Source: David Lyttleton

Despite years of promoting employability on undergraduate courses, a first degree is no longer enough to secure a decent job for many graduates

“I feel guilty for finding it all so interesting,” a student on a taught master’s in history told me recently. My surprise must have been palpable because she went on to explain: “It’s just with the expense of it all, you have to tell people you’re doing it to get a job; otherwise it seems like an indulgence, really.”

The idea that postgraduate education is primarily concerned with future employability is a creeping orthodoxy. Sadly, it seems that these days very few postgraduate students are happy to admit they are driven solely by a love of their subject and a desire to learn more. The results of the latest Postgraduate Taught Experience Survey make it very clear that students’ motivations for undertaking postgraduate study are dominated by the thought of their future job prospects: just 25 per cent say they are motivated only by an interest in their subject.

Students have always had individual and often instrumental desires for pursuing further study, but what concerns me is the way universities today so often aim to meet, rather than challenge, such motivations.

Postgraduate courses are, of course, big business for UK universities and have provided institutions with an increasing source of revenue over at least the past two decades. In recent years, the cap on the number of undergraduate students that universities are allowed to admit, combined with the removal of the block teaching grant, has led many institutions to focus recruitment on fee-paying postgraduates who can be enrolled in unlimited numbers and at any price the market will sustain. As a recent survey published in these pages reported, fees for taught postgraduate courses now range from £3,400 to £,552, and costs are substantially higher than this for students on some highly specialised master’s programmes.

Factors that may have driven up postgraduate fees include the threatened withdrawal of Higher Education Funding Council for England funding for taught postgraduate provision, the rise in undergraduate tuition fees and a decline in the number of overseas students. At the same time, research councils have decided to stop providing financial support to students on taught master’s programmes, and postgraduate students cannot access Student Loans Company help for either tuition fees or living expenses. Postgraduate students are forced to make private arrangements to fund their education and are usually dependent upon some combination of commercial loans, family support, institutional bursaries and earned income. The need to have access to private finance has prompted much discussion about growing social inequalities in access to postgraduate provision.

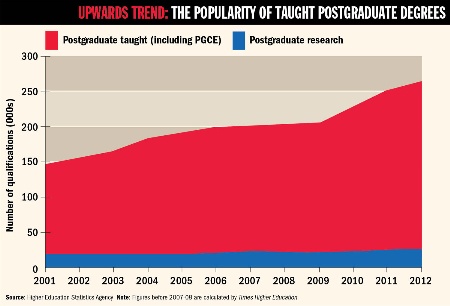

There is concern that this triple whammy of higher fees, lack of finance and declining numbers of overseas students will have an impact upon recruitment to postgraduate courses. In the 2011-12 academic year there were 568,505 students registered on postgraduate-level courses, over one-fifth of all students according to data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency. This represents a fall of 3.4 per cent on the previous year’s figures. However, viewed over a longer period of time, the rapid increase in the numbers of postgraduate students has been unprecedented. A parliamentary briefing paper reports that in 1990, 31,324 students at UK universities were awarded higher degrees; 10 years later this had risen to 86,535; and by 2010 the number had increased to 182,610.

Ever-increasing levels of personal debt, combined with an uncertain labour market, no doubt contribute to the perception among individual students that postgraduate study needs to enhance their employment prospects, and this may well be reflected in the specific form the expansion of postgraduate education has taken: the increase has almost all come in recruitment to taught courses as opposed to supervised research programmes. The numbers of qualifications obtained on taught postgraduate programmes grew from more than 180,000 in the academic year 2007-08 to more than 240,000 in 2011-12. But over the same period the numbers doing postgraduate research degrees stayed roughly the same at around 25,000 a year. This may indicate that growth is less about students pursuing cutting-edge research and an academic apprenticeship than it is about gaining the qualifications necessary to secure any career. It is interesting to note that the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, with their more traditional academic and research-focused postgraduate courses, are seeing less growth in this area than the likes of the universities of Buckingham and Bedford, which offer more vocationally oriented and structured provision. The drive towards vocationalism is further reflected in the taught courses students are opting to take: in the 2011-12 academic year the number of postgraduates on programmes in business and administrative studies exceeded 110,000. There were more than 90,000 education postgraduates and more than 50,000 students on courses allied to medicine.

