Why are some societies made up of hunter-gatherers, and others farmers? Why do some believe in vengeful gods and others don’t? And what can explain why one group lives in relative freedom, and another under the whip of a tyrant?

The search for fundamental factors or rules that explain why societies develop in particular ways has exercised historians, political philosophers and anthropologists for centuries. Karl Marx made the case for technology being a key determinant, writing that “the hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill society with the industrial capitalist”. Over a century later, the polymath academic Jared Diamond argued in his book Guns, Germs, and Steel that lucky access to certain grains and domesticable animals not found in the Americas helps explain the historical dominance of European societies.

But neither of these thinkers had access to D-PLACE (the Database of Places, Language, Culture and Environment), a new publicly available database cataloguing over 1,400 societies, ranging from the Inuit of Baffin Island in remotest Canada to the !Kung tribe who hunt for food in the Kalahari Desert.

Crucially, the project pulls together information on culture, environment and language from previously incompatible anthropological databases so that researchers can at last statistically test, say, whether hunter-gatherer societies are more egalitarian, as anthropologists have long suspected.

“That’s the cool next step,” says Fiona Jordan, a senior lecturer in anthropology at the University of Bristol and one of the project leads. “We can now quantify it.”

For example, anthropologists have often wondered why there is more linguistic diversity around the Equator, she explains. With D-PLACE, researchers can test whether lots of valleys cause the emergence of so many languages or whether some other environmental feature is responsible. Previously, anthropologists had been able to address these questions only in an ad hoc, non-statistical way, Jordan adds.

The tool, whose development involved academics from Australia, the US, UK, Germany, Canada, New Zealand and Argentina, is already yielding some remarkable insights.

“The ecology of religious beliefs”, a paper published in late 2014 by the journal PNAS, used D-PLACE before it was made publicly available, to crunch data on nearly 600 societies to find out what factors explain a belief in “moralising high gods”, widespread in Europe and the Middle East but lacking in sub-Saharan Africa and South America, where atheism or a belief in spirits is more common.

The authors found that a belief in angry or benevolent deities was far more likely to emerge when people lived in harsh environments prone to ecological disasters, possibly because this reduced anxiety in the face of daily threats from nature. Moralising gods also appeared more frequently in societies with rights to movable property and higher levels of political complexity.

But the researchers also found that cultural inheritance seemed to play a role, as did the religion of neighbouring tribes. “The emerging picture is neither one of pure cultural transmission nor of simple ecological determinism, but rather a complex mixture of social, cultural, and environmental influences,” they concluded.

This shows how the statistical insights of D-PLACE can help anthropologists and historians move past the “hugely rancorous debates” about whether societies inherit their structure and culture from history, or whether they are ultimately shaped by geography, says Michael Gavin, one of the paper’s authors and an assistant professor in the department of human dimensions of natural resources at Colorado State University.

“I’m hoping that overall it will allow us to realise that both play a role,” he says.

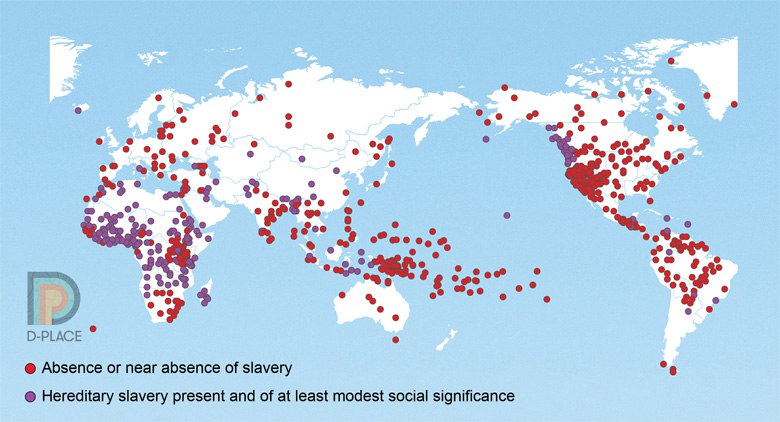

With so many variables in the database – from the prevalence of slavery to how far tribes live from the sea – there are now an almost limitless number of avenues for researchers to go down, looking for links between myriad different aspects of culture, language and geography. One project is currently exploring what factors influence whether societies allow people to marry their cousins, says Jordan.

The tool also makes statistical analysis all but instantaneous. Jordan says it is “magic” to be able to create world maps of linguistic or culture patterns “with a few clicks”.

“I joke to people that I could do my PhD in three months because I don’t have to plot these now by hand,” she adds.

She says that the depth of data even allows anthropologists to “play God” and project backwards in time to calculate how groups might have lived centuries before they were actually observed in a technique Jordan calls “virtual archaeology”.

But one question for researchers who use D-PLACE is whether any insights gleaned actually apply to post-industrial societies. Most of the societies included in the database are rural, says Jordan, and the vast majority were observed before 1950.

So when anthropologists make a discovery, such as the link between a belief in moralising gods and dangerous environments, this is not based on observations of the place where the majority of humans now live: the 21st-century city.

Gavin says conclusions from D-PLACE are still applicable to the modern world, even if they are not based on studies of post-industrial society. “There are patterns in history that we can learn from,” he says.

But Jordan seems less sanguine. Although there are anthropologists studying modern societies, for instance looking at societal behaviour in "tennis clubs, on Wall Street”, anthropology has taken a qualitative turn, so findings have not been fed into the categorisations that underpin D-PLACE, she says.

Either way, academics, schools and interested members of the public now have access to a vast encyclopaedia and atlas of human life. What is to be found there will become apparent in coming years.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Anthropology atlas opens new vistas

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?