In the era of Trumped-up travel bans and a dis-Maying upsurge in xenophobia, Richard Ivan Jobs’ erudite and lively Backpack Ambassadors offers a bittersweet reminder of hopes for an integrated Europe that may now feel as remote to readers as youth itself. Describing young backpackers’ trajectories across national boundaries, Jobs shows how “youth travel acted as a circuitry interconnecting more and more of Europe…perforat[ing] nation-state territorial containers”. This bottom-up cross-border mobility helped to foster European social and cultural integration between the end of the Second World War and the end of the Cold War, “promoting fraternity” that helped to diminish, if not fully demolish, institutional barriers to European unification.

In addition to conventional scholarly sources including Pierre-Yves Saunier’s Transnational History (2013), Jobs draws on fictional narratives such as David Lodge’s autobiographical Out of the Shelter (1970), E. P. Thompson’s account of international youth brigades in The Railway: An Adventure in Construction (1948), and a wide variety of first-hand anecdotal evidence – including his own – that includes unpublished journals, memoirs and letters located in private repositories scattered throughout Europe. These sources not only lend immediacy to Jobs’ claims, but also provide important female perspectives. Unearthing these materials, he observes, represented a significant challenge, as “the young don’t leave much of an archival trail”.

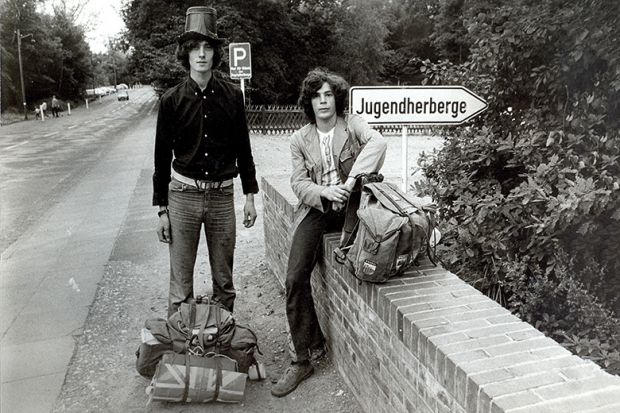

According to Jobs, non-state actors were more responsible for bringing about the transnational integration of Western Europe than the formal institutions of governments or other political entities. Youth hostels, designed initially as a project for German national integration in the 1920s but shortly thereafter part of Nazi politicisation, became by 1945 principal agents for internationalism through the newly created International Youth Hostel Federation. What began after the First World War as a quest by young Germans to understand themselves transformed into the IYHF platform, which aimed to “bring together the peoples of the world”. (Notwithstanding, even as late as 1962 I found somewhat disconcerting a Westphalian youth hostel’s loudspeaker wake-up command: “Achtung! Achtung! Raus! Raus!”)

“Cultural reconstruction” often faced greater obstacles, both practical and cultural, outside Germany. The Catholic Church, for example, worried that increased numbers of young female tourists staying overnight with young men in campgrounds and youth hostels presented a threat to conventional sexual mores. When hitch-hiking, or “autostop”, became commonplace, government campaigns in a number of countries attempted to discourage the practice through legal prohibitions. And it took concerted efforts by organisations such as the European Youth Campaign to achieve reduced rail fares for younger travellers.

Jobs also documents the powerful combination of political, economic and social forces that favoured tourism by the young. Post-war prosperity contributed significantly to increased mobility, as did proliferating educational opportunities – especially for American university students taking their famed junior year abroad. Interactions among young people were even encouraged by the CIA, keen to counter Soviet influence during the Cold War. More important still was idealism, characteristically associated with the younger generation and typified by the “Mud Angels” who came to Florence from all over Europe in November 1966 to fight to save the city’s cultural heritage when the Arno broke its banks.

The massive scale of recreational travel by the young of the era, in contrast with that of prior generations, is supported not only by Jobs’ abundant statistical evidence but my own experience. In the crowd awaiting dismantlement of Checkpoint Charlie on 25 June 1990, I met a 60-year-old East Berliner preparing to travel outside East Germany for the very first time. He had received a plane ticket to London as thanks for his interview about returning a book to a library in West Berlin on 9 November 1989 – a book he had checked out on 2 August 1961. In a lovely bit of serendipity, the book was Jack Kerouac’s On the Road.

By the 1950s, informal contacts in youth hostels and vacation camps had become recognised opportunities for state agencies to sponsor organised gatherings, such as the Youth Rally at Lorelei Rock overlooking the Rhine in 1951. Officially designated The European Youth Meeting, this bilateral event aimed to promote post-war reconciliation between Germany and France by formalising personal interactions among young people, thus advancing rapprochement between their two countries. Specifically, the Lorelei event was designed to counter the Soviet-backed World Youth Festival held earlier that year in East Berlin, with both sides seeing young people as crucial foils in the Cold War.

While France and Germany continued to foster informal relationships through increased numbers of youth hostels, seeing them as useful in promoting fraternity among young people, formal exchanges focused on language acquisition and the arts were also important to cultural integration between the two countries, as Jobs details. By the early 1960s these enterprises were institutionalised through the Franco-German Youth Office, which underwrote and expanded cultural exchange initiatives such as vocational internships, apprenticeships, and artistic and linguistic programmes. These organised, state-sponsored cultural activities gradually became less about reconciliation and more about the foundation of an integrated Europe.

