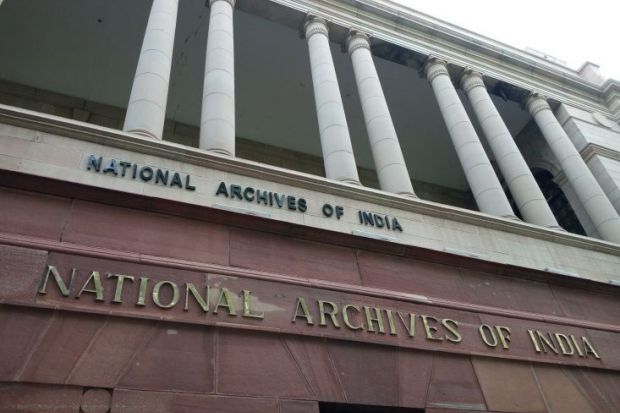

Asian studies scholars have expressed alarm over the planned demolition of the National Archives of India (NAI) Annexe, which houses hundreds of thousands of historic documents.

That building, the National Museum and the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts will all be disrupted as part of the government’s Central Vista project to redevelop central Delhi.

A petition signed by thousands of global academics calls for transparency in how the annexe’s materials will be handled.

“The loss or damage of a single object or archival record would be an irrevocable loss,” the petition said. “These historical documents, maps and objects are not only central to the modern Indian nation but germane to broader academic research on the South Asian subcontinent and the reconstruction of global histories of migration, political, economic and cultural exchange.”

The housing and urban affairs minister reassured critics in late May that the NAI would not be destroyed as a heritage building; but that protection does not extend to the annexe.

Experts lacked confidence that government officials had the linguistic and archival expertise required to ensure that the documents remained organised and safe while in temporary storage.

Swapna Kona Nayudu, an associate at the Harvard University Asia Centre and at the National University of Singapore’s Asia Research Institute, told Times Higher Education that anxiety stemmed from “a systemic issue with the handling of archival materials in India, especially in government-run organisations”.

The academic community had “significant concerns” about the documents’ “physical safety, which was already often compromised, and may not survive this move”, she said. “The significance of these materials could not be overstated.”

She wrote recently that “what historians specifically are feeling is not only shock, but also a sense of bereavement as the discipline depends so heavily on these materials and on access to them”.

Sana Aziz, an assistant professor of history at Aligarh Muslim University, recently detailed the materials in the Annexe, some of which date back to the mid-18th century. These include “six lakh [600,000] documents pertaining to the pensions of freedom fighters, ten lakh [1 million] claim files of post-Partition immigrants from Pakistan, a huge bulk of military records and those of the Archaeological Survey of India,” she wrote.

Dr Aziz told THE that one underlying problem was “the gradual diminishing capacity of scholars today to engage with the classical languages like Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit”.

There are also fears that the move could affect critical study of India’s history. “The transfer of records would entail a general deterioration in academic freedom, with no or limited access to the archival records,” Dr Aziz said.

There may also be a political dimension to the move.

“The ruling dispensation has had a revisionist approach to history, with an emphasis on Hindutva nationalism, so archival materials that reflect India’s pluralist and secular past are under grave threat,” Dr Kona Nayudu said.

In fact, many of the materials only became widely available to scholars in the early 2000s and still required “jumping through hoops” to access.

If they are hidden away in storage, they may “may cease to exist or, at the very least, become untraceable”, she said.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?