Neglected, misplaced, forgotten, stolen – the fate of time capsules is hardly illustrious. Tens of thousands of these vessels, according to Nick Yablon, have been buried across the United States. Even when they fulfil their mission as “transtemporal” inscriptions, or timed messages, and reach their target date intact, their dubious contents are typically dispatched to a storage warehouse, a library basement, an inconspicuous display cabinet, or otherwise consigned uncatalogued to archival oblivion. Discarded in so many “sterile manila folders”, it is evidently not the contents of these vessels that merit serious attention. Yablon himself is not averse to compiling exhaustive lists, but as Remembrance of Things Present ably demonstrates, it is the practice itself, the use of time capsules as mnemonic devices, that has potentially interesting things to tell us about the collective temporal imagination, but also about our more personal investments in the envisaged future.

Yablon meticulously reconstructs the history of what he calls the “time-vessel tradition”, spanning a 60-year period from its hesitant beginnings in the 1870s to the interwar years. No stone is left unturned in a historical narrative that suggests its author may have contracted something of the “frenzied spirit of completism” he attributes to the interwar vessels and their fantasies of “universal libraries”. Things tend to sag in places under the accumulated weight of so much factual information, not to mention almost 1,500 footnotes. But while compilation far outweighs critical analysis, a series of fascinating observations nonetheless emerges from the mass of empirical detail. It becomes increasingly evident as one follows the plot that the desire to communicate with the future through a sealed box raises interesting questions about intergenerational responsibility, the politics of memory, utopian thinking and secularised versions of hope and redemption. Particular attention is paid to our duty towards posterity, or the “quality of looking, with beneficent regard, far into the distant future”. And yet, as with most of the observations in this book, Yablon’s treatment of time vessels as an invention of the Gilded Age and the “crisis of posterity” in the late 19th century is suggestive rather than fully explored.

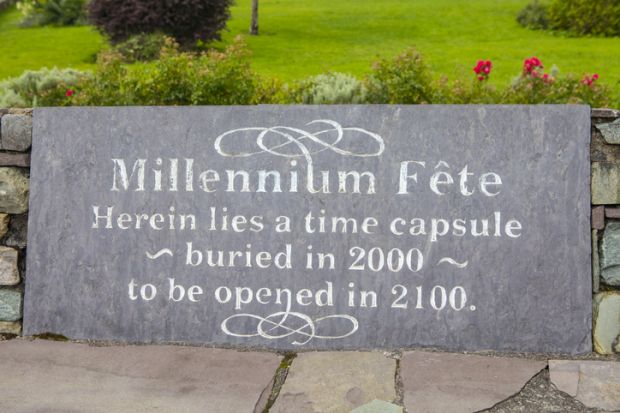

When the author adopts a more discursive approach towards his material, things become far more animated, resulting in a series of engaging historical portraits of childless hopefuls investing in surrogate links to posterity. A San Francisco dentist with a Pharaoh complex rubs shoulders with a Barbadian immigrant and civil rights lawyer, the only identifiable black contributor to the earlier vessels. And the narrative culminates with some intriguing reflections on the legacy of the time vessel tradition, with Yablon suggesting that the decline of the corporate variant introduced by the Westinghouse Time Capsule in the 1930s is countered by the resurgence of the self-commemorative impulse and the privatisation of the future. This is a reference to the generative impact of the internet on time vessels: futureme.org boasts more than 7 million letters posted to posterity. But the transience of digital memories is no less significant. I was left with the image of a child, possessed by elaborate fantasies of future generations, going out into the garden and burying something concrete in the ground, maybe a treasured toy.

Steven Groarke is professor of social thought at the University of Roehampton, and a psychoanalyst.

Remembrance of Things Present: The Invention of the Time Capsule

By Nick Yablon

University of Chicago Press

384pp, £34.00

ISBN 9780226574134

Published 18 June 2019

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Knick-knacks of the future past

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?