Disease as just bodily destruction and death? Think again, pathology can be beautiful. The Wellcome Image Awards bring stunning examples of diseased and disordered body parts into the public domain. For instant gratification, look at #PathArt. Many of this feed’s images use innovative techniques in the life sciences to magnify, colour and enhance the natural samples. Such manipulation adds to the aesthetic effect and draws out the links with contemporary art. To the scientifically uninitiated, the patterns, shapes and hues dominate the organic substance. A frisson sometimes follows the discovery that this was once living material.

Behind our current interest in making such cellular and bodily transformations attractive and accessible lies a much longer history of pathological illustration, a territory that is ably introduced by Domenico Bertoloni Meli.

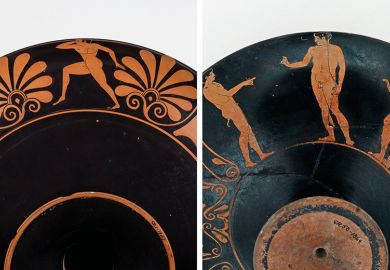

It is well known that understanding representations of the normal human body since the Renaissance draws on a synergy of art and anatomy. There has been much less work on the depiction of the body (and particularly its murky interior) in sickness. The potential richness, and poignancy, of seeing ourselves in this way underscores Meli’s venture. In a relatively open field he chooses (for good reasons) to begin in the early modern period, with the rise of pathological illustration, and then journey on with his readers to the first decades of the 19th century.

For Meli, this is a period of fascinating changes in the understanding and depiction of diseases in Europe. Practitioners concerned with the display of pathological anatomy crossed the familiar professional lines between surgeons and physicians. Early on, they often created museums of prepared diseased body parts that formed the basis for the illustrations. Learning to see and differentiate pathologies, and then through their visual presentation to think differently about the disease process, were intimately connected. There was an important shift in emphasis. The extraordinary or freakish cases that would still be considered unusual today gave way to seeking out the normally abnormal. With this emerged a deeper appreciation that the changes seen were predictable in particular illnesses.

The story is built around interlocking groups of men (female involvement was exceptional). There were the medics who carved out the tissues for display. Then artists created the initial images and adapted the originals for reproduction or passed them on to expert engravers or lithographers to make illustrations for print. Sons followed fathers in both professions. Some artists were also engravers, some anatomists used artistically talented medical students. The patient was usually dead (although those with skin diseases were an important exception). The tissue for study had been subject to postmortem changes and the rigours of anatomical preparation. Then came the usual problems of using two dimensions to represent complex structures with subtle variations of texture, tone and colour. Renowned natural history painters and botanical artists transferred their skills to pathology, if they could cope with the subject matter. The book is dedicated appropriately to those whose bodies and suffering made pathological illustrations possible – and from whom we all benefit.

Helen Bynum is an honorary research associate in the department of anthropology at UCL. She is currently co-writing Disease: A Very Short Introduction for Oxford University Press.

Visualizing Disease: The Art and History of Pathological Illustrations

By Domenico Bertoloni Meli

University of Chicago Press 288pp, £41.50

ISBN 9780226110295

Published 19 February 2018

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Graphic insight into ill health

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?