“He burst into tears.” That’s a compelling opening – he being the Prince Regent, who has just been told that his country is in a terrible state. I wished to know more about the weeping tendencies of the future George IV, especially since he is later said to have blubbered at criticism of the cut of his waistcoat. But the Regent is an oddly shadowy figure in this rattling study of his rule, or misrule, and the 10 years that count as the Regency (1811-20; as George IV, Britain was stuck with him until 1830). The deviser of enduring – and beautiful – designs, including the Royal Pavilion at Brighton and London’s Regent’s Park and Regent Street, George was viscerally despised. The caricaturist George Cruikshank, although careful to keep a foot in the pro camp, produced radical satires that “created an indelible impression of the Regent as a callous buffoon and inveterate sot”.

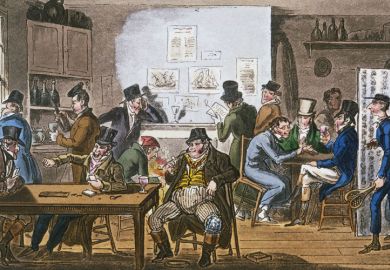

With such crisp phrasing, Robert Morrison creates an indelible impression of the Regency. It’s hectic, which is not always a good thing, although it packs in tons of social history, and is especially good on crime, prostitution and the simmering resentments of a people unrepresented, exploited, often starving and trampled over by the rich, now including industrialists. Political struggle is told through the likes of Leigh Hunt, Thomas Moore, William Hone and William Cobbett, in literary miniatures. Elizabeth Fry gets a walk-on part, as a reformer of the hellish prisons into which so many were cast. Emigration, transportation, empire and war soaked up other luckless lives, especially in North America, India and Australia, where Indigenous peoples were also uprooted or oppressed. A huge canvas is covered with great brio.

There’s no doubt that the Regency was a lively time, and in many ways Morrison catches it with spirited energy and pithy narrative. “Luddite” and “Waterloo” are still terms in common use, and with Peterloo recently in the spotlight, some sense of why we might want to keep these Regency phenomena alive feels important. The book does not encompass that, although the section on Waterloo explains Wellington’s strategy very readably, so you get a sense of how a great general thinks. His eponymous boots are not accounted for, although they really are an instance of the Regency making the modern world. Military discipline, key to Wellington’s command, had its curious counterpart in sartorial codes, so strict that Wellington himself was turned away from one club, Almack’s, for wearing the wrong sort of trousers (he went meekly).

Sandwiched between 18th-century rakery and Victorian repression, Regency libertinism seems perversely related to the politics of liberty that also ran through the period. Most fervently voiced by Percy Bysshe Shelley, who is amply quoted, the remit of liberty was the deepest of many arguments between rebels and reactionaries. As Morrison draws on many literary writers, is the label “Romantic” helpful? What do we gain by replacing it with “Regency”? Both the battles of ideas and the reign of appetites are staged, vivaciously: the book puts passion forward as a common denominator, although often in its lowest forms, such as cruelty, brutality and greed. After a rollicking chapter on sexual pastimes, Morrison observes sagely that there were still some happy marriages in this period. What he calls the Regency cacophony of attitudes to sex, which he thinks still shapes our own views, is a bigger cacophony of conflicting ideas about what makes a good society. Rich social history such as this describes discord; I don’t think it explains it.

One of Morrison’s consistent interests is in how people in the countryside suffered, whether from the effects of volcanic eruption from Mount Tambora, Indonesia in 1815, making a dismal summer with wretched harvests, or landlords’ greed, especially in Scotland, where profitable and uncomplaining sheep were brought in, turning tenants into impoverished emigrants. Bad weather, it’s hinted, also accounts for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. In the countryside, rural poverty was written about by John Clare, and painted out by John Constable. The Regency Revolution discusses them both, but divided by a section title that effectively keeps them apart. You might draw an inference from that separation, that the period was really divided and those differences resist being reconciled. Yet the clashes between sides, as at Peterloo (when the cavalry charged a crowd demanding parliamentary reform), speak to visions so profoundly opposed that British society almost tore itself apart. Doesn’t that have a contemporary ring?

The main weakness of this book is special pleading, or a repeated assertion that the Regency made the modern world. An instance of overreach: “Our society’s addiction to consumption – to buying stuff – took hold in the Regency.” This comes after an engaging paragraph about the kaleidoscope, invented by the Scottish physician David Brewster in 1816 and sold as a toy – but prefaced with another annoying claim: “The first craze for a novelty item belongs to the Regency…” Sellers of toy balloons in 1784 were certainly cashing in earlier. I was almost persuaded by the claim that the Regency invented recreational drug-taking, but then I remembered laughing gas, popularised by Thomas Beddoes and Humphry Davy via the Pneumatic Institution in Bristol, which got going in 1799 and promoted gas-induced hilarity alongside serious science.

