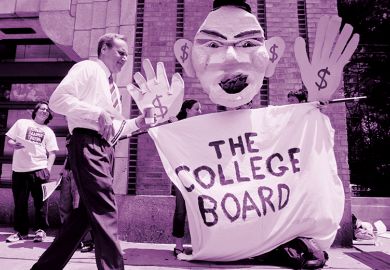

The US’ main admissions testing service has retreated from its plan to give students taking its exams a single score expressing their socioeconomic status, hoping to quell criticism that it inadequately tackled known biases in standardised testing.

The College Board said that it would instead offer institutions a menu of demographic and community data on applicants who take its SAT assessment of college readiness.

The initial plan, announced in the spring, would have taken much of the same data and combined it into a single measure of “overall disadvantage” for each student, on a scale of 1 to 100.

The new product, called Landscape, will present such raw data alongside two 1-to-100 scales – one summarising the student’s high school population and one summarising the student’s neighbourhood – based on six of the data points, including the area’s rates of education, crime and family income.

“We listened to thoughtful criticism and made Landscape better and more transparent,” said David Coleman, the College Board's chief executive. “Landscape provides admissions officers more consistent background information so they can fairly consider every student, no matter where they live and learn.” In an interview with the Associated Press, he said the initial “idea of a single score was wrong”.

The main objection to the first version, a College Board spokesman said, centred on concerns that a single 1-to-100 rating covering multiple demographic data points seemed to be a score of the actual student, alongside his or her SAT results in mathematics, reading and writing.

The new version, said the spokesman, “allows people to see that it's not about them – it’s about the community that they're in, it's about the school that they’re in, and it’s not their personalised information”.

Many complaints about the initial College Board plan, however, were broader critiques of the real-world complexity of grading students – on both their academic achievements and the various obstacles in their lives – through simple numerical indicators.

US universities created the College Board in 1899 for the purpose of establishing an admissions test, but have begun abandoning the SAT in recent years, owing to concerns that it favours wealthier and whiter students, and often fails to predict college success.

It has been a long-standing concern. Carl Brigham, a professor of psychology at Princeton University who created the SAT in the 1920s, held racist views about innate intelligence but later acknowledged that standardised test scores reflected many outside factors including family background and fluency in English.

The College Board’s new demographic tool, while making no direct measure of race, was intended to help colleges address such concerns. Yale University, among more than 50 institutions that had been testing the initial version, reported that the data helped it register significant gains in low-income and first-generation freshmen.

It was less clear whether the tool will provide colleges with information to make their campuses more racially diverse, without the political and legal obstacles associated with race-based preferences.

Either way, the major grouping of public US universities endorsed the shift from a single 1-to-100 measure as a way to give colleges greater information about their applicants in a manner more transparent to all.

The College Board’s change was valuable, said a spokesman for the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, because it “gives students and families certainty about what information admissions officials would be able to view through the tool”.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?