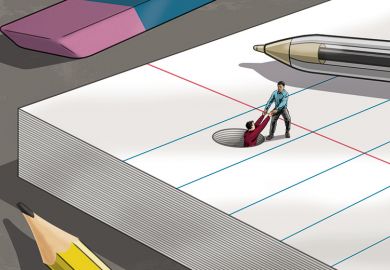

As a postgraduate or early career researcher, it is never easy to distinguish between a valuable training opportunity and an exploitative imposition. But while the jury might sometimes struggle to reach a verdict when it comes to teaching and, especially, marking, involving junior academics in the organisation of academic events is a win-win for everyone concerned.

In this ultra-competitive academic job market, the more skills and experiences to which candidates can lay claim on their CVs, the better placed they will be. Moreover, pedagogical research affirms that exercises based on participation are more effective than teacher-led learning.

The more confident junior scholars and ECRs might naturally assume the roles played by more senior academics at conferences – networking, asking questions and presenting their own research. But the majority will benefit from being given a specific role, whether it be introducing a reading, chairing a panel or keynote, summarising a conversation, live-tweeting or writing a blog post. The “low-stakes” nature of this kind of participation means that it should not be intimidating.

In addition, there is a greater chance of a community or network developing among people asked to interact in ways beyond presenting their research – for the same reasons that training days are often awaydays. Putting a postgraduate student on a panel alongside an established academic has led, in my experience, to that academic offering the student informal mentoring, or simply taking an active interest in their work. For the frequently isolated doctoral and postdoctoral scholar, this can open up opportunities for future collaborations beyond their home institutions.

It benefits more senior academics too. Digitally native junior scholars are also more likely to be comfortable with social media and blogging platforms. Using their expertise can put a local conference on a global platform, enabling online participation from afar.

I recently organised an interdisciplinary seminar series on the practice and politics of war commemoration across time, funded by a British Academy Rising Stars Engagement Award. The £13,000 enabled me to organise three one-day workshops, designed to include and train junior scholars in as many ways as possible.

I asked a master’s student to design the posters, programmes and series logo and to help me with the website. I invited postgraduates and ECRs to run the morning workshops, which meant selecting readings in advance and leading the discussion on the day. The aim was to create an intimate, thinktank-like atmosphere; the workshops’ deliberately democratic circular layout of chairs meant that participants, regardless of academic seniority, interacted on equal terms, without introductions. In the afternoon sessions, postgraduates chaired panels and introduced keynote speakers. Students even took some of the event photos.

On social media, the focus was on emerging scholars. At the workshops, the designated graduate and ECR “live-tweeters” summarised the discussions and prompted online discussion throughout the day. This helped to boost the tweeters’ profiles in the field, as well as to enable those scholars who could not attend in person to follow the conversation. I also used the series’ Twitter account to build junior scholars’ participation outside the event, inviting individuals to post topics and lead the online discussion for a week. The blog posts after the events were also written by early career scholars.

Yes, of course money matters, and financial support for this kind of collaborative intellectual activity is unusual (it allowed me to pay for all speakers’ travel, conference dinner and accommodation, to make two of the three events completely free, and to minimise the cost of the third). But giving early career scholars a prominent role in leading conference discussions does not cost much in its own right.

Admittedly, it is not always appropriate, or useful, to have junior academics running the show. More advanced scholars have more experience and expertise, and have earned their seat at their table through years of hard work. But we can all get more from workshops and conferences if we build on junior researchers’ strengths. And developing their confidence and their skill sets early can only stand them in good stead to deliver the keynotes a decade or two down the line.

Alice Kelly is a Harmsworth postdoctoral research fellow at the Rothermere American Institute, University of Oxford, and a junior research fellow at Corpus Christi College.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Events promotion

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?