Given that the book positions itself as the first history of the Regency for 30 years, it is a bit dismaying to see so many canonical names and so few more recently reclaimed. Anna Laetitia Barbauld, for instance, whose Eighteen Hundred and Eleven: A Poem (1812) foresaw the rise of America as an empire, is nowhere mentioned. But Jane Austen pops up regularly, as if she’d run round the back and rejoined the historical pageant. She would have been amused, no doubt, to head up the subtitle. The subtitle for the American edition – “Jane Austen Writes, Napoleon Fights, Byron Makes Love”, it begins – simply invites satire.

Among the many delightful illustrations is a sketch by Thomas Rowlandson of a women’s cricket match from 1811. I had to consult another social history of the Regency to discover that it was Surrey v Hampshire, and the teams were set up by aristocrats in both counties, for 500 guineas a side. After three days’ play, Hampshire won. Consulting an anthology of women’s cricket reveals that it was the very first women’s county match, and such a success that another was immediately arranged. It’s a small thing, perhaps – every social history has to have its limits – but symptomatic of this study’s preference for synthesising existing research, albeit very capably, to digging any deeper. One wonders about the men who paid for this match – who and why? And women’s cricket gets a famous mention when Jane Austen introduces the heroine of Northanger Abbey (completed in 1803, published in 1817): “It was not very wonderful that Catherine [Morland], who had nothing heroic about her, should prefer cricket, base-ball, riding on horseback, and running about the country at the age of fourteen, to books.”

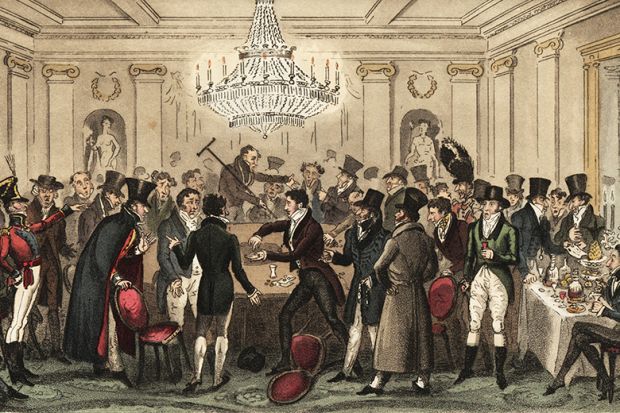

The cover image has no credit. It turns out to be a representation of the Duchess of Richmond’s famous ball on the eve of Waterloo, from which officers hurried to the fields of slaughter. It’s by Henry Nelson O’Neil, a Victorian artist of historical genre scenes. He painted it in 1868. In such accurate and fallacious ways, the Regency still fascinates us.

Clare Brant is professor of 18th-century literature and culture at King’s College London. Her most recent book is Balloon Madness: Flights of Imagination in Britain, 1783‑1786 (2017).

The Regency Revolution: Jane Austen, Napoleon, Lord Byron and the Making of the Modern World

By Robert Morrison

Atlantic

368pp, £20.00

ISBN 9781786491237

Published 4 July 2019

The author

Robert Morrison, who was recently appointed British Academy global professor at Bath Spa University, was born and raised in Lethbridge, southern Alberta, Canada, although he also recalls spending time in a family cabin in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. After a first degree at the University of Lethbridge, he went on to an MPhil at the University of Oxford and a PhD at the University of Edinburgh. His supervisors, he says, taught him to “push and push an idea until I had something worth saying. Geoffrey [Carnell in Edinburgh] would often say, ‘That’s interesting, Robert, but it doesn’t quite get off the ground.’ I have spent my entire career trying to make sure I get things off the ground.”

Given that his earlier books such as The English Opium-Eater: A Biography of Thomas De Quincey (2009) had a much narrower focus, what was it like for Morrison to try to produce an overview of a whole era? “A challenge!” he replies. “But what I enjoyed most was learning how much I didn’t know…I remember rereading Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park and being dumbfounded when I came across a reference to the War of 1812…In other instances, it meant examining someone who was prominent in the Regency but has since been neglected, such as the sportswriter Pierce Egan, the novelist Mary Brunton or the actress Dorothy Jordan.”

Asked about contemporary parallels with the Regency, Morrison points to “debates over freedom of the press, the steep downsidesof fame, our fascination with technology or the current opioid crisis”. Although the period makes clear that “some difficult transitions do come to an end, and ultimately prove beneficial”, it also shows that “protest and indignation are crucial if we are to come through these transitions with more people living better lives”.

Matthew Reisz

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: A discordant and decadent decade

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?