When we consider examples of other species as entire creatures, people don’t usually struggle to say what they are like. They are whole beings, open to inspection. We note similarities and differences, but each is best dealt with in its own terms.

Inquire within, though, with scalpel, microscope or some fancy modern molecular tweezers, and every specimen is packed with stuff only to be understood in terms of something else. And cell biology, whether of cells in the mass, single cells or the deeper complexities of organelles, intracellular compartments and molecules, is awash with metaphors that help us do that.

Metaphors are not just handy for popularisers, argues Andrew Reynolds, they have been crucial to scientific practice. He charts the currents of metaphor that have shaped ideas in cell biology for 350 years, since Robert Hooke first used the word “cell” to denote structures he discerned in cork. The word “cell” itself – Hooke was probably thinking of beehives, not imprisonment – is now a dead metaphor. But metaphorical visions of cells’ workings are very much alive.

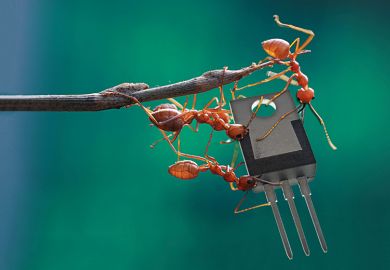

Cells are factories, equipped with innumerable molecular machines. And they are members of a community, living individuals that have their own intricate social organisation. That organisation relies on cell-cell communication, on molecular messengers, switches and relays, circuits and signalling networks.

Reynolds explains how these metaphors play out, and why they have been essential to research programmes. They are guides to hypothesising, aids to designing experiments and indispensable elements in explanation. And he argues that, as engineering metaphors underpin the new field of synthetic biology, they inform a mindset that looks for ways to redesign living things.

All this affects our view of how science works. Here Reynolds digs deeper by considering the metaphors typically used to describe how scientists use metaphors. They are ways to view a subject from a new perspective, or through a different lens (hence his title). Or they are cognitive tools. Although both approaches can be useful, Reynolds emphasises that the first is inadequate by itself: metaphors built into explanations, or inspiring projects to intervene, are more than just adjustments to an angle of vision.

That leads to a final question: what can metaphors contribute to the search for truth about reality? Reynolds’ realism is of a qualified, pragmatic kind inspired by Charles Pierce. Scientific theories cannot mirror reality, he argues. They need to be empirically adequate, instrumentally useful. Metaphor can help to achieve both. And he takes history as warrant for a strong pluralism. Sometimes one metaphor will be of most use, sometimes another. They do not necessarily have to be consistent, and it is fine to keep two or more in play at once – as long as the research moves forward.

It’s a big conclusion to offer for science in general from the study of a single discipline, although this brief, admirably lucid, volume seems to show that it works well for cell biology. And that certainly backs up Reynolds’ wider message to historians, philosophers and sociologists of science: “Metaphor is a real element of scientific activity, and it is time that it be recognised as such and treated with the seriousness it deserves.” His example should be an encouragement to explore other fields in the same way.

Jon Turney is a science writer and visiting lecturer in science publishing at Bath Spa University. His latest book, Cracking Neuroscience, has just been published.

The Third Lens: Metaphor and the Creation of Modern Cell Biology

By Andrew S. Reynolds

University of Chicago Press

272pp, £67.50 and £22.50

ISBN 9780226563121 and 3268

Published 7 August 2018

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?