But it was the advent of student activism in 1968 that would bring full-fledged repudiation of the nation state. Epitomising a newly radical internationalism was the challenge to national boundaries embodied by Daniel (“Dany the Red”) Cohn-Bendit, who proclaimed his statelessness as a German Jew born, raised and educated in France, but holding a German passport. Prevented by immigration authorities from re-entering the UK and France, he became the focus of widespread youth protests that challenged the very concept of nationality. Youth hostels, once just waystations for weary backpackers seeking a bed, had by then become sites for young people to hone their political activism. Even the benign Franco-German Youth Office faced demands to become the European Office of Youth; so that by the end of the 1960s, without an actual organised conspiracy, widespread travel by European youth had produced, says Jobs, “a sense of solidarity, interactivity, common purpose and common identity” that favoured dismantling international borders.

As well as the direct political consequences of youth travel, Jobs examines the broader implications for “communities of practice” (ad hoc social interactions) stemming from young backpackers’ widespread drug use and transgressive sexual practices, and counterculture phenomena such as New Age vagabonds. Much as travel has always implied a quest of self-discovery and therefore has been mainly a self-directed rite of passage, even informal relationships among people joined by proximity in youth hostels and by shared involvement in sex, drugs and rock’n’roll inevitably promoted collectivism.

Mass media – and rock music in particular – became major catalysts for traversing the otherwise circumscribed peripheries separating youth on opposite sides of the Iron Curtain. For instance, the 1972 International Youth Festival held in East Berlin, although sponsored by East German officials, brought young East and West Berliners together in ways the authorities had not intended, thanks to the subversive appeal of shared rock music. Music festivals throughout Europe became yet another mechanism for advancing the political internationalism that culminated in the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, which formally established the European Union and enshrined in Article 45 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights the guarantee of freedom of movement to all EU citizens.

Assiduous archival research, together with compelling narratives of young people’s personal travel experience, including Jobs’ own, make Backpack Ambassadors a potent antidote to demoralising accounts of Geert Wilders and Marine Le Pen. Nevertheless, although Jobs himself rejects despair at Theresa May’s decision to invoke Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, reading this book feels a little like coming across an archival photo of craftsmen proudly displaying their handiwork: the statues of “Honour and Glory Crowning Time” that adorned a clock panel on the grand staircase of the RMS Titanic.

Richard J. Larschan is English professor emeritus, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth.

Backpack Ambassadors: How Youth Travel Integrated Europe

By Richard Ivan Jobs

University of Chicago Press, 352pp, £79.00 and £26.50

ISBN 9780226438979, 462035 and 439020 (e-book)

Published 16 June 2017

The author

Richard Ivan Jobs, professor of modern European history at Pacific University in Oregon, was born and raised in the small town of Murray in western Kentucky. “I had a lot of independence,” he says, “and spent a lot of time playing with friends outside in woods and creeks”.

Growing up in a college town, he says, “many of my schoolmates and close friends were the children of academic faculty. This had a tremendous impact on me and how I approached and understood the world by teaching me to value intellect and recognise that, as remote as Murray might have been, it was still interconnected with places far beyond the realm of my experience.”

Jobs was a good student, and “with a university in my hometown, it wasn’t really a question of whether I would go to college, but what I would study. My parents wanted me to be an engineer. I majored in history. Once someone pointed out that a history degree was great for law school, they became keen. Of course, in the end, I became a professor rather than a lawyer. My parents have had to learn to live with that disappointment.”

During his undergraduate degree study at Murray State University, he was, he says, “able to thrive scholastically and intellectually while also engaging in escapades and behaviour of rather questionable judgement”.

Asked if he thinks degree study in the US should be free, as it is in, for example, Germany, Jobs observes: “The steady defunding of education in the US is having severely detrimental effects within and beyond higher education, including in the form of outrageous student debt. Lower tuition rates would be a very good thing, but only with a very significant investment of public funding throughout our educational system.”

As he is younger than the members of the baby boomer/1968 generation whose stories and era are a major part of his book, does Jobs believe his own experiences travelling in Europe would have been markedly different to theirs – and would he have wished to swap places with one of that cohort?

“I was a Eurailing backpacker in the summer of 1990, less than a year after the opening of the Berlin Wall,” he recalls. “It was a very exciting time to be traveling around, including behind the so-called Iron Curtain. The sense of momentous change was palpable. That summer is when I decided to pursue my doctorate in European history.”

In a digital age, do his own students have the same wanderlust?

“I think travel for them is a bit different. First of all, being on the West Coast, my students are much more oriented toward travel in Asia than I was; economically it isn’t as cheap as it once was, especially in Europe, but elsewhere too; and technologically, they aren’t adrift and apart in the same way as young people were before, as they remain interconnected through the hypermobility of telecommunications,” Jobs says. “Still, I think the quality of exploration afforded by being on one’s own in a foreign place retains its sense of adventure.”

Is there anything about his current institution that he would change if it were in his power?

Jobs replies: “Pacific is a hybrid university. We have a traditional small liberal arts college for undergraduates connected to graduate programmes concentrated in the health professions. The undergraduate faculty are committed to the liberal arts college model, but, as is the trend nationally, the institution is pushing us to move away from it. I would like to reverse that. Also, more days of sunshine.”

And what gives him hope?

“I’m surrounded by thoughtful, smart, hard-working people – my spouse, my children, my family, my friends, my students, my colleagues, my community.”

Karen Shook

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Trailblazers of a united continent

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?