In May last year, 92-year-old Olive Cooke, the UK’s longest-serving poppy seller, killed herself after being sent hundreds of letters from charities asking for money and being bombarded by phone calls requesting a donation.

The story garnered widespread coverage, with the Daily Mail denouncing “charities that prey on the kind-hearted and drove Olive to her death”.

This was not the only blow to charities’ reputation in 2015. Kids Company, which provided support to deprived children, closed last August after revelations alleging financial mismanagement.

Such negative coverage appears to be filtering through into wider public perceptions of medical research charities, according to a new survey of attitudes towards science released last week, eroding confidence in bodies that provide universities with huge amounts of money and drive the direction of new research.

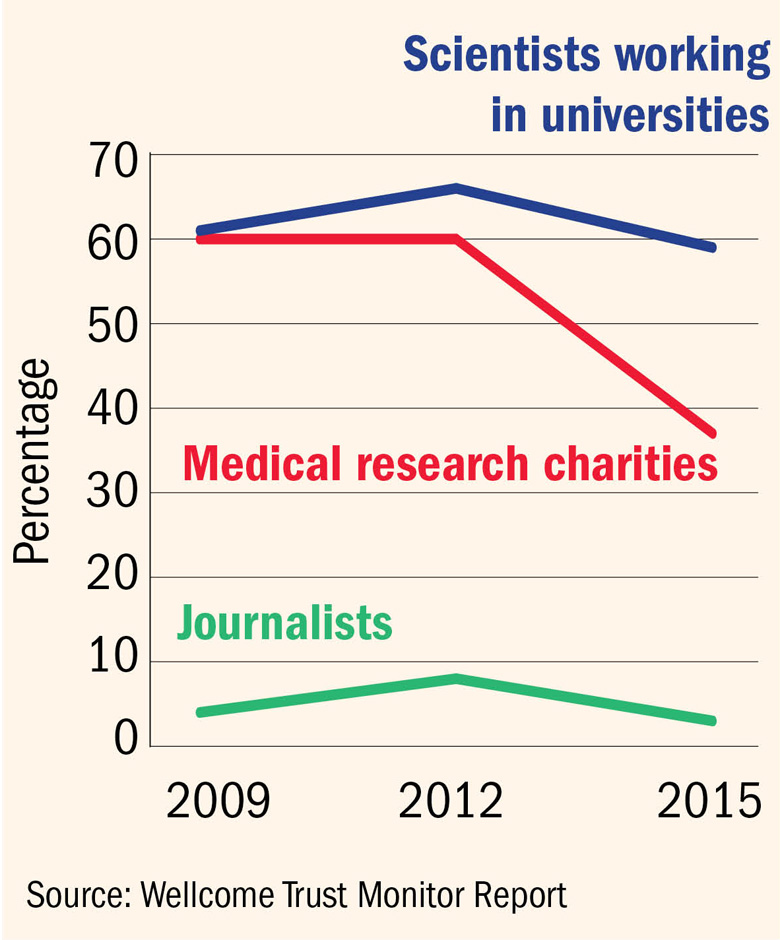

The Wellcome Trust Monitor Report, released every three years, shows that just 37 per cent of respondents said that they had “complete” or a “great deal” of trust in medical research charities to provide “accurate and reliable” information about medical research.

This is a fall from the 60 per cent recorded in 2009 and 2012, and the report cites stories like that of Olive Cooke as a potential reason for this dive in confidence. In 2015, more than one in 10 people said that they had “very little” or no trust at all in the charities, up from one in 20 in prior surveys. Older people were particularly likely to have distrust.

“Last year was a difficult year for the charity sector,” acknowledges Aisling Burnand, chief executive of the Association of Medical Research Charities. “I suspect that will have had an impact on the way the sector is viewed.”

The drop in confidence appears to have been indiscriminate: the scandals of 2015 were about fundraising and management, but they nonetheless appeared to hit trust in the quality of information charities give out.

Patrick Sturgis, who led the survey’s working group, suggested that a campaign – which prominently targeted the Wellcome Trust – urging charities to end their investment in fossil fuels could also have had an impact.

The stakes for universities and academics are high: medical research charities fund more research than even the taxpayer-backed Medical Research Council. In 2013-14, members of the AMRC contributed almost £1.3 billion overall to such research.

Will trust in medical charities return to previous levels, or continue to decline? Ms Burnand pointed out that “income is still coming in” to the charity sector despite negative headlines, and that in the wake of events last year, “many organisations have been looking seriously at their standards of fundraising”.

Last month, Cancer Research UK announced that from April, donors would not receive future requests for money unless they specifically opted to do so.

Professor Sturgis, who is a professor of research methodology at the University of Southampton, pointed out that the dip in trust might also be explained by a methodological change. Previously, respondents had been asked about trust in medical charities immediately after being quizzed on their views about government departments and ministers. But in 2015, the medical charities part came immediately after a question about doctors and nurses, which are generally far more trusted.

This framing effect could have made charities seem more untrustworthy by comparison. “My intuition is that this [decline in trust] will revert back [to normal]” in the next survey, he said.

Doctors, nurses and other medical practitioners are still the most trusted source of information about medical research, with 64 per cent placing “complete” or a “great deal” of trust in them, although this is down from 72 per cent in 2009.

Scientists in universities come second, with 59 per cent. This is down seven percentage points on 2012, although similar to levels seen in 2009.

Just 32 per cent of people trust scientists working in pharmaceutical companies, and 29 per cent trust scientists “in private industry”. This distrust was largely because respondents felt that they would “exaggerate” information, or “try to present themselves in the most positive light”.

Curiously, the more educated people are, the more likely they are to trust university scientists – but trust private sector scientists less.

Trust: who do we believe?

Percentage of respondents saying that they have “complete” or a “great deal” of trust in a group to provide “accurate and reliable” information about medical research

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?