On the day the 2018 World University Rankings were announced, notable figures in higher education met to discuss the way forward for international research partnerships

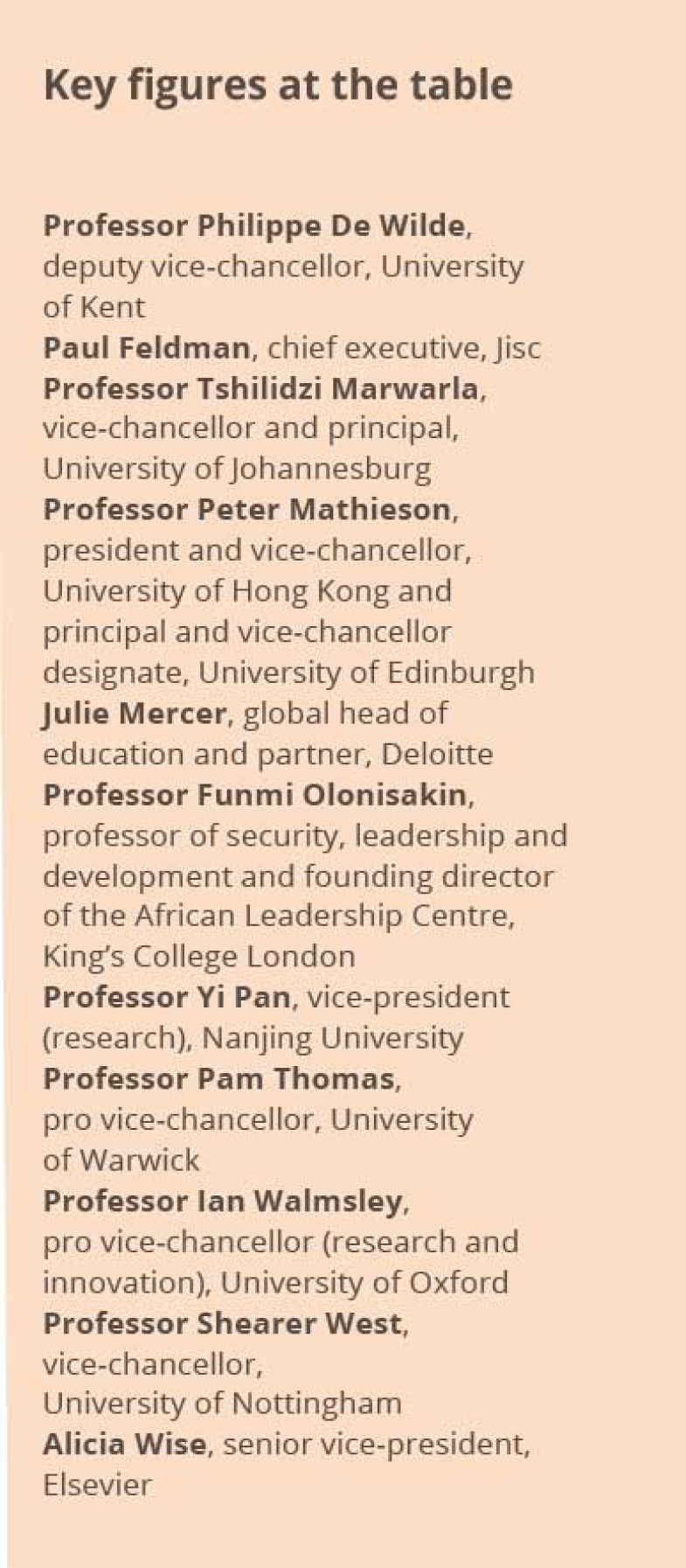

A roundtable organised by Times Higher Education in association with Jisc, the UK body for digital technology and resources in higher education, asked experts to consider the future of research collaborations against the backdrop of Western populism and shifts in global power structures. Professor Peter Mathieson, president and vice-chancellor of the University of Hong Kong, argued that the UK and Europe were becoming “less and less relevant,” with the higher education institutions of both facing an “existential challenge” regarding their dominance in research and teaching.

“While populism may be sad for you, it is not entirely sad for us,” said Professor Tshilidzi Marwarla, vice-chancellor and principal at the University of Johannesburg, describing how political fragmentation in the West is driving more student traffic within Africa, as well as greater collaborations between African institutions.

“Many of our students used to go to North America and Europe, but more are heading now to China and Japan for postgraduate study,” he said, describing the West’s predicament as “a good opportunity to expand the diversity of the system”.

Given that Africa’s population growth is predicted to double in size by 2050, and with many Asian nations investing a far higher percentage of their GDP in universities than their Western counterparts, how long can British and American institutions realistically maintain their dominance?

“It’s fair to say Africa won’t lead research growth anytime soon but the UK and US need to engage with Africa, understand their problems, and how Africa can help them, else Europe and other places will run the risk of being left behind,” said Professor Mathieson, who takes up the role of vice-chancellor at the University of Edinburgh next year.

“The same is true of Asia,” he said, pointing not only to the scale but also the “brilliant ability” that both possess. “If we don’t engage, we will be left behind.”

For Professor Shearer West, vice-chancellor designate of the University of Nottingham, the rise in anti-expert culture across the Anglo-American world was the most worrying aspect of populism in the West. “It’s completely in contrast to what I see in Asia and other parts of the world, which are so very proexpert and pro-education,” she said.

“If we begin to pull apart in those ways then we’re in real trouble.”

Integral to any issue in higher education is finance. With the UK facing the potential loss of European Research Council funding, could there be a global council created for the world, charged with bringing together research on a global scale?

Professor Pam Thomas, pro vice-chancellor at the University of Warwick, agreed that while it would be a “wonderful ambition”, the idea of producing anything on a global scale was “incredibly challenging”.

She argued that there would need to be a first stage following Brexit, which involved getting bipartite funding relationships up and running.

“Multilateral funding has put Europe at the forefront of the research agenda,” said Professor Ian Walmsley, pro vice-chancellor for research and innovation at the University of Oxford, where half of all institutional research outputs are published with academic and industry partners outside of the UK.

“Most research collaborations are under the radar,” he said, stating that the threat to UK universities’ research collaborations in the future “may reflect itself around immigration quotas; our ability to exchange people”.

“Students are still within the immigration cap,” he said. “Training students, bringing them together, is a key part of projects [that would] potentially be challenging.”

Paul Feldman, chief executive of Jisc, said that many disciplines were already operating on a global basis.

“Disciplines such as astrophysics and particle physics have already worked out that they need to ignore national boundaries in terms of the work they do,” he said. Pointing to

the European open science cloud as an example of a big multilateral collaboration that enables other non-European nations to participate was a recognition by Europe, he said, that they “have a unique role to play in delivering projects with a multinational capability, in a way that allows global collaboration”.

He argued that it was “inconceivable” that Europe would not want continued collaborations with UK researchers, but admitted that it was hard to see how they could do that in a Brexit context without making the research framework programme global.

“But that will only happen if researchers act to make it happen. It won’t happen passively,” he said.

When it comes to European funding, “we can’t have it as good as we did”, said Professor Funmi Olonisakin, of King’s College London.

As research councils will have to shift the forms of collaboration that they forge in the future, “it matters that there are those not around the table having this conversation”,

she said. Professor Olonisakin called for a “truly global conversation” to take place so that any new funding arrangements wouldn’t just continue to “reinforce the power

dynamics of the status quo”, but would allow “new forms of funding with future power holders”.