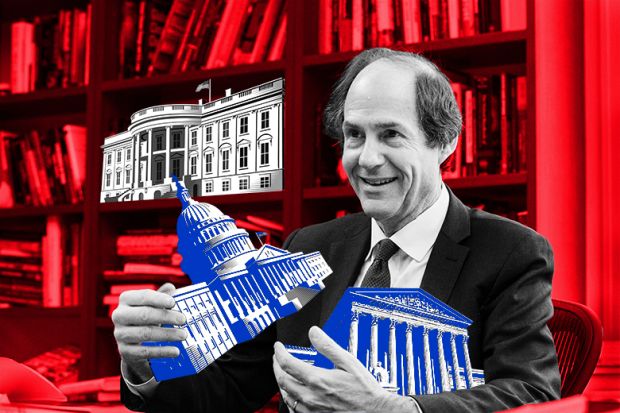

The title of Cass Sunstein’s new book, Separation of Powers: How to Preserve Liberty in Troubled Times, might lead us to expect an analysis of the turbulence unleashed by Donald Trump.

But that is not what we get. The Robert Walmsley university professor at Harvard Law School just doesn’t see his role that way. “The day I write a book saying ‘The current president is wonderful’ or ‘The current president is terrible’ is probably the day my dean comes into my office and says ‘Cass, are you OK?’” he told Times Higher Education.

As well as being the most cited legal scholar in the US, Sunstein has extensive experience in practical politics. After working as a clerk for two federal judges and at the Department of Justice, he taught at the University of Chicago for more than two decades. Then, when his friend and former colleague Barack Obama was elected president, he was appointed administrator of the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs.

In that role, Sunstein was closely involved in drawing up regulations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from power plants, to make cars more fuel-efficient, and to improve the performance of appliances such as refrigerators and microwaves. He also co-chaired a working group, he recalled, that established a precise monetary figure for “the social cost of carbon”, which was then fed into “the decision-making process in determining how stringent we should be in energy efficiency and regulations”.

During Trump’s first term as president, Sunstein returned to academic life, at Harvard, but went into government again when Joe Biden was elected – initially as a full-time senior counsellor in the Department of Homeland Security and as a part-time “special government employee”. He still has advisory roles with the World Bank, the United Nations and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, where he is currently involved in a “sludge audit”, designed to reduce the burden of bureaucracy.

A hugely prolific writer, Sunstein has “no idea” how many books he has written or co-written, but is “a little embarrassed that the number is so high”; his Harvard Faculty page lists 86, not including his latest, published across a 35-year career.

His celebrated 2008 book Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness, co-authored with Nobel laureate Richard Thaler, had a major impact on public policy in the US, UK and beyond by suggesting ways that governments can encourage citizens to act in desirable ways without forcing them to do so. (One familiar example is by making consent to organ donation the default position, requiring those who object to make the effort to opt out.)

Given Sunstein’s dizzying rate of productivity, it is perhaps unsurprising that he has published at least three books (all with MIT Press) since Trump returned to power at the beginning of 2025. All are stimulating, eloquent and informed by deep thinking and research. Yet it remains striking how much they shy away from engaging head-on with recent political developments apparently relevant both to their central concerns and to Sunstein’s areas of expertise.

Climate Justice: What Rich Nations Owe Poor Nations – and the Future, published last February, argues for a form of “climate change cosmopolitanism” and “intergenerational neutrality”. In other words, when countries are assessing the costs of their greenhouse gas emissions, the impact on “each person should be counted equally, no matter where they live, and no matter when they live”. The book includes the full text of the Paris Agreement of 2015 and claims that “The best bet, and the most optimistic, is that incremental improvements in the agreement, and multiple actions and decisions with respect to nationally determined contributions, will produce large emissions reductions.”

In concluding Climate Justice, Sunstein admits that the book has focused on “theoretical questions and on matters of right and wrong”. Hence, it is to an extent idealistic since “everyone knows that there are limits to how much wealthy nations are willing to do, both in scaling back their emissions and in providing assistance for adaptation”. But given the current administration’s views on climate change, multilateralism in general and the Paris Agreement in particular, don’t such questions feel almost irrelevant today?

Publishing the book when he did, Sunstein conceded, was “a little like writing a folk album a week after Bob Dylan went electric”. But he was unrepentant. He is a great admirer of John Stuart Mill and pointed out that both On Liberty and The Subjection of Women have become hugely influential classics even though they were published at “particularly unpropitious times” and were “running against very strong currents of opinion”. His own book “stresses a very clear need to think about the impact on the whole world when assessing the social costs of carbon. That is the principal argument – and if it is inconsistent with the zeitgeist or where public officials in my own country are, so be it.”

Similar issues arise in relation to On Liberalism: In Defence of Freedom, published last September, which is based on the claim that “more than at any time since World War II, liberalism is under pressure, even siege”. This is because right-wingers, Sunstein pointed out, often hold liberalism “responsible for the collapse of the family and traditional values”, while those on the left “think that it lacks the resources to handle the problems posed by entrenched inequalities, racism, sexism, corporate power, and environmental degradation”.