When academic skills such as criticality are downplayed, the role of lecturer risks becoming reduced to that of trainer

Universities now consistently promote further study on the basis of enhanced career prospects, but whether this constructs or responds to students’ instrumental motivations is debatable. Institutions, in turn, take their lead from government. The 2010 government commissioned review, One Step Beyond: Making the Most of Postgraduate Education, describes the benefits of postgraduate study entirely in terms of employment prospects and wage differentials: “Postgraduates are highly employable and on average earn more than individuals whose highest qualification is an undergraduate degree.” Similarly, the 2010 Browne review of higher education funding and student finance specifically linked the payment of postgraduate fees to students’ future employment prospects (“private benefits to individuals would be sufficient to generate investment”). Universities market their courses in the same terms. De Montfort University advises potential students to “join the 96 per cent of our UK postgraduate students who are in further education or employment within six months of completing their course, earning an average starting salary of over £35.5K”. Swansea University claims: “The skills and qualities you develop during your master’s degree will enhance your CV and help you stand out in a highly competitive graduate employment job market.” Note the implicit acknowledgement that despite years of promoting employability on undergraduate courses, a first degree is no longer enough to secure a decent job for many graduates. Instead, the bar has simply been raised and entry qualifications for many professions are now notably higher than they were a decade ago.

A new trend is for universities to promote the opportunities for paid employment during postgraduate study. Enrolment on a full-time course does not necessarily equate to being a full-time student. Many self-funding students are choosing to combine full-time study with part-time work rather than the other way round. A 2007 study reported in the Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Education, for example, claims that 62 per cent of UK students on full-time master’s courses work part-time. Some may feel they have little alternative and it often makes financial sense to study full-time and work part-time: one year’s full-time postgraduate tuition fees may be cheaper than two or three years of part-time fees.

Many universities now play an active role in helping postgraduate students to find paid work. The University of Hull acknowledges: “Many full-time students also work part-time,” and Loughborough University’s website advises potential postgraduates: “One way of supplementing your income is to take a part-time or temporary job while studying.” It goes on to provide a link to employment opportunities on campus. This could be seen as simply a pragmatic attempt by universities to secure their “customers” and income streams irrespective of the quality of the individual student’s educational experience. But there is more to it. When a postgraduate qualification is undertaken primarily with a view to securing employment and higher earnings it makes sense to gain work experience in employment rather than in a seminar room. Durham University’s web pages for postgraduate students claim: “Part-time work while you’re at university isn’t only a good way to help pay for your studies, it’s also a very valuable aspect to add to a CV and a great way to gain the skills future employers are looking for.” In this way, picking up “soft skills” through employment is becoming an important part of the postgraduate student experience.

Meanwhile, the nature of some of the postgraduate courses now on offer clearly demonstrates the blurring of boundaries between education and training. The University of Wolverhampton’s business school, like many others, offers master’s-level courses in a range of topics directly relevant to the world of work, from an MA in coaching and mentoring to a postgraduate certificate in employability and enterprise. Middlesex University offers a one-year course leading to a professional doctorate by public works, part of which seeks to credentialise what people have already achieved in employment. It is described as being “open to all professional areas as the focus is defined by the candidate’s particular work context and area of activity and their own unique area of interest. This may be located within a profession or sector, or may be more individual in nature.” Students are assessed on their ability to reflect upon what they have achieved in the labour market rather than their ability to master, interpret and add to any body of knowledge, research or scholarship.

More emphasis is also being placed on the general employment skills that might be gained via more traditional academic postgraduate courses. Students taking a master’s degree in chemistry at the University of Glasgow, for example, are told that the course will help them to develop transferable skills in project management and team working, preparing and presenting oral and poster presentations and problem-solving. At the University of Manchester, students studying for an MSc in the School of Earth, Atmospheric and Environmental Science are advised that they will be taught a wide range of transferable skills “including numeracy, communication skills, workload and research planning [and] problem solving”. This trend worries me: when academic skills such as criticality are downplayed, the role of the lecturer risks becoming reduced to that of trainer.

Overall, it is clear that a fundamental shift has taken place in postgraduate education away from intellectual endeavour and towards the vocational and the general. This could be highly damaging for universities. They must guard against simply confirming what students can already do, or they will be reduced to administering certificates. Academics will also fundamentally fail postgraduate students if they do not help them to think outside their existing frames of reference by confronting new ideas and knowledge. While mounting student debt may make employability a growing concern, the first duty of universities is to provide an education that challenges and inspires, and an education that is truly worth paying for. No student should feel that learning for its own sake is an indulgence.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?