Let’s take a scenario many of us have faced: you’re on the phone in your office when someone enters with a large sheaf of papers, red in the face. While you mumble into the phone “Something’s come up…call you back?” your visitor heavily takes a seat and stares at you, as if summoning the power of Medusa to turn you to stone. Thus begins another “challenging conversation” to sweeten your day.

Leading Roles is a team of experienced actors and senior higher education staff from Teesside University who have been using applied theatre techniques for the past 10 years to help people in higher education and business manage potential conflict more effectively.

Our aim is to encourage senior leaders to communicate and engage more comfortably and confidently with their colleagues and clients, to achieve the best version of a challenging conversation.

We have worked with clients including the UK’s Leadership Foundation for Higher Education (now part of Advance HE) to deliver programmes for staff across the sector, as well as with health authorities and private companies.

Our longest-running piece, Moving History, is a half-day scenario about change in a university history department. It is highly interactive but without the pitfalls of role play, utilising instead a series of theatre techniques and processes to explore the situation.

If you use the phrase “role play” to most people, it can conjure up some bad memories or experiences. In our work, we employ professional actors to bring the work to life and make it as compelling as possible, and we commission scripts from professional writers who have experience of the higher education sector – thus the situations feel immediately authentic.

Moving History begins with that uninvited entry to an office and ends with a host of reflections on how to prevent confrontation, solutions generated by our participants as they guide the scene and the actors towards the goal of engaged and considered resolution.

We aim to help participants examine the situation from different perspectives, as if they are one among several actors in a wider piece.

We ask them to adopt the “director’s” position and consider what this scenario might look like to a wider audience. What might we read from body language and tone of voice? How might we adapt behaviour to ensure that the specific messages we want to convey are more consistent?

We create opportunities for participants to share their thoughts around specific knotty dilemmas they have seen played out in the drama, asking them to justify their positions, enabling them to hear the thoughts of their peers and, perhaps most importantly, to change their minds.

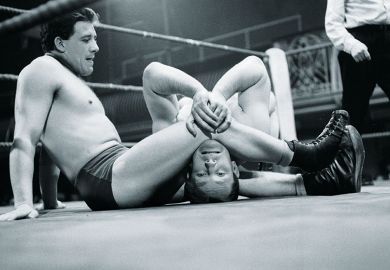

Drawing on Augusto Boal’s Forum Theatre methodologies, we stop and start the action – as we would in rehearsal – sharpening technique, changing the script, testing how a particular apology might “land”, challenging assumptions and habitual thinking that might not serve as effectively as taking a different approach.

We ask participants to “coach” a character, taking ownership of their actor and working with them to achieve a desired outcome. Sometimes we stop the action mid-scene and ask the participants in the audience to rate the characters out of 10 in terms of their effectiveness in a role, asking them to justify their scores and identify what changes might improve the outcomes.

We place the emphasis on planning how to behave, as well as on what to say, and on rehearsing the ability to summon the best version of yourself to suit the circumstance you find yourself in.

We introduce techniques to develop the skills of keeping calm and managing your emotions. Slow, silent counting and breathing deeply can sometimes help as you listen. How can you also bring both honesty and integrity to the conversation? By being very clear about what you can and cannot promise, and about what power and responsibility you have to meet requests.

The ability to listen empathetically to another person is a difficult skill to master, but when done well it has the potential to help resolve challenging situations. Showing carefully, through the drama, what “good listening” looks like, how moving and satisfying it can feel to be listened to, without interruption and with respect, can often be revelatory to many of our participants.

Sudden fires will always start, but if you can master the “heat in your own moment”, much of the pain is taken out of a potentially difficult situation, along with much of the stress that arrives in the anticipation of such situations.

Sharon Paterson is associate director of culture and engagement at Teesside University. This article was co-written with Paul Hessey and Mike Rogers, part of the Leading Roles team.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: To perform well, rehearse ‘challenging conversations’

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?