“Right now my students see two options,” says Mark Edmundson: “Smoke a lot of weed or go to law school.”

One choice means “going to university, getting a good job and having a family, and striving in a middle-class way – and I participate in that life”. The other means “saying, ‘Screw it all!’ and trying to enjoy yourself as much as you can – and I respect that, too”. Yet his new book, Self and Soul: A Defense of Ideals, is an attempt to “provide a sense of a third option”.

Now university professor of English at the University of Virginia, Edmundson has long been viewed as an exceptionally stimulating and wide-ranging cultural commentator, often drawing on his own life. He has written books about the conflict between poetry and philosophy and the last phase of Freud’s life, but also about what he learned from a particularly charismatic schoolteacher, from American football and from “the kings of rock and roll”.

In Nightmare on Main Street: Angels, Sadomasochism, and the Culture of Gothic, published in 1997, Edmundson explored how “horror plays a central role in American culture. A time of anxiety, dread about the future, the fin de siècle teems with works of Gothic terror and also with their defensive antidotes, works that summon up, then cavalierly dismiss, Gothic fears.” The book has explicitly personal roots in the fact that “several years ago, for no reason I readily discerned, I began watching horror movies...What was I doing teaching Shelley’s rhapsodic Ode to the West Wind by day, then by night repairing to the VCR to watch Texas Chain Saw Massacre 2?”

It goes on to build striking links between high culture and vast tracts of popular culture, from vampire novels and daytime television to media coverage of the O. J. Simpson trial. It also includes an intriguing digression on the presence of Gothic motifs in much “contemporary intellectual analysis”, where power and patriarchy are sometimes treated like ghosts that just keep on popping up, possessed of “a supernatural vitality and resourcefulness that makes it virtually impossible to defeat” them.

But Edmundson has also produced broader polemics on higher education. In Why Read? (2005), he regrets that “universities have become sites not for human transformation but for training and for entertaining”. He also describes how “critical thinking” often amounts to “the art of using terms one does not believe in (Foucault’s, Marx’s) to debunk worldviews that one does not wish to be challenged by”. Far from being radical, it helps develop “instrumental reason” and so provides “good preparation for doing work in a corporation in which you look only at means and not at ends”.

In last year’s Why Teach?: In Defense of a Real Education, Edmundson goes even further. Books by professors of literature may be “full of learning, hard work, honesty and intelligence that sometimes in its way touches brilliance”, but they are also, unfortunately, “usually unreadable”. A particular bête noire is what are known as “readings”. These, Edmundson explains, are “the application of an analytical vocabulary – Marx’s, Freud’s, Derrida’s or whoever’s – to describe and (usually) judge a work of literary art…the problem with the Marxist reading of [William] Blake is that it robs us of some splendid opportunities. We never take the time to arrive at a Blakean reading of Blake, and we never get to ask whether Blake’s vision might be true.”

Edmundson is equally forthright when he meets me for lunch during a short trip to London. Literary studies today, he argues, are often “a technique for preventing students from being influenced by the texts in front of them. It’s a mystery to me why anyone would want to do that.”

His bold and ambitious new book is partly a demonstration of what a “real education” in the humanities, inspired by the goal of “human transformation” and devoted to taking writers seriously, might look like. It developed, he tells me, out of a course he began teaching about seven years ago, “originally called Heroes and Saints, about the heroic as it is manifested in Homer and the saintly as it’s manifested in the person of Jesus”. He then became increasingly interested in Confucius and the Buddha, but also in a third ideal of deep philosophical thinking, exemplified most obviously by Plato, which attempts to discover universal truths for all time.

Building on this, Edmundson modified the course into one on “contemplation, compassion and courage as ideals. And then I worked in rebuttals against them, particularly modern writers who are very impatient with ideals. I wanted someone who was straight out an enemy of ideals and found him in Freud.”

Self and Soul, therefore, presents what Edmundson calls the “soul ideals” of Homer, Plato and Jesus. There is also a chapter on High Romanticism, represented by William Blake, who “believes passionately in the idea that by joining, sexually and spiritually, with the beloved, one can be transformed into a higher, better version of oneself and help transform the beloved as well. And from there one can do something – and perhaps more than a little – for the world at large.” Against them the book pits Freud, the “worldly pragmatist”, hostile to all such ideals as dangerous illusions, who “tries to guide his patients and readers to hard-won and often precarious inner equilibrium and to measured satisfactions”. Once the soul ideals are dismissed as dangerous or delusional, we can only fall back on the “measured satisfactions” of the self.

More surprisingly, perhaps, Self and Soul also puts Shakespeare on the side of self. It is often claimed to be impossible to deduce his values and beliefs from the plays, but Edmundson believes this is quite wrong: if Shakespeare’s values seem invisible, that is simply because they accord so well with our own.

“Shakespeare was an anti-idealist,” he explains to me, “a writer who detests chivalry, hasn’t much time for religion. Though there are some passages that can stand alone as wisdom or aspirations to wisdom, by and large people in Shakespeare ‘talk for victory’; they try to get what they want. Shakespeare depicts a world where the ideals are deflated and replaced by a kind of situational pragmatism. He is part of a crucial moment of turning towards a worldly and modern way of looking at things.”

