Emerging higher education systems in Southeast Asia may need to be wary of focusing too much on creating a handful of “world-class” universities to boost international research collaboration, according to a British Council report.

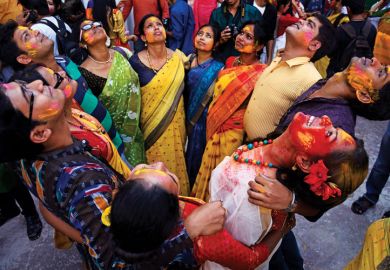

The study, which looks at policy among countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), is being released to coincide with the British Council’s annual Going Global conference, held this year in Kuala Lumpur, the Malaysian capital, from 2 to 4 May.

According to the report, The Shape of Global Higher Education Policy: Understanding the Asean Region, it is “evident” that there is a “commitment throughout the region to building research collaboration with those outside and within Asean”.

Although some Asean nations such as Singapore are better positioned to exploit cross-border working, the study says that all the countries appear to believe in the need to have at least one world-class university to foster international collaboration.

However, the implications of this need to be “considered carefully” as this “may inevitably come at the expense of the development of international research collaborations across the whole of the higher education system”, it adds.

The observations on the strength of research collaboration in Southeast Asia are backed up by a new analysis of data from Times Higher Education’s World University Rankings 2018 carried out for the conference.

It shows that even after attempting to allow for the extremely high-performing Singaporean universities in the ranking by using median instead of mean scores, Asean institutions as a bloc tend to outperform other countries in Asia on international research collaboration.

The 26 Asean ranked universities, which hail from countries as diverse as Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia, achieve a median score for international co-authorship of 50, way ahead of China (median score 11), India (8) and even nations with a similar number of ranked institutions such as South Korea (21).

Even looking at some individual countries in the Asean network compared with other Asian nations shows that research collaboration is one of their comparative strengths, when considering only ranked universities.

But whether there is a risk that concentrating too much on “world-class” universities could harm a developing higher education system overall is a key question that has been explored by international higher education scholars.

Simon Marginson, professor of higher education at the UCL Institute of Education and director of the Centre for Global Higher Education, said that focusing government funding on such institutions can be “suboptimal” in the long term.

“It is possible to balance development effectively so that the whole system improves,” he said, adding that governments should “pay special attention to ensuring a strong ‘middle sector’ which conducts research and is just below the top bracket”.

“Middle-income developing countries are often anxious to build a couple of global research universities in five to 10 years, but it might be better in a country like, say, Indonesia…or Vietnam to build a stronger layer of 10 to 20 institutions and spend 15 to 20 years building the world-class universities.”

Caroline Wagner, Milton and Roslyn Wolf chair of international affairs at Ohio State University, said that “while it is important to have appropriate scale built into institutions to conduct strong research, it is also necessary to have regional and local nodes to diffuse knowledge”.

“World-class universities tend to focus on connecting at the international level,” she added. “This enhances competitiveness, which can also bolster quality. But unless there is capacity to link knowledge to local users, then knowledge just stays in the ‘cloud’ and does not enrich national well-being.

“Linking to top research around the world needs to be combined with a plan to sink knowledge locally,” she explained.

“If the world-class departments work only with colleagues in other countries, the investment is a net loss for the nation,” Professor Wagner continued. “Capacity needs to be nurtured in regional and local institutions so they can absorb, use, teach and train the science and technology workforce.”

She pointed to data on Malaysia that suggested that research was “already fairly well integrated into the international community” but said that this did raise the question of “what are they doing to diffuse this knowledge to local users?”

The local impact of universities that are increasingly interconnected globally will be the key theme of this year’s Going Global.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?