Several other writers, such as Francis Fukuyama and Yascha Mounk, have also published recent defences of liberalism. But Sunstein suggested that his is “distinctive, as an attempt to give an enthusiastic appreciative account of liberalism’s big tent”. Since he is an admirer of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal and supports a minimum wage, income redistribution, the Affordable Care Act and the Clean Air Act, he is in no sense a libertarian (or what the British sometimes call a “classical liberal”). Nonetheless, he “see[s] libertarian liberals of the Thatcher sort as part of the same general team as social democrat liberals of the FDR sort. I admire and honour libertarians because they are committed to freedom. I do not think their conception of freedom is the right one, but it’s not really the wrong one either. It has a truth to it. They are nervous about government power – hurrah for that. They love the rule of law. They believe in property rights, pluralism and freedom of speech. These are my brothers and sisters, even if we squabble.”

Such an analysis is obviously pitched at a level of abstraction far above the cut-and-thrust of daily politics. And although Sunstein reminds us that the liberal category excludes the likes of Hitler, Stalin and Putin, he has almost nothing to say about the rather more urgent question of what the current US presidency means for the liberal project. Why?

“I wouldn’t want to write a book on whether the Trump administration is a threat to liberalism,” Sunstein replied, “and I wouldn’t want to read that book. What I am aiming to do is to write a book which is not for one particular month but is of enduring interest.” When he joined forces with Daniel Kahneman and Olivier Sibony to write Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment (published in 2022), he added, they were “all clear that we didn’t want to do anything which could date the book”, so they avoided all references to current events – and even declined to use the word recently. Since they were writing as academics, they “hoped that the book might be of interest other than just after its publication. I had that book in mind when I did these other three books, even though they are more political.”

Perhaps precisely because he has first-hand experience of practical politics, Sunstein is sceptical about academics who see themselves as activists: “If a law professor or historian or physician starts thinking ‘How can I move the world in the direction I would prefer?’, they are probably not doing their jobs very well.”

When he served under President Obama, one of Sunstein’s priorities was “reducing deaths on the roads” and he had the tools to help make cars safer and discourage people from texting while driving. An excellent academic book on road safety, by contrast, “might just be read by road-safety enthusiasts and have no policy impact”. But that is fine: the role of academics is not to change the world but to “figure out what’s true”, he said.

Sunstein’s new book on the separation of political powers grew out of the realisation that the topic actually breaks down into “six things rather than one, and that each of the six things has to be explored independently”. One section, for instance, is on why the legislature may not exercise the power of the executive. Another explores why the executive cannot usurp the powers of the judiciary. And so on.

“These six things are all separate,” Sunstein went on, “and the fundamental goal of the book is to put the spotlight on each of them in turn. It’s separations of powers – in the plural. I’m a little startled that is not a familiar point. It’s an enduring issue rather than a Trump issue.”

In one passage, Sunstein does come down strongly against a 2024 ruling by the Supreme Court in Trump v United States that entails that the US now has “an immensely powerful president who is, for the first time in US history, broadly free from the operations of criminal law” – a situation he describes as “inconsistent with the highest aspirations of the system of separation of powers”. Yet elsewhere in the book Sunstein rather ties himself in knots in his desire not to be seen as partisan.

He offers a positive account of how decision-making within government can and often does involve serious-minded deliberation, noting how discussions in Obama’s White House on the social cost of carbon “involved the aggregation of a great deal of scientific, economic, and legal expertise, with agreements being forged through substantive arguments. Notably for this decision, politics – understood as electoral considerations or possible press reactions – did not play the slightest role.”

Sunstein goes on to acknowledge that his picture of government is “idealised” and ignores “an elephant in the room”, namely the second term of Donald Trump. “In 2025, at least, the sheer speed and aggressiveness of presidential action suggests that we are not speaking of an intensely deliberative process,” he writes.

Moreover, his own positive vision of government in action depends on “the assumption that most of the time, the executive branch operates as if it were not run by X” – where X is the worst possible president. “This has usually been true under both Democratic and Republican presidents,” he writes, “certainly outside of the context of the most politicised questions (and, frequently enough, in that context as well)...[But] if the president really were X, then the picture I have offered here would not be realistic.”

He concedes that “some people see Donald Trump as X”, but, in a political climate in which Trump’s second administration has repeatedly engaged in actions which subsequent lawsuits have deemed illegal, unconstitutional and beyond the limits of executive authority, many readers will no doubt be crying out for Sunstein to get off the fence and just tell us whether he agrees with that verdict.

There may be good reasons to avoid poking “the elephant in the room” and to aim instead for the literary longevity offered by abstraction. But many Americans will experience considerable cognitive dissonance as Sunstein leads them to reflect on the separation of powers without seriously engaging with the question of whether X – with all that letter’s associations with Trump cheerleader and government machinery slasher-in-chief Elon Musk – is meaningfully distinguishable from their 45th and, especially, their 47th president.

If political power in the US becomes concentrated in the hands of the executive to such an extent that liberalism is undermined, as many commentators fear, might future readers judge that Sunstein should have applied his analysis to the historical moment more explicitly?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?