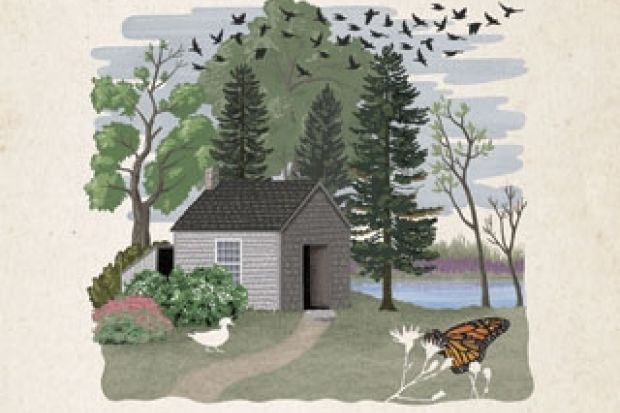

Henry David Thoreau never meant to be a conservation hero. He just went walking in the woods. He lived in a hut, watching nature carefully, alone but not lonely, writing a daily journal, growing closer over time to the wildness of mid-Massachusetts. Walden: or, Life in the Woods was published 160 years ago this year, and since then has become an iconic text for its ability to shine a brilliant light on human interactions with the sublime in nature. “I wished to live deliberately,” Thoreau wrote. “I wanted to live deep.” Less than a decade later, he died of tuberculosis, aged only 45.

Phenology is the study of recurring seasonal events marked by plants and animals, their hibernations and migrations, leaf falls and the flowering of blossom. These are shaped by environmental signals as well as genetics: temperature, day length, light intensity, moisture. Carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere were at pre-industrial levels of about 280 parts per million at the time that Thoreau, the son of a Concord pencil-maker and his wife, was born. In the ensuing years, we have experienced a seemingly unstoppable pace of economic and technological advance, and carbon dioxide levels recently exceeded 400 ppm. With the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change releasing the first part of its Fifth Assessment Report late in 2013, uncertainty over both the causes and consequences of these changes is at an all-time low. High material consumption in industrialised cultures has driven up greenhouse gas levels. These have captured energy in the atmosphere, and temperatures have increased at all latitudes and in all environments. Both climate and weather are changing and becoming more extreme. It is likely to get worse.

But few people today would wish to live like Thoreau; “to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life”. Active opposition to climate change is remarkably persistent, even though much of what the deniers profess is unscientific, unproven and worthy of profound distrust. But as England recovers from major floods, California bakes in its worst-ever drought and Arctic ice thins and retreats, denialism is no more than a body of work we should just plain dismiss. Thoreau recorded the first flowering of highbush blueberry as 11 May 1853. Today, observes Boston University biologist Richard Primack, he would have missed them. Now these white tubular flowers typically appear three weeks earlier, and in 2012 were a full six weeks earlier. “Climate change is coming to Walden Pond,” Primack concludes.

In Walden Warming, Primack and his students observe today’s Walden in an attempt to document these changes. They dig into libraries and records, compare lists of birds and plants and the population records of frogs and mosquitoes and walk the woods around the pond. Of course, much else has changed since Thoreau’s era, with the advent of suburban sprawl, modern farming, water management, abundant deer and more traffic. But a decade of research by Primack and his students has revealed something sour and clear. Some native plants have declined or disappeared, including mints, many orchids and seven species of bladderwort; at the same time, invasive species have become abundant. Ice is no longer common on the winter pond. Each chapter of this book documents alarming change: the flowering of the pink lady’s slipper orchid has begun three weeks earlier; wild apple blossoms have advanced by two to four weeks; wood sorrel by six weeks. If plant communities are changing, then so are their associated insects and other animals. These systems have been unroofed.

I do have minor quibbles with this troubling account: at times, there is too much focus on method and “what we did next”, and too little on clear summaries of impact. An odd chapter on running marathons struggles to make links with Thoreau’s own active life; an opening segment elides research in Borneo with Boston; an elaboration on back-garden flooding during a severe spring storm sows seeds of doubt about whether it is weather or climate we should be worried about; and throughout, there is persistent use of the unhelpful term “global warming”.

Living a little more simply, valuing non-material consumption, visiting, giving, walking, watching: all these might help. “It is time to take action,” Primack urges. This is not a book that will tell us how. It does, however, show compellingly how a place and its ecosystems can alter dramatically in the face of climate change. It is thus suggestive of future directions, unless common languages can be found that will unite those who recognise this kind of evidence with a nod, and those who continue to believe it is all a conspiracy.

Despite medical advances, tuberculosis still kills 1.4 million people worldwide each year. Climate change will make it more common, and possibly untreatable.

Walden Warming: Climate Change Comes to Thoreau’s Woods

By Richard B. Primack

University of Chicago Press, 264pp, £18.00

ISBN 9780226682686 and 062211 (e-book)

Published 24 March 2014

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?