As you fly into San Francisco International Airport, the plane banks sharply over the southern extremity of the Bay Area. Looking down, the grey blur of gridded concrete neighbourhoods dissected by freeways makes up the group of cities known collectively as Silicon Valley. Compared with the vibrant variety of landscape and architecture in San Francisco, 40 miles to the north, it doesn’t look like much – but walk along these streets with your ears open and you start to hear indications of what has made this zone of technological innovation so iconic. If you spend a few days in the diners of Mountain View, over hotel breakfasts in Palo Alto or Sunnyvale and in the venture capital lunch spots of Menlo Park, you can overhear dozens of fascinating business pitches – and speculate on which will be funded and become the next Big Thing.

Cade Metz clearly knows these streets well, since Genius Makers provides an extraordinarily rich picture of the people and places of Silicon Valley. He stylishly recounts pivotal episodes that have contributed to the industrial-scale development of artificial intelligence here over the past couple of decades. A reporter rather than an academic, he has built this valuable social and technological history on a profoundly useful series of interviews, meetings and conversations, capturing a series of tech developments that might inform the future role and structure of the industry. Working from the San Francisco bureau of The New York Times, and as a resident of the Bay Area, Metz has had a seat in the front row as a handful of huge tech companies have fought keenly to make artificial intelligence a core part of their portfolios.

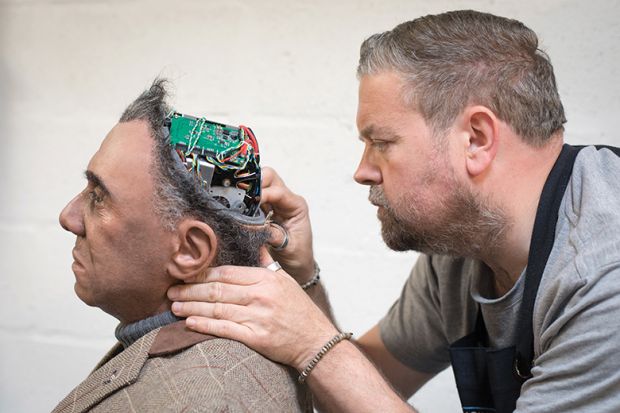

The book presents the history of AI from its inception in the late 1950s, with the experiments of Marvin Minsky and Frank Rosenblatt, to the current era. It is a field that has had many false dawns and a number of abrupt reversals of fortune but still appears to have so much promise that, throughout the latter half of the 20th century, people kept coming back to it. Slowly, mostly through incremental change but with the occasional lightning stroke of innovation, the industry has developed abilities that might soon approach the Holy Grail of Artificial General Intelligence, meaning that an artificial entity could operate successfully and reliably in a real-world environment.

Many of the basic historical aspects of artificial intelligence development have already been well rehearsed elsewhere, but this book scores in the range of material gleaned from folks who were actually in the room at key moments over the past two decades – through more than 400 interviews carried out over a period of eight years. Given the blisteringly fast pace of change in this industry, I suspect that future academic researchers will view this primary source material as a seam of pure gold.

The treatment of the story is thematic, rather than strictly chronological, which well suits the extremely complex nature of the interrelations between people, places and events. This complexity is reinforced by the addition of both a useful timeline and a detailed list of the “Players” in a story that, at times, feels more like a Tolstoy novel than a technical narrative – and I mean that in a good way. Looking down the list of characters, I realised that I had met and interviewed at least four of them myself, allowing me to test how they are presented in this book with a degree of confidence. Happily, I recognised both the characters and their traits, which suggests to me that the wider narrative is likely to be equally accurate.

From the viewpoint of academia, this book provides some interesting angles because it details how the big tech companies have sought to bring unique academic expertise into their organisations. It should come as no surprise that there have been offers of eye-watering sums of money to specific research leaders – sums that might make some readers look back at their own career choices with pursed lips.

The process of specialist recruitment often features subtle approaches at conferences, hotel meals, low-key rural retreats and a degree of confidentiality that approaches paranoia. On one typical occasion, the target individual, instead of simply taking the train back from a conference, was spirited across the Atlantic by private jet to hold meetings with potential collaborators, only to be delivered home at the same time as the train arrived.

The text focuses on the notion of “mavericks” as key players in the development of artificial intelligence – and there have undoubtedly been a few of these. Yet a number of major innovators have opted not to leave the academy when approached by the big tech companies – and have used the power of their marketability to negotiate their own terms. One symptom of this is the growth of well-funded outposts of Silicon Valley close to academic centres around the world. This reflects how the tech companies have worked to become truly global in the past decade. But it also offers a chip in the game to those who don’t desire the high-pressure lifestyle of northern California if it means losing their relationship with their chosen community – and indeed their local research team.

Metz doesn’t pull his punches when discussing some of the recent, highly publicised, issues around the negative potential of artificial intelligence systems – such as enabling election manipulation and powering the pseudo-reality of deepfake images, not to mention the startling exposure of inherently racist traits in some products. He sets out clearly the mechanisms through which these problems have arisen, and the approaches industry and society as a whole need to take to address them.

The interest of the military in the development of autonomous weapon systems is another of the worries the author highlights. As relationships with the defence industry become closer, some tech companies that formerly espoused a firm ethical stance have seen public perception of their loyalty to such principles slip. While some projects might be stalled by those who decline to work in this environment, it appears unlikely that the direction of travel can be altered solely by individual action.

The story of the road towards true artificial intelligence is far from over – and the ethics-based concerns about some big tech companies clearly illustrate just how much is at stake for society. I hope that Cade Metz is already working on the sequel to this, his first book. As an author with a firm grip on his field, he makes a knowledgeable guide to the intriguing corners of Silicon Valley and beyond.

John Gilbey teaches in the department of computer science at Aberystwyth University.

Genius Makers: The Mavericks Who Brought AI to Google, Facebook, and the World

By Cade Metz

Random House Business, 384pp, £20.00

ISBN 9781847942135

Published 18 March 2021

The author

Cade Metz, a technology correspondent with The New York Times, was born in Raleigh, North Carolina, where his father was an engineer and programmer with IBM. As a result, he says, he “grew up on stories” about the development of “the barcode now used to scan groceries across the globe”, including “the protests mounted outside grocery stores when the technology was first installed in checkout lines. Some saw the barcode as ‘the sign of the beast’ that foretold the end of the world in the New Testament. This was a (rather colourful) lesson that new technology could raise fear as well as hope.”

Like his parents, Metz studied at nearby Duke University, majoring in English but also taking courses in computer science. This led him into a career as a journalist specialising in technology, initially as a researcher and fact-checker at PC Magazine. It was after securing a writing job at Wired magazine in San Francisco, he recalls, that he “began covering the rise of what is called artificial intelligence and first discovered the characters at the heart of my book”.

Asked why ordinary citizens should be interested in (and perhaps concerned about) the progress of research in AI, Metz replies that the technology is “increasingly prevalent in our daily lives, from digital assistants like Siri to online ‘chatbots’ that can carry on a conversation to the facial recognition services and other surveillance technologies that are moving into police departments and other government agencies across the globe”.

Although “AI can make our lives easier”, Metz goes on, there is room for real concern about, for example, “a new breed of autonomous weapons” and technologies that “can be biased against women and people of colour”. Equally alarming were the possibilities for “miscreants to generate disinformation and spread it online, [using] photos and videos as well as tweets, blog posts and articles that look like the real thing but are actually designed to deceive”.

Matthew Reisz

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Apostles of next-level thinking

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?