If there is one thing that Shakespeare is particularly concerned to deflate, Edmundson’s book hopes to convince us, it is the military virtues. Macbeth is a great warrior, but – it is strongly implied – only in compensation for impotence and infertility. Coriolanus is like an overgrown child, dominated by his mother. Othello may possess the soldier’s stolid integrity but that makes him easy prey for someone like Iago, who can use words opportunistically, as weapons for achieving his aims.

So how does all this fit together? Although some of his students still believe in Romantic ideals of love, Edmundson insists that “the [other] ideals were more publicly present and available in the past than they are now. When I say to my students, ‘For a long time, people shaped their lives around compassion and bravery and the quest for truth. You can do that too’, they haven’t heard that.” What we have got instead, he explains, are a “technology of ideal-creation” and a belief that mountains of instantly accessible information can be a substitute for wisdom. Instead of true courage, we seek simulacra through sport or video games. Meanwhile, the bourgeois goals of a long, healthy life, happiness and professional success go virtually unchallenged. In that (rather odd) sense, Freud and Shakespeare have won.

Unhappy with this outcome, Edmundson tells me that he has attempted to “make the ideals available in the clearest and most provocative way, and give people the opportunity to think whether they want to embrace them or decide that Freud and Shakespeare are right and that they should live the life of the self”.

“The teacher is successful to the extent that he or she has opened up these ideal options for students, given them the opportunity to see what the ideals are at their best, and also given them the tools to ask hard questions about them. I’m thrilled if someone goes on to be a merchant banker, so long as that person has had a chance to contemplate the ideals, criticise them and say ‘no’ to them. The same applies if someone goes off to be a compassionate aid worker, provided that person has had a chance to look at the criticisms of the ideals.”

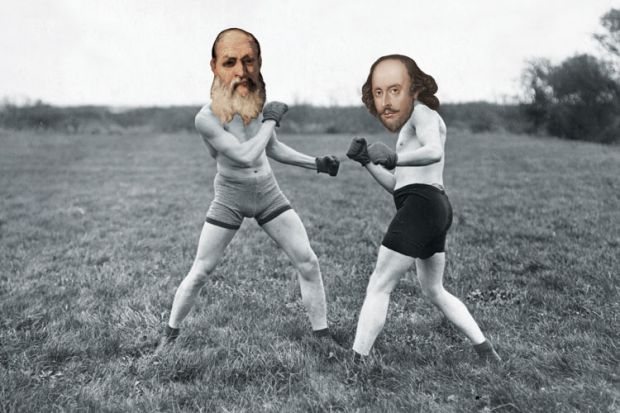

We can now take a step back. Self and Soul offers us a kind of vast debate. The speakers are all leading cultural figures, the staples of liberal arts degrees. On one side are Homer, Jesus and Plato, with Blake as a kind of substitute. In the opposite team, fighting to secure our vote about the best way to live, are Shakespeare and Freud.

The descriptions Edmundson gives of each participant are vivid and incisive, personal without being idiosyncratic, yet the overall pattern remains startling. He freely admits that he is continuing to investigate the issues and has “left a lot of questions hanging, because I wanted to make Self and Soul a book a young person could read without getting tied up in complexities”. So it seemed worth probing him about some of the gaps and surprising claims.

First of all, why does he regard his “soul states” as fundamentally similar, despite the obvious differences and indeed hostility between those who adopt courage, compassion and contemplation as their central values?

All of them can be dangerous, admits Edmundson, but “they give you a unity, a feeling of being outside of time – you are not worried about temporality when you are in them. And they all do good for other people” – or at least, in the case of warriors, for the people on their side.

Although it presents some powerful objections to the soul states, the book explicitly comes out as “seek[ing] the resurrection of Soul”. A strange aside warns that philosophers need to focus on “eternal matters” and to be careful about allowing their energies to be “absorbed into the (perhaps) real but mundane pleasures of marriage” and “the constant pressure of domestic distraction”. Asked about this, Edmundson contends that “families involve risks, they put you in the world of the self, which is the world I’m in. Just about all the instances we have of taking the ideals to the highest level involve some sort of repudiation of family.” He also feels that the goal of happiness – “a word that applies by and large to the satisfactions of middle-class families” – has been “oversold a good deal”.

Isn’t this an odd, slightly sneering note for someone to strike who has not gone off to war or founded a leper colony but freely chosen marriage, family life and professional success? Edmundson replies that there is nothing “sneering” about his “attitude to everyday middle-class life unless it is unreflected upon. If people just jump in, I don’t like it.”

And this leads to further paradoxes about Self and Soul. As one might expect in a book by a university professor, it is in favour of students being exposed to a wide range of ideas and thinking carefully about which work for them. Yet it also envisages at least some of them (how many is rather unclear) reasoning their way through to embracing the distinctly unintellectual virtues of courage or compassion.

Although less obviously dazzling and high-spirited than some of Edmundson’s earlier works, his latest book quietly sets out to challenge many educational pieties, most of the assumptions of recent literary studies – and his own chosen lifestyle. Perhaps it is not surprising that it ends up leaving open as many questions as it answers.

Mark Edmundson’s Self and Soul: A Defense of Ideals is published this month by Harvard University Press.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?