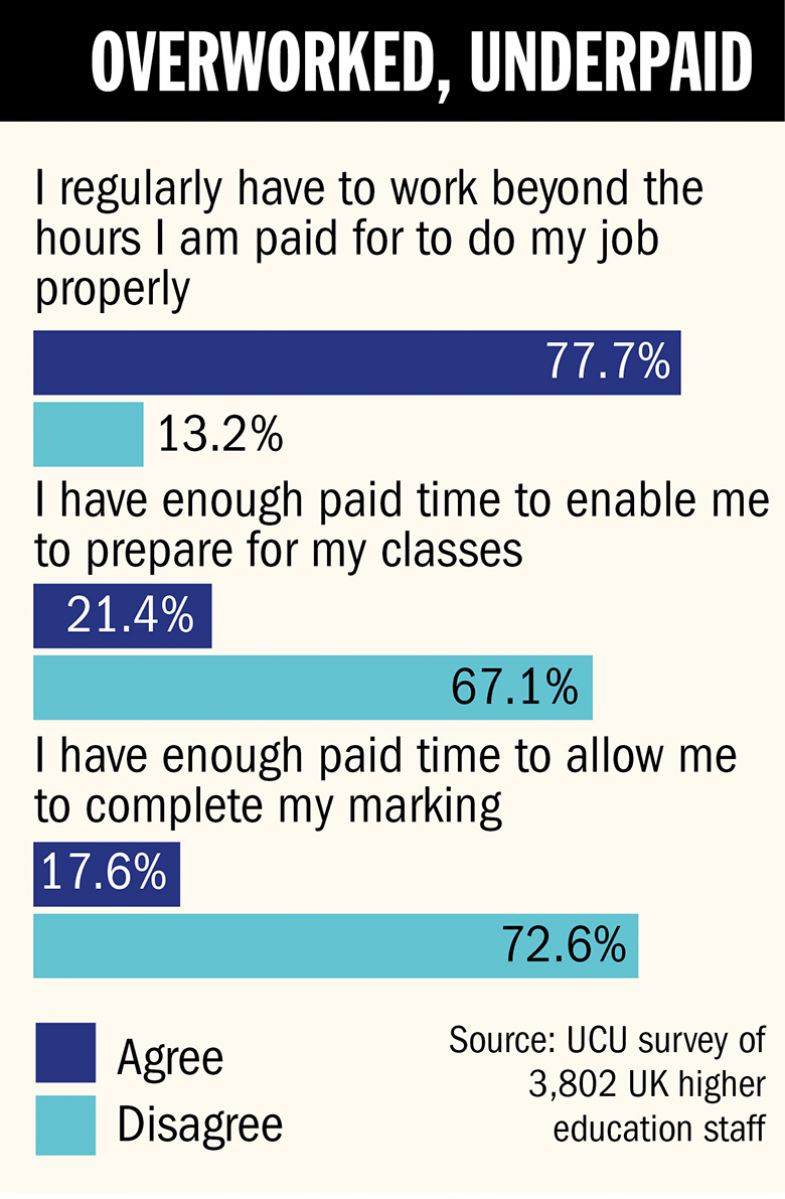

Some academics complained that they were paid only for the actual delivery of teaching hours. Respondents said that they did not have enough paid time to prepare for their classes (67.1 per cent agreed), keep in touch with the latest scholarship (75.3 per cent) or give students the attention and feedback they needed (71 per cent).

Marking was a particular problem – 72.6 per cent said they did not have enough time for this – with several respondents pointing out that although they were paid to mark assignments at the rate of three an hour, it could take up to an hour to grade one script and draft feedback.

All this had a knock-on effect on academics’ ability to build a research profile, with 80.9 per cent saying their own scholarship had been damaged by their having to work on short-term contracts.

Jo Grady, the UCU’s general secretary-elect, said universities were “digging the grave of the sector” if they did not address the problem of casualisation. The survey results were released as the union announced fresh ballots for industrial action over pay and pensions, to be held through September and October.

The report recommends that the Office for Students require English universities to publish figures on the proportion of teaching being done by hourly paid staff, and that research councils make employment of staff on open-ended contracts a condition of research grants.

The Universities and Colleges Employers’ Association said the UCU report “points to some important concerns”, which are “taken seriously by individual universities, with many reviewing the operation of arrangements for their hourly paid colleagues”.

“Universities always want to ensure their colleagues, whatever contract they are on, feel that they are appropriately rewarded and supported to give their best for students.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Some academics ‘work twice the hours they are paid for’

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?