“Maybe,” Michel Foucault mischievously suggests, “you’ll be somewhat shocked and disappointed by the paucity of what I have to say.” I blush, struck by the uncanniness of being second-guessed by the long-dead. He continues: “But I would like very much that you pay attention to this paucity, because I want you to become aware of this cavity of language that has continued to dig into literature since its existence.” I frown, unconvinced by his wily attempt to spin limitation as profundity.

Likewise Foucault’s editors, in their concise introduction to this collection of previously unpublished material, spin hard and fast in a bid to conceal its paucity, as they seek to sharpen the edges of the text and align Foucault’s most persistent concerns with the literary and the contemporary. They ask: if literature creates “dis-order” or stimulates transgression – of linguistic structures, institutional norms and identities – how can we translate this interruptive energy into other registers, into political projects and reconfigurations? If, as Foucault concludes, the “outside” is a myth, how can literature enable us to imagine and enact “a different speech or way of life” from within the airless confines of existing practices, images and power relations?

I am hooked by these questions, excited by the possibility that Foucault might provide responses sufficiently inventive to reinvigorate philosophy’s waning interest in literature.

The problem is that he feels like the weakest interlocutor in a conversation that took place 40 or so years ago. His work here isn’t bad or wrong, but why bother exhuming and editing aged material for posthumous publication unless it promises a killer intervention, reigniting the old conversation or sparking a new one? The most persuasive justification for the publication of these texts – transcripts of interviews, lectures and talks – is that they deliver a new site for Foucault’s archaeo-genealogical explorations. Yet this encounter delivers familiar insights: literature reconfigures social and cultural signs; is self-contradictory, consisting of transgression and repetition; is akin to madness, as both pilfer the same linguistic larder; is untimely, speaking “from beyond the grave”. In short, it contains little unsaid by Bataille, Barthes, Blanchot or Derrida, who are altogether more incisive readers of literature. Foucault’s unique promise – the translation of these insights into a political vernacular fit for the 21st century – is largely unfulfilled here.

More disappointing still is the reading experience, devoid of the flair and flight that characterises Foucault at his most magnetic. The central texts, “What is Literature?” and “What is the Language of Literature?” are dense and abstracted, immobile and inoperative. Literature itself barely makes a showing. The transcribed radio lectures “Language and Madness” are more textually engaged yet no more supple; here literature appears as great monolithic chunks of Shakespeare and Cervantes, lodged, immobile, in the text. At a time when we are saturated with philosophical readings of the Marquis de Sade, Foucault’s reduction of Sadeian libertinism to prosaic academese – a numerical list of the “functions of…Sadean discourses” – proves soporific rather than seductive. And yet there is something – an exploration of the ties between discourse and desire, the setting of Sade on a philosophical stage, and the recuperation of theoretical discourse as liberating, not limiting – that lives and moves. Here, briefly, philosophy, politics and literature are thought together.

Foucault has never been hotter, his influence never wider-reaching, his tools and methodologies never more exercised. We have much still to learn from him about ethics, freedom and power; about the “human” in an era of post-humanism; and, as philosophers begin to acknowledge his philosophical contribution, about both the history and future of critique. Less to learn, perhaps, about Shakespeare and Cervantes.

Danielle Sands is lecturer in comparative literature, Royal Holloway, University of London.

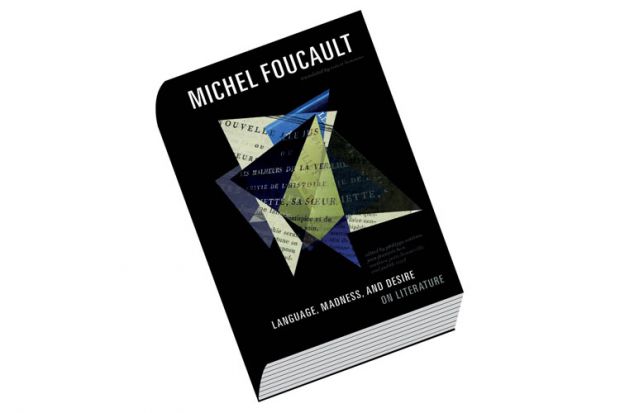

Language, Madness, and Desire: On Literature

By Michel Foucault

Edited by Philippe Artières, Jean-François Bert, Mathieu Potte-Bonneville and Judith Revel, translated by Robert Bononno

University of Minnesota Press, 176pp, £22.50

ISBN 9780816693238

Published 1 August 2015

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?