This is a marvellous book, an original contribution to our understanding of how plaster casts of sculpture and architectural elements were manufactured and displayed in museums throughout Europe and America, which makes important points concerning their cultural, political, educational and philosophical significance.

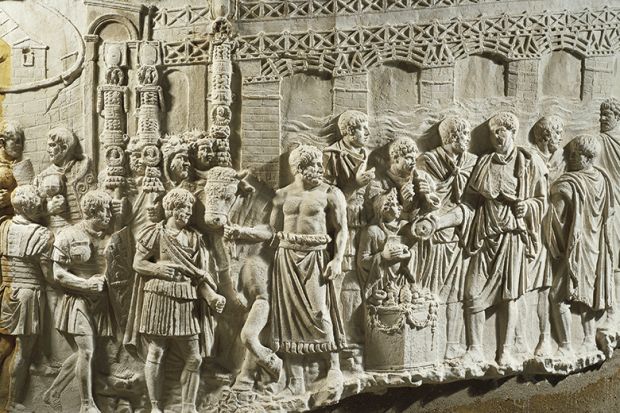

Many casts of ancient sculptures, for example, when compared with the originals from which they had been taken many years earlier, were not eroded by pollution or otherwise damaged, and so acquired lives and values of their own. When travel to see real works of art and architecture was not possible for large numbers of ordinary people, the exhibits, showing parts of Greek, Roman, medieval and other buildings, familiarised whole generations with ancient temples, portals, sculptured figures, decorations, the Classical Orders of architecture and much else. Some of the most spectacular collections were held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the École des Beaux-Arts, Paris, and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, but there were others, in many places, including Brussels, the Crystal Palace, Sydenham and Sir John Soane’s Museum, London.

In rather too many instances (the Soane Museum is an honourable exception), those great collections of plaster casts have been destroyed, or consigned to warehouses where their decay is assured, and so they, like the originals from which they were taken (some of which no longer exist), face oblivion. Influenced by French exemplars in the 19th century, the Yale School of Fine Arts acquired a superb assortment of casts, but in 1950 the new chairman of the department of design at Yale, Josef Albers, fired with the attitudes of what architectural historian Osbert Lancaster described as “Bauhaus balls”, dumped the collection, some of which was reused by Paul Rudolph in his Brutalist Art and Architecture building at Yale (which burned down in 1969). Albers, like other Bauhäusler, did not like nudes, insisting that models pose in their underwear. When it was suggested to him that this might be regarded as more erotic than if they were naked, Mari Lending reports that he “just didn’t get it”. Eroticism, like beauty, was banished from that arid, humourless, desiccated world.

Lending’s superbly illustrated book induces feelings of helpless rage when considering the terrible losses inflicted not only by the Bauhäusler and their iconoclastic disciples, but also by the soixante-huitards in France, who contributed their fair share to the damage. The casts were not only wonderful things in themselves, but they had educational and aesthetic value, and took on temporalities of their own: they were records, exemplary, and part of a coherent and rich cultural narrative. Naturally, their survival was unacceptable to those who wanted the tabula rasa: compared with a poverty-stricken Modernism that could only boast a handful of dreary clichés instead of an expressive sophisticated language with an inexhaustible vocabulary, they had to go.

In 2015, Islamic State destroyed much of what remained at Palmyra, and an arch from there was digitally reconstructed and erected in Trafalgar Square, arousing public interest and prompting debates about the “morality” of reproducing such artefacts. The actions of people such as Albers were not that far removed from those of the Taliban, however: Walter Gropius, for example, supported the demolition (1964) of one of the greatest monuments of American Beaux-Arts Classicism, Pennsylvania Station, New York (designed by McKim, Mead, & White, 1906-10), a sublime masterpiece that showed up the aesthetic poverty of Bauhaus-approved architecture. And the whole ethos of forming collections of plaster casts for display was an essential part of Beaux-Arts education, so had to be obliterated, just as the real architecture of Pennsylvania Station was not permitted to survive.

Lending’s melancholy Proustian voyage of remembrance raises many issues of considerable import in these benighted times, but it is a pity that she and her publisher could not have provided a better index: this one is not really up to the job. Nevertheless, Plaster Monuments is a welcome addition to debates surrounding copies, reproductions, records and the history of civilisation itself.

James Stevens Curl’s Making Dystopia: The Strange Rise and Survival of Architectural Barbarism will be published by Oxford University Press in August.

Plaster Monuments: Architecture and the Power of Reproduction

By Mari Lending

Princeton University Press, 304pp, £41.95

ISBN 9780691177144

Published 10 November 2017

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: More than a chip off the old block

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?